BitVM

A Last Resort: Un'FE'd Covenants For Bitcoin

Published

3 months agoon

By

admin

Jeremy Rubin released a proposal two weeks ago titled Un’FE’d Covenants (FE = Functional Encryption). Given the ongoing debate over covenant proposals for Bitcoin the last year or two, his proposal marks a new practical option. All covenant proposals so far require a soft fork (actual opcodes), the development and implementation of unproven cryptography (Functional Encryption), or an absurdly high monetary cost to use (ColliderScript).

Jeremy’s proposal requires no softforks, and does not impose a burdensome and impractical cost on users to utilize. The trade off for that capability is a radically different security model. By using a system of oracles, and BitVM based bonds capable of slashing, covenants can be emulated on Bitcoin right now.

The Oracles

The first part of the scheme is obviously the oracles that enforce different covenant conditions. This is a relatively straightforward set up, and the first building block necessary for Jeremy’s proposal. The oracle has custody of the funds in this scheme, and is entrusted with the enforcement of the covenant conditions. You want the oracle to not have to locally keep track of the covenant conditions being enforced for each coin it custodies. This introduces state risk where if the oracles database is corrupted or lost it has no idea how to handle honest enforcement for everyone’s coins. In order to get around this problem, Jeremy makes use of Taproot.

Schnorr based keys can be “tweaked” by using the hash of data to modify a public key. This enables the tweaking of the corresponding private key to be able to sign for the modified key, as well as prove that whatever data was used to tweak the public key is committed to by that key. Having the oracle generate a key, and then the user tweaking that key with their covenant program allows a commitment to what the oracle is supposed to enforce while keeping the burden of storing that information on the user.

Oracles can also be federated in order to minimize the trust required in a single party to enforce things. From here, users can simply load the resulting address, and whenever they want to enforce the condition, approach the oracle(s) with the spending transaction, the oracle program, and the witness data necessary to prove that the transaction given to the oracle meets the conditions of the covenant. If the transaction is valid according to the covenant rules, the oracle signs it.

For any simple covenant where the outcomes are known ahead of time, such as CHECKTEMPLATEVERIFY (CTV), users can immediately have the oracle pre-sign the transactions enforcing the covenant and simply delay using them until necessary.

An important scenario to consider requiring extra functionality is state based covenants, such as rollups, that progress regularly and have an actual state (the current balance of users) to keep track of. In the case of such covenants, the transactions the oracle signs must commit to the current state of the covenant using OP_RETURN so that the oracle can efficiently verify each transaction updating the rollup or other system without having to download witness data for the entire history. This is to keep the oracle from having to store state locally themselves, which as noted above creates risks.

In the long term the data requirements of oracles can be optimized by using zero knowledge proofs, so that the oracle can simply verify a proof that the transaction they are being asked to sign follows the rules of the covenant without having to verify the raw witness data for larger more complex covenants. Again though, in the case of systems like rollups, care must be taken in designing them to guarantee that data required to exit the system is made available to users so they have it in their possession if they need to contact the oracle directly to reclaim their funds.

The BitVM Bond

So far the scheme is entirely trusted. You are essentially just giving someone else your money and hoping they can be trusted to enforce the conditions of arbitrary covenants. By modifying the scheme above slightly, this can be secured with a crypto-economic incentive rather than pure trust.

Above it was described how OP_RETURN is required to be used to track state for stateful covenants. OP_RETURN can also be used to publish the witness data of any covenant transactions to prove the conditions were correctly fulfilled.

A BitVM circuit can be constructed to verify whether a transaction signed by the oracle successfully matches the conditions of the covenant it is enforcing. Remember that the key itself that is generated and funds sent to commits to the conditions of any covenant being enforced. Meaning that data, as well as a transaction being spent from the address, can be fed into a BitVM instance.

Oracles can then be required to post a collateral bond with a BitVM operator (who must also post a bond for the Oracle to claim if they are falsely accused). This way, as long as the bond value is greater than the value secured in covenants by an oracle, the system can be securely used. There would be no way for an oracle to violate the conditions of a covenant they are enforcing without losing money in aggregate.

Trade Offs

There are clear trade offs here that are materially worse than simply implementing covenants in consensus rules. Firstly, the oracle must be online and reachable in order to make use of oracle enforced covenants. With the exception of pre-signed covenants such as CTV, if the oracle is offline when users need to enforce a covenant, they can’t. The oracle must be present to sign.

Secondly, the liquidity requirements for oracle bonds can become massive if the system was ever widely adopted. This makes it unbelievably inefficient compared to native implementation of covenant opcodes at the consensus level.

