Bitcoin mining

Luxor’s Aaron Foster on Bitcoin Mining’s Growing Sophistication

Published

4 days agoon

By

admin

Luxor Technology wants to make bitcoin mining easier. That’s why the firm has rolled out a panoply of products (mining pools, hashrate derivatives, data analytics, ASIC brokerage) to help bitcoin miners, large and small, develop their operations.

Aaron Forster, the company’s director of business development, joined in October 2021, and has seen the team grow from roughly 15 to 85 people in the span of three and a half years.

Forster worked a decade in the Canadian energy sector before coming to bitcoin mining, which is one of the reasons why he’ll be speaking about the future of mining in Canada and the U.S. at the BTC & Mining Summit at Consensus this year.

Follow full coverage of Consensus 2025 in Toronto May 14-16.

In the leadup to the event, Forster shared with CoinDesk his thoughts on bitcoin miners turning to artificial intelligence, the growing sophistication of the mining industry, and how Luxor’s products enable miners to hedge various forms of risk.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

CoinDesk: Mining pools allow miners to combine their computational resources to have higher chances of receiving bitcoin block rewards. Can you explain to us how Luxor’s mining pools work?

Aaron Forster: Mining pools are basically aggregators that reduce the variance of solo mining. When you look at solo mining, it’s very lottery-esque, meaning that you could be plugging your machines in and you might hit block rewards tomorrow — or you might hit it 100 years from now. But you’re still paying for energy during that time. At a small scale, it’s not a big deal, as you scale that up and create a business around it.

The most common kind of mining pool is PPLNS, which means Pay-Per-Last-N-Shares. Basically, that means the miner does not get paid unless that mining pool hits the block. That’s also due to luck variance, so it’s no different from that solo miner’s situation. However, that creates revenue volatility for those large industrial miners.

So we’re seeing the emergence of what we call Full-Pay-Per-Share, or FPPS, and that’s Luxor is operating for our bitcoin pool. With FPPS, regardless of whether we find a block or not, we’re still paying our miners their revenue based on the number of shares they’ve submitted to the pool. That gives revenue certainty to miners, assuming hashprice stays the same. We’ve effectively become an insurance provider.

The problem is that you need a very deep and strong balance sheet to support that model, because while we’ve reduced the variance for miners, that risk is now put on us. So we need to plan for that. But it can be calculated over a long enough period of time. We have different partners in that regard, so that we don’t bear the full risk from our balance sheet.

Tell me about your ASIC brokerage business.

We’ve become one of the leading hardware suppliers on the secondary market. Primarily within North America, but we’ve shipped to 35+ countries. We deal with everybody from public companies to private companies, institutions to retail.

We’re primarily a broker, meaning we match buyer and seller, mostly on the secondary market. Sometimes we do interact with ASIC manufacturers, and in certain cases we do take principal positions, meaning we use money from our balance sheet to purchase ASICs and then resell them on the secondary market. But the majority of our volume comes from matching buyers and sellers.

Luxor also launched the first hashrate futures contracts.

We’re trying to push the Bitcoin mining space forward. We’re a hashrate marketplace, depending on how you look at our mining pools, and we wanted to take a big leap and take hashrate to the TradFi world.

We wanted to create a tool that allows investors to take a position on hashprice without effectively owning mining equipment. Hashprice is, you know, the hourly or daily revenue that miners get, and that fluctuates a lot. For some people it’s about hedging, for others it’s speculation. We’re creating a tool for miners to sell their hashrate forward and use it as a basic collateral or a way to finance growth.

We said, ‘Let’s allow miners to basically sell forward hashrate, receive bitcoin upfront, and then they can take that and do whatever they need to do with it, whether it’s purchase ASICs or expand their mining operations.’ It’s basically the collateralization of hashrate. So they’re obligated to send us X amount of hashrate per month for the length of the contract. Before that, they’ll receive a certain amount of bitcoin upfront.

There’s a market imbalance between buyers and sellers. We have a lot of buyers, meaning people and institutions wanting to earn yield on their bitcoin. What you’re lending your bitcoin at is effectively your interest rate. However, you could also look at it like you’re purchasing that hashrate at a discount. That’s important for institutions or folks that don’t want physical exposure to bitcoin mining, but want exposure to hash price or hashrate. They can do that synthetically through purchasing bitcoin and putting it into our market, effectively lending that out, earning a yield, and purchasing that hashrate at a discount.

What do you find most exciting about bitcoin mining at the moment?

The acceptance and natural progression of our industry into other markets. We can’t ignore the AI HPC transition. Instead of building these mega mines that are just massive buildings with power-dense bitcoin mining operations, you’re starting to see large miners turning into power infrastructure providers for artificial intelligence.

Using bitcoin mining as a stepping stone to a larger, more capital intensive industry like AI is exciting to me, because it kind of gives us a bit more acceptance, because we’re coming at it from a completely different angle. I think the biggest example is the Core Scientific / CoreWeave deal structure, how they’ve kind of merged those two businesses together. They’re complimentary to each other. And that’s really exciting.

When you look at our own product roadmap, we have no choice but to follow a similar roadmap to bitcoin miners. A lot of the products that we built for the mining industry are analogous to what is needed at a different level for AI. Mind you, it’s a lot simpler in our industry than in AI. We’re our first step into the HPC space, and it’s still very early days there.

Source link

You may like

Futureverse Acquires Candy Digital, Taps DC Comics and Netflix IP to Boost Metaverse Strategy

Court Grants Ripple And SEC’s Joint Motion To Suspend Appeal

AVAX Falls 2.1% as Nearly All Assets Trade Lower

What is a VTuber, and how do you become one in 2025?

Top Expert’s Update Sets $10 Target

How Academia Interacts With The Bitcoin Ecosystem

With all the current bearish sentiment and macroeconomic uncertainty swirling around both Bitcoin and the broader global economy, it might come as a surprise to see miners as bullish as ever. In this article, we’ll unpack the data that suggests Bitcoin miners are not just staying the course, they’re accelerating, doubling down at a time when many are pulling back. What exactly do they know that the broader market might be missing?

For a more in-depth look into this topic, check out a recent YouTube video here:

Why Bitcoin Miners Are Doubling Down Right Now

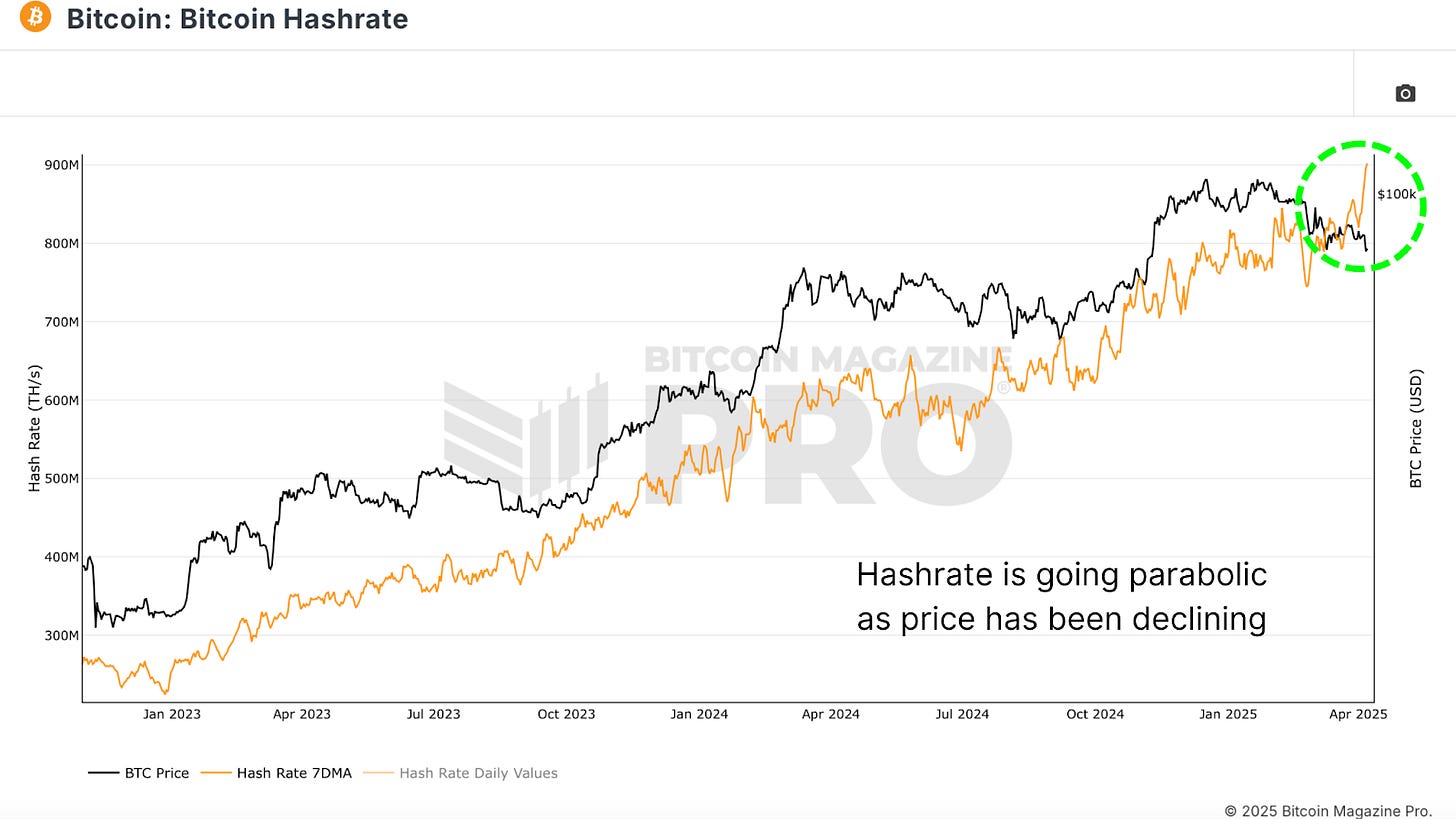

Bitcoin Hash Rate Going Parabolic

Despite Bitcoin’s recent price underperformance, the Bitcoin Hashrate has been going absolutely vertical, breaking all-time highs with seemingly no regard for macro headwinds or sluggish price action. Typically, hash rate is tightly correlated with BTC price; when price drops sharply or remains stagnant, hash rate tends to plateau or decline due to economic pressure on miners.

Yet now, in the face of heightened global tariffs, economic slowdown, and a consolidating BTC price, hash rate is accelerating. Historically, this level of divergence between hash rate and price has been rare and often significant.

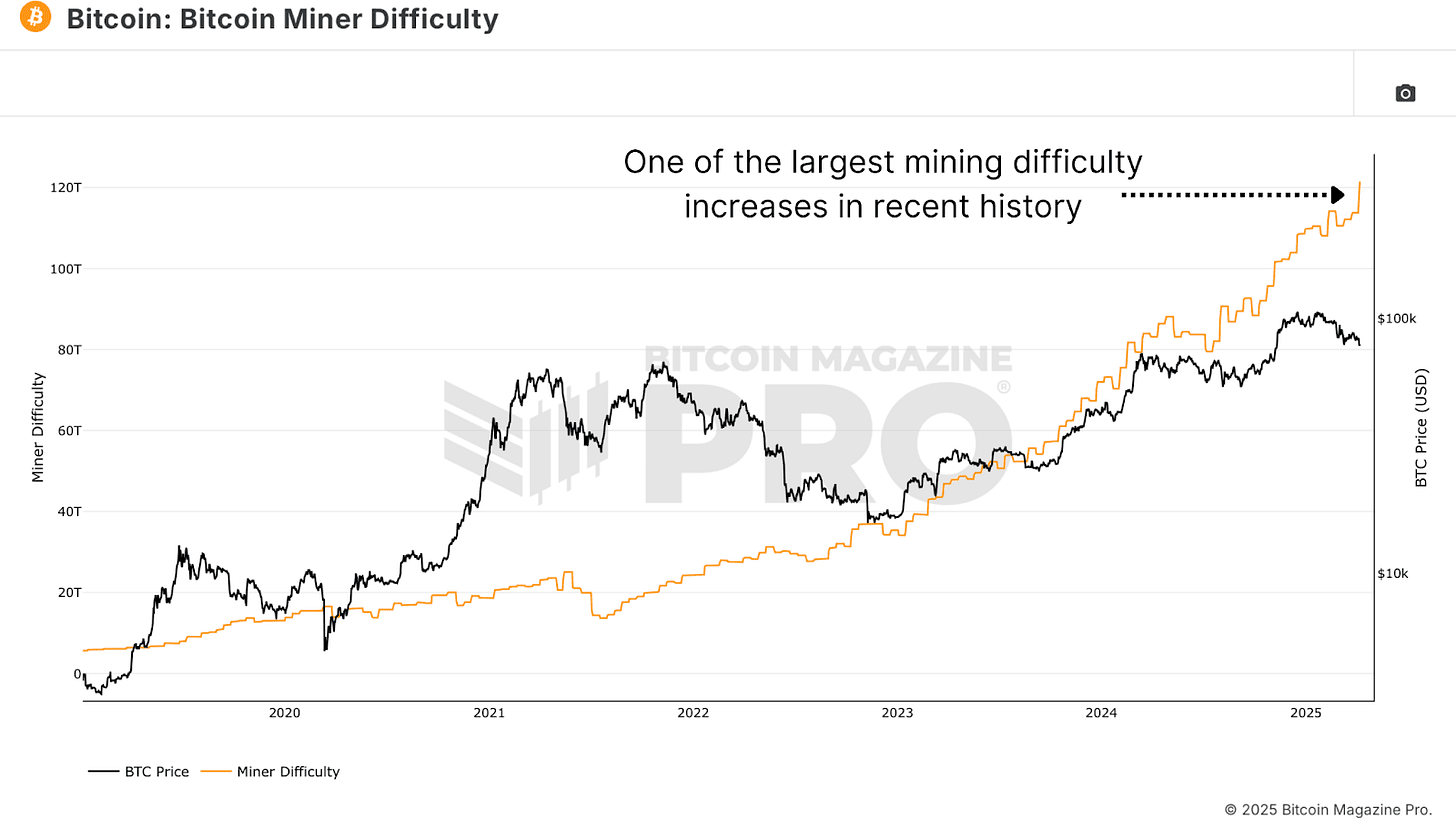

Bitcoin Miner Difficulty, a close cousin to hash rate, just saw one of its largest single adjustments upward in history. This metric, which auto-adjusts to keep Bitcoin’s block timing consistent, only increases when more computational power floods the network. A difficulty spike of this magnitude, especially when paired with poor price performance, is nearly unprecedented.