Lastly, the extra data required to be posted on-chain in order for the BitVM bond scheme to work is much less efficient with use of blockspace than native covenant implementations.

Overall, the proposal is nowhere near as efficient and secure as native covenants. On the other hand, if we do wind up in the worst case scenario of pre-mature ossification, this is a very workable way to shoehorn covenants into Bitcoin without depending on unproven cryptography or completely impractical costs imposed on end users.

Jeremy has given us a worst case scenario option to expand the design space of what can be built on Bitcoin.

Source link

You may like

Can a Meme Coin Fund the Future of Scientific Research?

Analyst Confirms XRP Price Is Still On Path To $130

Proof-of-Work Crypto Mining Doesn’t Trigger Securities Laws, SEC Says

Crypto campaign donations are democracy at work — former Kraken exec

1 Million Bitcoin In New Whale Hands—A Mega BTC Rally On The Horizon?

Argentina’s Senate Hosts First-Ever Conference On Bitcoin Regulation

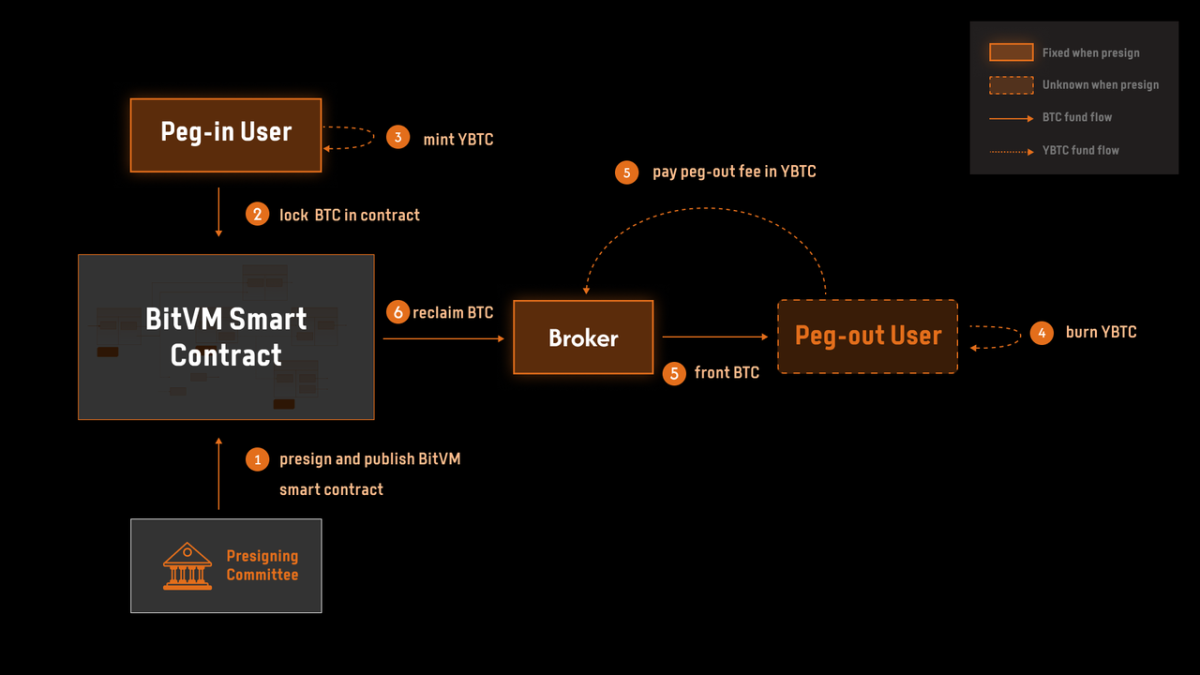

The introduction of BitVM smart contracts has marked a significant milestone in the path for scalability and programmability of Bitcoin. Rooted in the original BitVM protocol, Bitlayer’s Finality Bridge introduces the first version of the protocol live on testnet, which is a good starting point for realizing the promises of the Bitcoin Renaissance or “Season 2”.

Unlike earlier BTC bridges that often required reliance on centralized entities or questionable trust assumptions, the Finality Bridge leverages a blend of BitVM smart contracts, fraud proofs, and zero-knowledge proofs. This combination not only enhances security but also significantly reduces the need for trust in third parties. We’re not at the trustless level that Lightning provides, but this is a million times better than current sidechains designs claiming to be Bitcoin Layers 2s (in addition to significantly increasing the design space for Bitcoin applications).