Again, this suggests that miners are investing heavily in infrastructure and resources, even when BTC price does not appear to support the decision in the short term.

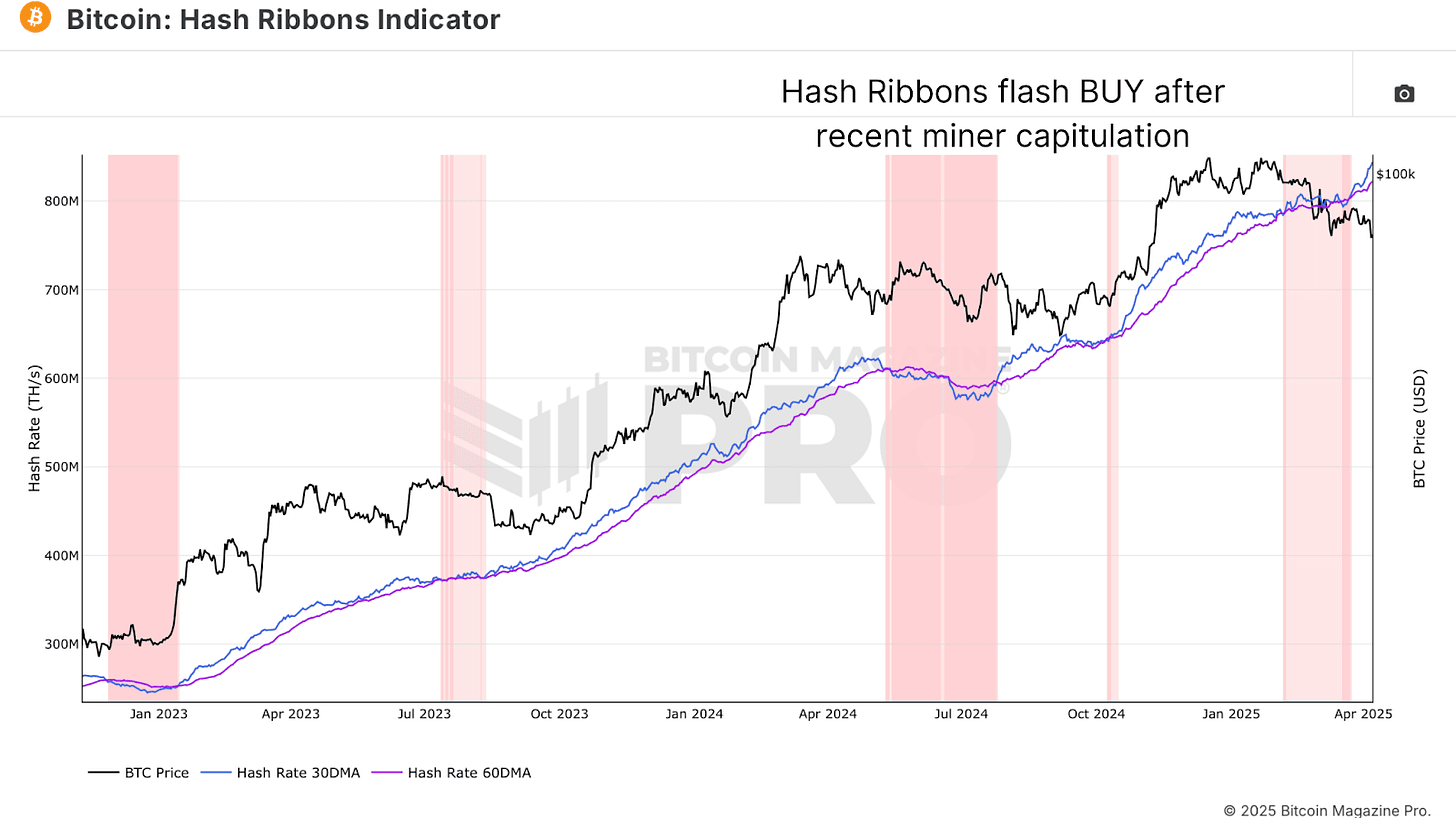

Adding further intrigue, the Hash Ribbons Indicator, a blend of short and long-term hash rate moving averages, recently flashed a classic Bitcoin buy signal.

When the 30-day moving average (blue line) crosses back above the 60-day (purple line), it signals the end of miner capitulation and the beginning of renewed miner strength. Visually, the background of the chart shifts from red to white when this crossover occurs. This has often marked powerful inflection points for BTC price.

What’s striking this time around is how aggressively the 30-day moving average is surging away from the 60-day. This is not just a modest recovery, it’s a statement from miners that they are betting heavily on the future.

The Tariff Factor

So, what’s fueling this miner frenzy? One plausible explanation is that miners, especially U.S.-based ones, are trying to front-run the impact of looming tariffs. Bitmain, the dominant producer of mining equipment, is now in the crosshairs of trade policies that could see equipment prices surge by 30–50%, potentially to even over 100%!

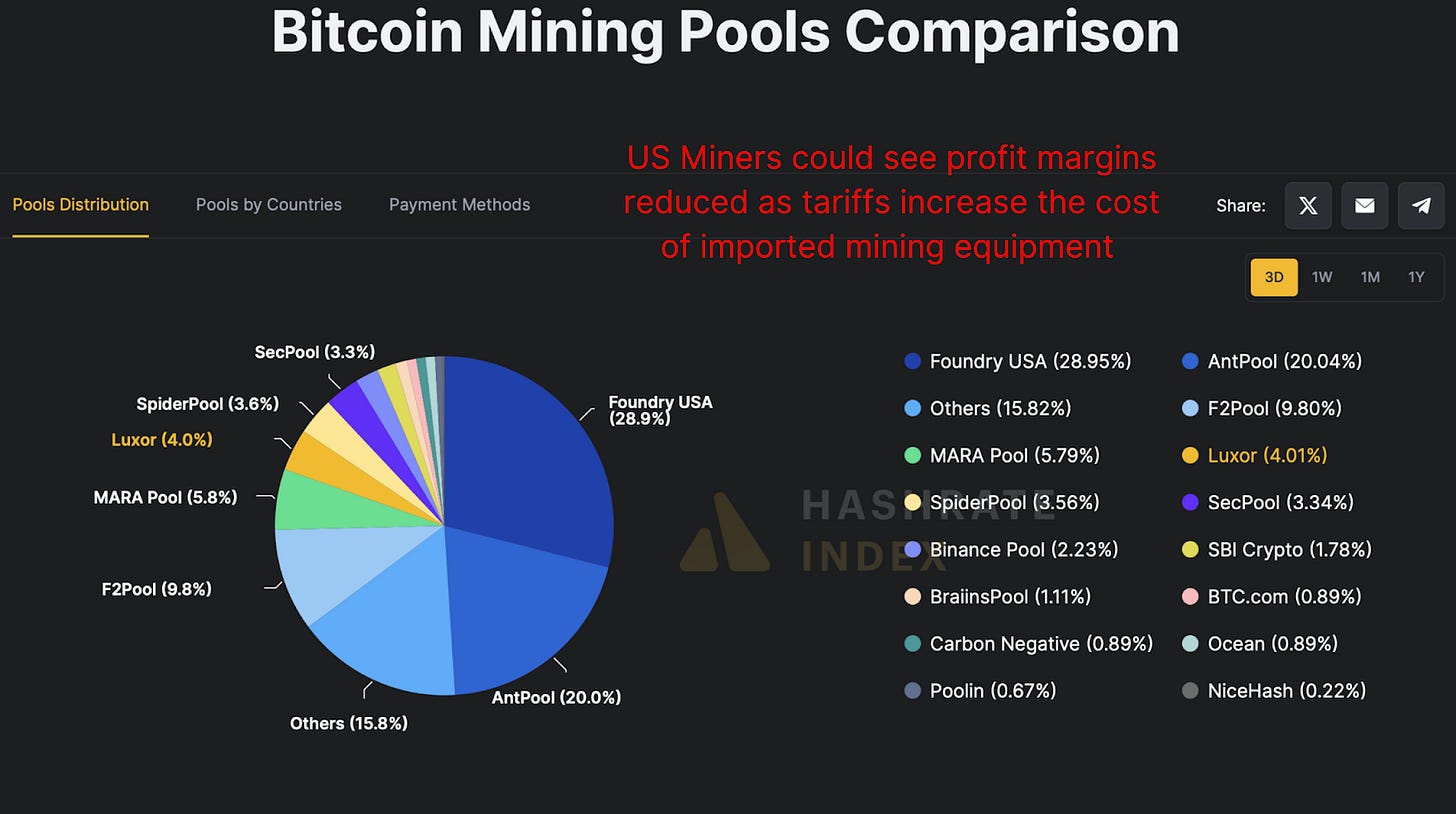

Given that over 40% of Bitcoin’s hash rate is controlled by U.S.-based pools like Foundry USA, Mara Pool, and Luxor, any cost increase would drastically reduce profit margins. Miners may be aggressively scaling now while hardware is still (relatively) cheap and available.

Bitcoin Miners Keep Mining

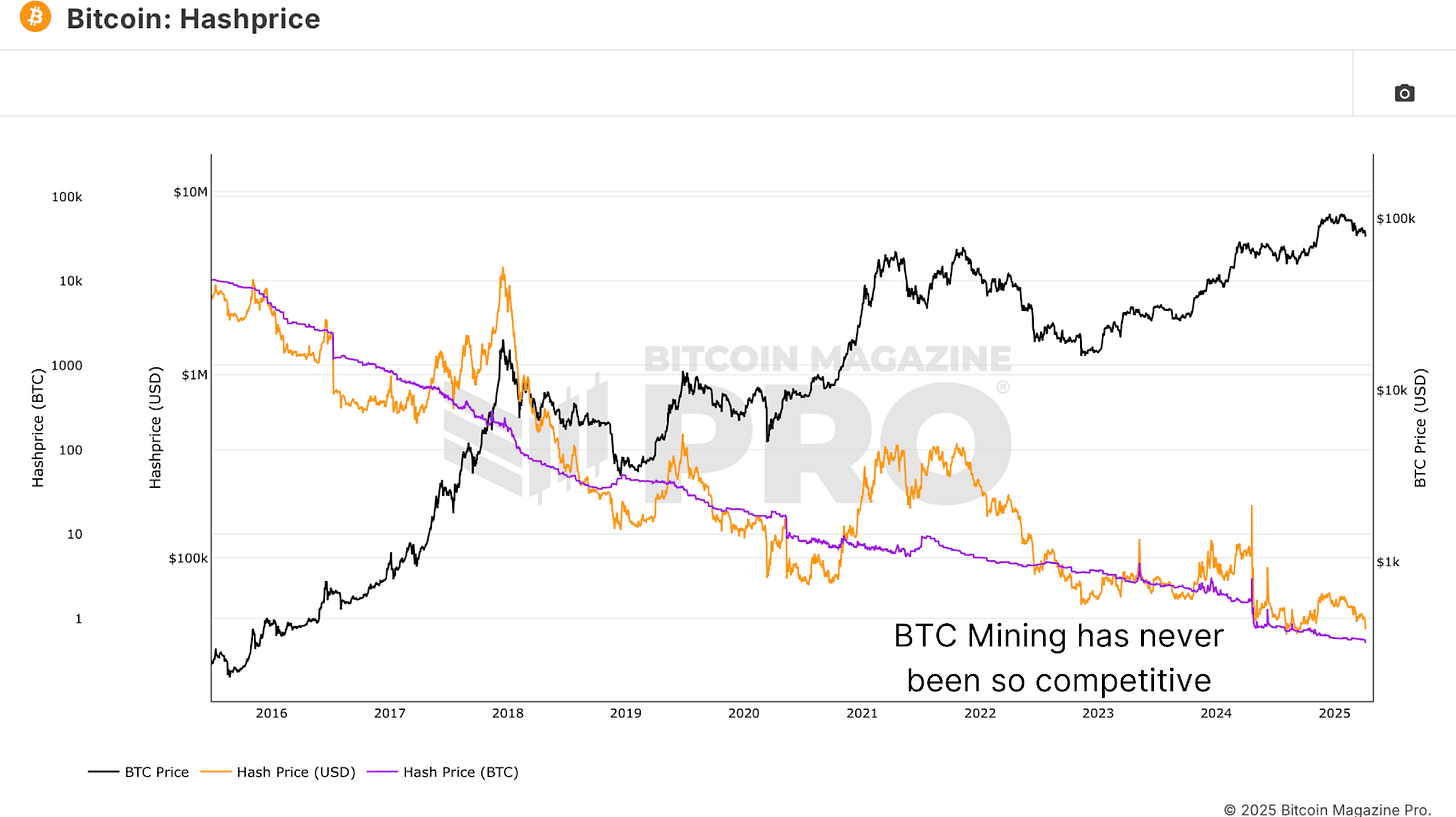

Hashprice, the BTC-denominated revenue per terahash of computational power, is at historical lows. In other words, it’s never been less profitable in BTC terms to operate a Bitcoin miner on a per-terahash basis. Typically, we see hash price increase toward the tail-end of bear markets, as competition fades and weaker players exit the space.