The system operates on a principle where funds are securely locked in addresses governed by a BitVM smart contract, functioning under the premise that at least one participant in the system will act honestly. This setup inherently reduces the trust requirements but has to introduce additional complexities that Bitlayer aims to manage with this version of the bridge.

The Mechanics of Trust

In practical terms, when Bitcoin is locked into the BitVM smart contract through the Finality Bridge, users are issued YBTC – a token that maintains a strict 1:1 peg with Bitcoin. This peg is not just a promise but is enforced by the underlying smart contract logic, ensuring that each YBTC represents a real, locked Bitcoin on the main chain (no fake “restacked” BTC metrics). This mechanism allows users to participate in DeFi activities like lending, borrowing, and yield farming within the Bitlayer ecosystem without compromising on the security and settlement assurances that Bitcoin provides.

While some in the community might find these activities objectionable, this type of architecture allows users to get some guarantees that they previously could not hope to get with traditional sidechain designs, with the added bonus that we do not need to “change” Bitcoin to make it happen (although covenants would make this bridge design completely “trust-minimized, which would effectively make it a “True” Bitcoin Layer 2). For more details about the different levels of risks associated with sidechains designs, take a look at Bitcoin Layers assessment of Bitlayer here.

However, until such advancements come to fruition, the Bitlayer Finality Bridge serves as the best realization of the BitVM 2 paradigm. It’s a testament to what’s possible after the dev “brain drain” from centralized chains back to Bitcoin. Despite all the challenges that BitVM chains will face, I remain exceptionally excited at the prospect of Bitcoin fulfilling its destiny as the Ultimate Settlement Chain for all economic activity.

This article is a Take. Opinions expressed are entirely the author’s and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.

Guillaume’s articles in particular may discuss topics or companies that are part of his firm’s investment portfolio (UTXO Management). The views expressed are solely his own and do not represent the opinions of his employer or its affiliates. He’s receiving no financial compensation for these Takes. Readers should not consider this content as financial advice or an endorsement of any particular company or investment. Always do your own research before making financial decisions.

Source link

BitVM earlier this year came under fire due to the large liquidity requirements necessary in order for a rollup (or other system operator) to process withdrawals for the two way peg mechanisms being built using the BitVM design. Galaxy, an investor in Citrea, has performed an economic analysis looking at their assumptions regarding economic conditions necessary to make a BitVM based two way peg a sustainable operation.

For those unfamiliar, pegging into a BitVM system requires the operators to take custody of user funds in an n-of-n multisig, creating a set of pre-signed transactions allowing the operator facilitating withdrawals to claim funds back after a challenge period. The user is then issued backed tokens on the rollup or other second layer system.

Pegouts are slightly more complicated. The user must burn their funds on the second layer system, and then craft a Partially Signed Bitcoin Transaction (PSBT) paying them funds back out on the mainchain, minus a fee to the operator processing withdrawals. They can keep crafting new PSBTs paying the operator higher fees until the operator accepts. At this point the operator will take their own liquidity and pay out the user’s withdrawal.

The operator can then, after having processed withdrawals adding up to a deposited UTXO, initiate the withdrawal out of the BitVM system to make themselves whole. This includes a challenge-response period to protect against fraud, which Galaxy models as a 14 day window. During this time period anyone who can construct a fraud proof showing that the operator did not honestly honor the withdrawals of all users in that epoch can initiate the challenge. If the operator cannot produce a proof they correctly processed all withdrawals, then the connector input (a special transaction input that is required to use their pre-signed transactions) the operator uses to claim their funds back can be burned, locking them out of the ability to recuperate their funds.

Now that we’ve gotten through a mechanism refresher, let’s look at what Galaxy modeled: the economic viability of operating such a peg.

There are a number of variables that must be considered when looking at whether this system can be operated profitably. Transaction fees, amount of liquidity available, but most importantly the opportunity cost of devoting capital to processing withdrawals from a BitVM peg. This last one is of critical importance in being able to source liquidity to manage the peg in the first place. If liquidity providers (LPs) can earn more money doing something else with their money, then they are essentially losing money by using their capital to operate a BitVM system.

All of these factors have to be covered, profitably, by the aggregate of fees users will pay to peg out of the system for it to make sense to operate. I.e. to generate a profit. The two references for competing interest rates Galaxy looked at were Aave, a DeFi protocol operating on Ethereum, and OTC markets in Bitcoin.

Aave at the time of their report earned lenders approximately 1% interest on WBTC (Wrapped Bitcoin pegged into Ethereum) lent out. OTC lending on the other hand had rates as high as 7.6% compared to Aave. This shows a stark difference between the expected return on capital between DeFi users and institutional investors. Users of a BitVM system must generate revenue in excess of these interest rates in order to attract capital to the peg from these other systems.