But that’s not happening here. Despite terrible profitability, miners are not only staying online, they’re deploying more hash power. This could imply one of two things; either miners are racing against deteriorating margins to front-load BTC accumulation, or, more optimistically, they have strong conviction in Bitcoin’s future profitability and are buying the dip aggressively.

Bitcoin Miners Conclusion

So, what’s really happening? Either miners are desperately front-running hardware costs, or, more likely, they’re signaling one of the strongest collective votes of confidence in the future of Bitcoin we’ve seen in recent memory. We’ll continue tracking these metrics in future updates to see whether this miner conviction is proven right.

If you’re interested in more in-depth analysis and real-time data, consider checking out Bitcoin Magazine Pro for valuable insights into the Bitcoin market.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and should not be considered financial advice. Always do your own research before making any investment decisions.

Source link

Bitcoin mining

The U.S. Tariff War With China Is Good For Bitcoin Mining

Published

6 days agoon

April 10, 2025By

admin

Today, China announced that it will increase tariffs on the goods it ships to the United States from 34% to 84% in response to President Trump stating that he will raise tariffs on the goods the U.S. ships to China to 104%.

The increased Chinese tariffs on the U.S. will make it more costly for U.S.-based public Bitcoin mining companies to purchase ASICs (the premier machines used to mine bitcoin), the majority of which are produced in China.

And this will be largely beneficial for the health of the Bitcoin mining ecosystem.

As Troy Cross eloquently explained in “The Future OF Bitcoin Mining Is Distributed”, if one country controls too much of the Bitcoin hashrate, Bitcoin’s censorship resistance — one of its core value propositions — is put at risk.

In the article, Cross highlighted that if the majority of the Bitcoin network’s hashrate is not only produced in the U.S. but produced by American public mining companies, the U.S. government has more leverage to mandate that these companies only mine OFAC-compliant blocks.

For those who believe that these companies would push back or simply not follow such orders, please note that Marathon Digital Holdings, the largest publicly-traded Bitcoin mining company in the U.S., has already proven that it’s willing to comply with OFAC regulations.

The Bitcoin network has a higher likelihood of maintaining its censorship resistance when the hashrate is distributed globally.

As Cross mentioned in a recent interview (below), Bitcoin differs from other emerging technologies in that it does not benefit from one country controlling most of the industry around it.

He acknowledges that this isn’t necessarily intuitive, and that the notion may be confusing to the likes of those who are behind President Trump when he declares that he wants “all bitcoin made in the U.S.A.”

With the Bitcoin network, it’s best for countries to control a sizable portion of the network but not more than 50% of it.

And as Cross mentioned in the interview above, he believes that the U.S. may already control more than 50% of the hashrate.

However, this trend may now begin to reverse in the wake of China’s tariff increase on the U.S., because it will now be cheaper for the competitors of public U.S.-based Bitcoin miners to obtain ASICs than it will be for these companies.

So, while the escalating tariff war may be incredibly anxiety-inducing on a number of levels, consider taking some solace in the fact that it may be good for Bitcoin.

Source link

In a recent video interview by Bitcoin Magazine, Troy Cross, Professor of Philosophy and Humanities at Reed College, delves into the topic of his latest article for Bitcoin Magazine’s “The Mining Issue,” titled “Why the Future of Bitcoin Mining is Distributed.” Watch the full discussion here.

In the interview, Troy explores the centralization vectors in Bitcoin mining and presents a compelling argument for the decentralization of hashrate. Despite the economies of scale that have given rise to mega mining operations, he highlights a critical—and potentially economic—imperative for distributing mining power, offering insights into the future of Bitcoin’s infrastructure.

The following article is featured in Bitcoin Magazine’s “The Mining Issue”. Subscribe to receive your copy.

Intro

When Donald Trump said he wants all the remaining bitcoin to be “MADE IN THE USA!!!” Bitcoiners cheered. Mining is good, right? We want it to happen here! And indeed, the U.S. is well on its way to dominating the industry. Publicly listed U.S. miners alone are responsible for 29% of Bitcoin’s hashrate — a percentage that only seems to be growing. Pierre Rochard, vice president of research at Riot Platforms, predicts that by 2028, U.S. miners will produce 60% of the hashrate.

But let’s be honest: Concentrating most Bitcoin mining in the U.S., especially in large public miners (as opposed to a Bitaxe in every bedroom), is a terrible idea. If the majority of miners reside in a single nation, especially a nation as rich and powerful as the U.S., miner behavior would be driven not only by Satoshi’s well-designed incentives but also by the political whims of whatever regime happens to be in power. If Trump ever gets what he said he wants, the very future of bitcoin as non-state money would be at risk.

In what follows, I outline what a nation-state attack on bitcoin through the regulation of miners would look like. Then I review the incentive structures that have pushed Bitcoin mining to large U.S. data centers under the control of a handful of companies. Finally, I make the case that the future of Bitcoin mining does not resemble its recent past. Bitcoin mining, I think, will revert to a distribution closer to its early days, where miners were as plentiful and as geographically dispersed as the nodes themselves.

I also argue that despite some Bitcoiners’ enthusiasm for “hash wars”, and despite political chest-thumping, nation-states actually have an interest in a future in which no country dominates Bitcoin mining. This “non-dominance dynamic” sets bitcoin apart from other technologies, including weapons, where the payoff for dominating drives nations in a competition to corner the market first. But with Bitcoin mining, dominating is losing. When nation-states come to understand this very unique game theory, they will help defend it against miner concentration.

The Attack

If the U.S. had the majority of hashrate, how could bitcoin be attacked?

With a single directive from the Treasury Department, the U.S. government could order miners to blacklist certain addresses from, say, North Korea or Iran. The government could also forbid miners from building on top of chains with forbidden blocks, i.e., all miners would be forbidden from adding a block to a chain containing an earlier block with a censored transaction. Large U.S. miners — public companies — would then have no choice but to follow the law; executives don’t want to go to prison.

What’s more, even miners outside the U.S., or private miners within the U.S. choosing to flout the law, would have to censor. Why? If a rogue miner snuck a forbidden transaction into a block, law-abiding miners would have to orphan that block, building directly atop of earlier, government-approved blocks. Orphaning the block would mean the rogue miner’s own reward, their coinbase transaction, would be orphaned as well, leaving the miner with nothing to show for their work.

What would happen next is unclear to me, but none of the outcomes are ideal. We would have a fork of some kind. The new fork could use a different algorithm, making all existing ASICs incompatible with the new chain. Alternatively, the fork could keep the existing algorithm, but manually invalidate blocks coming from known bad actors. Either option would leave us with a government-compliant bitcoin and a noncompliant bitcoin, where the government-compliant fork would run the original code.