By Galaxy’s projections, as long as LPs are targeting a 10% Annual Percentage Yield (APY), that should cost individual users -0.38% in a peg out transaction. The only wildcard variable, so to say, is the transaction fees that the operator has to pay during high fee environments. The users funds are already reclaimed using the operators liquidity instantly after initiating the pegout, while the operator has to wait the two week challenge period in order to claim back the fronted liquidity.

If fees were to spike in the meanwhile, this would eat into the operators profit margins when they eventually claim their funds back from the BitVM peg. However, in theory operators could simply wait until fees subside to initiate the challenge period and claim their funds back.

Overall the viability of a BitVM peg comes down to being able to generate a high enough yield on liquidity used to process withdrawals to attract the needed capital. To attract more institutional capital, these yields must be higher in order to compete with OTC markets.

The full Galaxy report can be read here.

Source link

Can a Meme Coin Fund the Future of Scientific Research?

Analyst Confirms XRP Price Is Still On Path To $130

Proof-of-Work Crypto Mining Doesn’t Trigger Securities Laws, SEC Says

Crypto campaign donations are democracy at work — former Kraken exec

1 Million Bitcoin In New Whale Hands—A Mega BTC Rally On The Horizon?

Argentina’s Senate Hosts First-Ever Conference On Bitcoin Regulation

Justin Sun Stakes $100,000,000 Worth of Ethereum Amid Calls for ‘Tron Meme Season’

Cardano wallet Lace adds Bitcoin support

Donald Trump Vows to Make America the ‘Undisputed Bitcoin Superpower’

Will Trump Announce Zero Tax Gains in Today’s Crypto Summit Talk?

Avalanche (AVAX) Drops 4.5%, Leading Index Lower

Tether’s US treasury holdings surpass Canada, Taiwan, ranks 7th globally

Here’s Where Support & Resistance Lies For Solana, Based On On-Chain Data

President Trump To Address The Digital Assets Summit Tomorrow

Analyst Says Bitcoin Primed for ‘Party Time’ if BTC Breaks Above Critical Level, Updates Outlook on Chainlink

Arthur Hayes, Murad’s Prediction For Meme Coins, AI & DeFi Coins For 2025

Expert Sees Bitcoin Dipping To $50K While Bullish Signs Persist

Aptos Leverages Chainlink To Enhance Scalability and Data Access

Bitcoin Could Rally to $80,000 on the Eve of US Elections

Sonic Now ‘Golden Standard’ of Layer-2s After Scaling Transactions to 16,000+ per Second, Says Andre Cronje

Institutional Investors Go All In on Crypto as 57% Plan to Boost Allocations as Bull Run Heats Up, Sygnum Survey Reveals

Crypto’s Big Trump Gamble Is Risky

Ripple-SEC Case Ends, But These 3 Rivals Could Jump 500x

Has The Bitcoin Price Already Peaked?

A16z-backed Espresso announces mainnet launch of core product

Xmas Altcoin Rally Insights by BNM Agent I

Blockchain groups challenge new broker reporting rule

Trump’s Coin Is About As Revolutionary As OneCoin

The Future of Bitcoin: Scaling, Institutional Adoption, and Strategic Reserves with Rich Rines

Is $200,000 a Realistic Bitcoin Price Target for This Cycle?

Trending

24/7 Cryptocurrency News4 months ago

24/7 Cryptocurrency News4 months agoArthur Hayes, Murad’s Prediction For Meme Coins, AI & DeFi Coins For 2025

Bitcoin2 months ago

Bitcoin2 months agoExpert Sees Bitcoin Dipping To $50K While Bullish Signs Persist

24/7 Cryptocurrency News2 months ago

24/7 Cryptocurrency News2 months agoAptos Leverages Chainlink To Enhance Scalability and Data Access

Bitcoin5 months ago

Bitcoin5 months agoBitcoin Could Rally to $80,000 on the Eve of US Elections

Altcoins2 months ago

Altcoins2 months agoSonic Now ‘Golden Standard’ of Layer-2s After Scaling Transactions to 16,000+ per Second, Says Andre Cronje

Bitcoin4 months ago

Bitcoin4 months agoInstitutional Investors Go All In on Crypto as 57% Plan to Boost Allocations as Bull Run Heats Up, Sygnum Survey Reveals

Opinion5 months ago

Opinion5 months agoCrypto’s Big Trump Gamble Is Risky

Price analysis5 months ago

Price analysis5 months agoRipple-SEC Case Ends, But These 3 Rivals Could Jump 500x