When I’ve heard Bitcoiners discuss these scenarios, they usually say everyone would dump “government coin”, and buy “freedom coin”. But would that really happen? Maybe we, the readers of Bitcoin Magazine, freedom seekers, and cypherpunk types, would dump the censored fork bitcoin for the new freedom variant. But I doubt that BlackRock, Coinbase, Fidelity, and the rest of Wall Street would follow suit. So the relative economic value of these two forks, particularly another five to ten years into the future, is far from clear to me. Even if a noncompliant fork of bitcoin were to survive and retain much of its economic value, it would be weakened economically and philosophically.

Now consider the same attack scenario but with well-distributed hashrate. Suppose U.S. miners represent only 25% of the hashrate. Suppose the U.S. government forces miners to blacklist addresses, and worse, orphan any new blocks containing transactions with blacklisted addresses. This is still bad. But the 75% of miners outside of the reach of U.S. law would continue to include noncompliant transactions, so the heaviest chain would still include noncompliant blocks. If there is a fork in this distributed-mining scenario, it is the government-compliant bitcoin that would have to fork away and abandon proof of work for social consensus.

This is still a dark scenario. Custodial services in the U.S. may be forced to support the new compliant bitcoin, and that would pose an economic threat, at least for a time, to the real bitcoin. But if the mining network persists outside the U.S. and has the majority of hashrate, this seems more like the U.S. opting out of bitcoin than the U.S. co-opting bitcoin, as it could with hashrate dominance.

How Did Bitcoin Mining End up in Large U.S. Data Centers?

Bitcoin mining’s evolution is a case study in economies of scale.

Let’s go back to the beginning. What we think of as the distinctive functions of miners — collecting transactions into blocks, doing proof of work, and publishing their blocks to the network — were all part of Satoshi’s descriptions of what nodes do. There were no distinctive “miners”; every node could mine with the click of a button. So in those early days, mining was as decentralized as the nodes themselves.

But CPU mining was quickly displaced by mining on graphics cards and FPGAs, and then from 2013 onward, by ASICs. Mining remained a vestigial option on nodes for many years, until in 2016 Bitcoin Core finally dropped the pretense and removed it entirely in version 0.13.0 of the software. Once mining took on a life of its own, apart from node running, using its own specialized equipment and expertise, it started to scale. This was entirely predictable.

In The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith describes a pin factory employing only 10 people that produces 48,000 pins per day, where each employee, all on their own, could make at most 1 pin per day. By specializing in one stage of the pin-making process, developing tools for each subtask, and combining their efforts sequentially, the employees produced far more pins with the same amount of labor. One way to think about this is that the cost of increasing production by one pin is negligible for a factory already making 48,000, having already sunk cost into the equipment and skills; it would only require a slight addition of labor and materials. But for someone producing one pin a day, the marginal cost of adding one pin to production doubles.

Mining, once freed from the CPU, had many features that lent themselves to efficiencies of scale just like making pins in a pin factory. ASICs are specialized tooling, like pin-making machines. So are the data centers designed for the special power density and cooling needs of those ASICs. Likewise, compared to mining in one’s basement, mining in a multi-megawatt commercial facility spreads the same fixed costs over many more mining units. Some examples of relatively scale-indifferent expenses encountered by miners include:

- Power expertise

- Power equipment

- Control systems expertise

- ASIC repair expertise

- Cooling expertise

- Cooling facilities

- Legal expertise

- Finance expertise

In a larger operation, not only are fixed costs absorbed by a larger number of revenue-producing machines, but one also gains bargaining power with suppliers and labor. Scaling up from one’s basement to the local commercial park, one gets a better price on electricity. Scaling up from an office park presence to a mega-center, one begins to employ power specialists who draw up sophisticated contracts with power suppliers and financially hedge against price movements. Sending one machine off for repair whenever it breaks down costs more — per repair incident — than simply hiring a repair specialist to find failing ASICs and fix them on-site, provided the scale of operation is large enough. And when dealing with ASIC manufacturers, pricing is relative to the size of the order. Major players can drive a harder bargain, squeezing smaller miners like Walmart squeezed main street shops by negotiating lower prices for their wares.

Economies of scale should surprise no one, as they apply to some degree to almost all manufactured goods. The benefits of size naturally explain how mining went from something I did with graphics cards in my basement 13 years ago to facilities approaching 1 GW today.

But that is why mining has scaled up, not why it has concentrated in the U.S. and in large public companies. To understand the latter requires noticing two more factors. The first is another good that scales: financing. Large public companies can raise cash through diluting their stock or issuing bonds. Neither of these fundraising mechanisms is available to a small-scale miner. True, they can borrow, but not on the same terms as a large company, and the U.S. has the deepest capital markets in the world. Secondly, the U.S. has “rule of law”, a relatively stable legal system, reducing the risk that, for instance, the state would seize a mining operation or that regulators would arbitrarily halt operations.

The other feature that drew mining to the U.S. in the past few years was the availability of power infrastructure. After China banned Bitcoin mining, it became profitable to mine virtually anywhere in the world with basically any ASIC. But the U.S. had available power infrastructure, much of it in the rust belt, left behind when U.S. manufacturing made an exit for China. The U.S. also had abundant power in West Texas, stranded wind and solar energy incentivized by subsidies but insufficiently interconnected to East Texas and to the rest of the country. In the wake of the China Ban, miners quickly occupied the underutilized rust-belt infrastructure and took advantage of the abundant power and cheap land to build data centers in West Texas.

The ability to raise and deploy large amounts of funding is a striking advantage, and one that compounds with others, given Bitcoin mining’s fixed, global reward. With ample funding from the markets, the largest public Bitcoin miners were able to secure the newest, most efficient, and most powerful ASICs as well as negotiate the best power contracts, hire the best experts on firmware and software, and so on. Not only did this put smaller miners at a disadvantage, but the large miners could then boost global hashrate significantly, driving up difficulty. When the price of bitcoin fell, with a debt-fueled ASIC fleet already deployed, margins shrank to almost nothing for miners that did not have the advantages of scale. Even a public miner in bankruptcy could continue running their massive fleet of machines during restructuring, driving out their smaller competitors while navigating the legal system.

Thus did mining grow from hobbyist scale to gigawatt scale, and thus did it settle in America. Mining is a brutally competitive commodity business, and the efficiencies afforded by scale proved decisive, especially when funded by debt and dilution.

Why Mining Will Be Distributed and Small-Scale Once Again

Just as there are economies of scale, there are also diseconomies of scale, where unit production costs actually increase with size at a certain point. For instance, it’s obvious why there isn’t just one gigantic food factory that feeds everyone in the world every meal. Yes, there are efficiencies in the factory production of food — witness the average farm size over the past century — but there are limits too. Fresh ingredients must be shipped to a factory and the final product then must be shipped to consumers. Both the inputs and the outputs of a food factory are perishable and heavy. Shipping costs to and from a single factory would be exorbitant, and quality would suffer in comparison to more local markets with fresher food. Similar factors explain why sawmills and paper mills are near forests, and why bottling plants are near fresh water.

But shipping bitcoin costs nothing: It’s a simple matter of making a ledger entry on the Bitcoin blockchain itself, which takes mere seconds. And although I like to brag about mining our artisanal Portland bitcoin, there are actually no local flavors of bitcoin that differ depending on where it’s made. All bitcoin is qualitatively identical. This is all the more reason global bitcoin production should centralize to the single, very best place to make bitcoin.

There’s just one problem with centralizing all mining into a single plant: Bitcoin mining is energy-intensive. In fact, it already uses more than 1% of the world’s electricity. Electricity is the primary operating cost of mining bitcoin, often representing 80% of operating expenses. And unlike bitcoin, electricity does not travel well. Not at all. In fact, electricity is a lot like food that perishes instantly and requires expensive, specialized infrastructure to transport. For electricity, that infrastructure is wires, transformers, substations, and so on — all the elements of an electrical grid.

Shipping electricity is actually much of the cost of electricity. What we call “generation” is often a minority of the total cost of electricity, which also includes “transmission and distribution” charges. And while the cost of generation continues to fall with advances in technology and manufacturing efficiency for solar panels, grid investments are only becoming more costly. So it makes no sense to ship electricity around the globe to a single bitcoin factory. Instead, bitcoin factories should sit at the sites of generation where they can avoid transmission and distribution costs altogether, and then ship the bitcoin from those sites for free. This is already happening, in fact. It’s called putting your Bitcoin mine “behind the meter”.

Mining companies will play up their differences: firmware, pools, cooling systems, finance, power expertise, management teams. But at the core of what they do, there is little to separate different mining companies from one another: The product is identical, it costs nothing to ship, and they use exactly the same machines (ASICs) to convert electricity to bitcoin. Differences in electricity cost largely determine which miners will survive and which will not. In a prolonged period of price stagnation, or even a steady rise, only those companies with access to the cheapest electricity will be operating.

The master argument, then, for a global distribution of miners in the future goes as follows. First, Bitcoin mining, by design, is driven to the cheapest energy in the world. Second, cheap energy is distributed around the world, and also “behind the meter”. So, third, mining will be geographically distributed and behind the meter too.

For the sake of argument, imagine Donald Trump’s wish is granted and all mining is in the U.S. and that mining is in equilibrium, i.e., mining margins are extremely tight. If someone finds power elsewhere in the world that is cheaper than the average U.S. miner’s, and deploys ASICs there, hashrate will increase and some U.S. miners (those with the highest expenses) will go out of business. This process will repeat until mining only happens on the cheapest energy in the world.

Cheap energy takes different forms: gas in the Middle East and in Russia; hydro projects in Kenya and Paraguay; solar in Australia, Morocco, and Texas. The reason energy is distributed is that nature has distributed it. Rain and elevation changes (i.e., rivers) are everywhere. Fossil fuel deposits are everywhere. The wind blows everywhere. The sun shines almost everywhere.

In fact, the global distribution of energy is somewhat guaranteed by the solar path around the planet. As the sun shines most brightly, its energy is bound to be wasted by solar-powered systems, as power infrastructure is never designed for peak generation. I predict that in the future, a substantial portion of the hashrate will follow the solar path, with machines using the excess solar either overclocking during that period or, if they are older and otherwise unprofitable, turning on only for that brief period when the system is producing more electricity than the grid demands.

The master argument above can be slightly modified to reach other conclusions about the future of mining. I also think, for example, that there is abundant cheap power at a small scale, and a limited amount of cheap power at a truly massive scale (100 MW+). It follows that, provided Bitcoin mining continues to grow, small-scale mining will make a return and the trend toward megamines will reverse as large-scale sources of cheap power disappear.

To see why cheap power exists mostly at the small scale, we could go on a case-by-case basis. For instance, we could look at why flare-gas waste happens in a distributed small-scale way, and why solar inverters are undersized, leading to clipped power all over the system. But I would rather think about the broader principle. Where we have cheap power at scale it is a massive mistake. For instance, the mistake may be building a dam or nuclear plant no one really needed. Massive mistakes are limited in number: They’re expensive! There is a limit to fiat stupidity.

Smaller-scale mismatches of supply and demand are going to be more common, all else equal. If gas production at an oil well is big enough, for instance, it will make sense to build a pipeline to ship it out; if it’s relatively small, it will not make sense to build the pipeline and the gas will be stranded. Likewise for landfills. The largest landfills have generators and are grid-connected, but the smaller landfills often fall short of even collecting their methane, let alone generating electricity with it and feeding that electricity to the grid. The same is true of dairy farms.

Further, bitcoin is not the only form of energy-intensive computation. If there are large quantities of cheap energy, other forms of computation will take up residence there and, being less sensitive to the price of electricity, they will outbid bitcoin miners. Those other forms, at least at present, do not scale down as well as bitcoin. It follows that the days of mining on supercheap, large-scale power are numbered. On the other hand, if you are mining bitcoin by mitigating flare gas on a desolate, windswept oil patch far from a pipeline, there is virtually no chance anyone will outbid you in order to do AI inference at your location. The same is true if you are mining on overprovisioned home solar. Small-scale energy waste is far less appealing to competitors but usable for Bitcoin miners. Mining can scale down enough to reach into these crevices of energy, whereas other kinds of energy consumers cannot.

Another version of the argument above trades on the distributed demand for waste heat. All of the electrical energy entering a bitcoin miner is conserved and leaves the miner as low-grade heat. With this waste energy, miners are heating greenhouses, villages, and bathhouses. But heating needs can typically be met with a small deployment of machines. An ASIC or two can heat a home or a swimming pool. Yet using waste heat to substitute for electrical heating improves the overall economics of mining. Other things equal, a miner selling their heat will be more profitable than a miner not selling their heat. So here is another argument that mining will be globally distributed and smaller scale: The demand for heat is globally distributed — though greater in the far north and south — and at a very limited scale.

As I’ve said, I believe Bitcoin mining will be driven to the world’s cheapest energy. But this is the trend only if the price of bitcoin rises slowly. In an aggressive bull market — and we have seen several — Bitcoin miners will use any energy available, wherever they can plug in machines. If bitcoin’s price rockets to $500,000, all my models are destroyed. But in this bullish scenario, too, mining becomes globally distributed, this time not because the cheapest power is distributed but because available power is distributed. Bitcoin at $500,000 means all ASICs are profitable on any power, and the U.S. alone does not have the infrastructure to handle that kind of demand shock even if it wanted to. So, bitcoin will be distributed either way.

It is worth noting, too, that high-margin times are short-lived, as ASIC production will always catch up, in the pursuit of profits, driving margins back down. So, over the long term, the distribution of Bitcoin miners will still be determined by the distribution of the world’s cheapest energy.

For my arguments to work, the diseconomies of scale must outweigh the economies of scale listed above. To determine the balance of these two requires nothing less than a deep dive into the spreadsheets of each kind of mining business, which would be inappropriate here.

Suffice it to say I believe that if the difference in the cost of electricity is great enough, then it outweighs everything else. But I can’t pretend to have provided anything like a proof here. These are the broad strokes; the finer details remain an exercise for the reader.

Geopolitics

Thus far, I’ve contemplated miner incentives without regard to nation-states themselves. We know that just as some countries are buying bitcoin, others are mining bitcoin with their energy resources. Nation-states have incentives independent of anything Satoshi contemplated. For instance, Iran may mine bitcoin in order to monetize its oil because sanctions make selling it on the open market impossible, or expensive at any rate. Russia may mine for similar reasons. Such nation-state actors could “mine at a loss” relative to a miner paying for their own power, because the nation-state’s cost of energy is subsidized by the taxpayer. Their mining at scale, in turn, could make it less profitable for everyone else, and push marginally profitable miners out of business.

I do not see nation-state mining as ultimately concentrating hashpower, however. As things stand, mining in Russia and Iran is actually good for bitcoin, as it checks the advance of mining by U.S. public companies, which dwarf them in scale. Moreover, if some nation-state begins to produce a disproportionate share of the hashrate, while bitcoin is an important piece of the global economy, I expect other nation-states with a stake in bitcoin’s success — or even large bitcoin holders — would also begin to mine at a loss in order to keep mining decentralized.

The game theory here is not intuitive. Rather than a competition to dominate, bitcoin is a game in which everyone wins when no one dominates and everyone loses when anyone dominates. For virtually every other technology or weapons system in the world, the best strategy is to achieve global dominance. Thus, we see a race to dominance in battery technology, chip manufacturing, drones, AI, and so on. This is called the “Thucydides trap” in foreign policy because it dictates a preemptive attack on a rising rival: The reward is immense for coming in first, and the loss is incalculable for coming in second.

But if you dominate Bitcoin mining, that is bad for Bitcoin mining, and therefore bad for bitcoin and therefore bad for you. As Bitcoin mining concentrates in one nation, everyone sees the possibility of an attack on the neutrality of bitcoin, which lies at the core of its value proposition. For instance, Russia might hold bitcoin to avoid the U.S. freezing its reserves, as the U.S. did with Russia’s fiat reserves upon their invasion of Ukraine. But if mining is concentrated in the U.S., Russia could not trust that their addresses wouldn’t be blacklisted by the U.S. Treasury Department. Russia, therefore, would dump its bitcoin for some other asset if it saw this threat arising. Miners in the U.S. would see their share of block rewards rise as they achieved dominance over other miners, but the value of their block rewards would drop as the price of bitcoin itself dropped. Other things equal, then, miners in the U.S. would not want Russians to stop mining and dump their bitcoin. U.S. miners should not want to “win”, at least not in this way. And if bitcoin is a meaningful enough part of the U.S. economy, the U.S. itself should not want its miners to win. Rather, if any nation approaches dominance, we should expect those heavily invested in bitcoin, including nation-states, to mine enough to prevent losses to their own investments.

Bitcoiners should hope that the USA will mine enough bitcoin that no country, including itself, mines a majority of it. That’s a terrible slogan for a campaign rally, and it doesn’t capture the imagination like “hash wars”. But as a Bitcoiner, it is the only rational preference one should have.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed are entirely the author’s and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.

Source link

Futureverse Acquires Candy Digital, Taps DC Comics and Netflix IP to Boost Metaverse Strategy

Court Grants Ripple And SEC’s Joint Motion To Suspend Appeal

AVAX Falls 2.1% as Nearly All Assets Trade Lower

What is a VTuber, and how do you become one in 2025?

Top Expert’s Update Sets $10 Target

How Academia Interacts With The Bitcoin Ecosystem

AB DAO and Bitget Launch Dual Reward Campaign, Distributing $2.6M Worth of $AB Globally

AI crypto tokens at risk as Nvidia faces restrictions on China exports

Coinbase Urges Australia to Vote for Crypto Progress in May

How High Would Pi Network Price Go If Pi Coin Adopts Transparency to Avoid Mantra Pitfalls

XRP’s ‘Rising Wedge’ Breakdown Puts Focus on $1.6 Price Support

China selling seized crypto to top up coffers as economy slows: Report

Ethereum Price Dips Again—Time to Panic or Opportunity to Buy?

The Inverse Of Clown World”

Bitcoin Indicator Flashing Bullish for First Time in 18 Weeks, Says Analyst Who Called May 2021 Crypto Collapse

Arthur Hayes, Murad’s Prediction For Meme Coins, AI & DeFi Coins For 2025

Expert Sees Bitcoin Dipping To $50K While Bullish Signs Persist

Aptos Leverages Chainlink To Enhance Scalability and Data Access

Bitcoin Could Rally to $80,000 on the Eve of US Elections

Crypto’s Big Trump Gamble Is Risky

Sonic Now ‘Golden Standard’ of Layer-2s After Scaling Transactions to 16,000+ per Second, Says Andre Cronje

Institutional Investors Go All In on Crypto as 57% Plan to Boost Allocations as Bull Run Heats Up, Sygnum Survey Reveals

Ripple-SEC Case Ends, But These 3 Rivals Could Jump 500x

3 Voting Polls Show Why Ripple’s XRP Price Could Hit $10 Soon

Has The Bitcoin Price Already Peaked?

A16z-backed Espresso announces mainnet launch of core product

The Future of Bitcoin: Scaling, Institutional Adoption, and Strategic Reserves with Rich Rines

Xmas Altcoin Rally Insights by BNM Agent I

Blockchain groups challenge new broker reporting rule

I’m Grateful for Trump’s Embrace of Bitcoin

Trending

24/7 Cryptocurrency News5 months ago

24/7 Cryptocurrency News5 months agoArthur Hayes, Murad’s Prediction For Meme Coins, AI & DeFi Coins For 2025

Bitcoin3 months ago

Bitcoin3 months agoExpert Sees Bitcoin Dipping To $50K While Bullish Signs Persist

24/7 Cryptocurrency News3 months ago

24/7 Cryptocurrency News3 months agoAptos Leverages Chainlink To Enhance Scalability and Data Access

Bitcoin5 months ago

Bitcoin5 months agoBitcoin Could Rally to $80,000 on the Eve of US Elections

Opinion5 months ago

Opinion5 months agoCrypto’s Big Trump Gamble Is Risky

Altcoins3 months ago

Altcoins3 months agoSonic Now ‘Golden Standard’ of Layer-2s After Scaling Transactions to 16,000+ per Second, Says Andre Cronje

Bitcoin5 months ago

Bitcoin5 months agoInstitutional Investors Go All In on Crypto as 57% Plan to Boost Allocations as Bull Run Heats Up, Sygnum Survey Reveals

Price analysis5 months ago

Price analysis5 months agoRipple-SEC Case Ends, But These 3 Rivals Could Jump 500x