Culture

Bitcoin’s False Dichotomy between SoV and MoE

Published

2 months agoon

By

admin

This post is long overdue.

I talk about Bitcoin a lot. In any given week, I’ll have dozens of conversations about bitcoin with various people across different sectors. And like a pendulum oscillating every other year, the narrative of bitcoin not being a medium of exchange keeps coming back. I get it. When influencers from the community are pushing this narrative, people listen. They’re influencers.

But in this post, I want to set the record straight: Bitcoin IS a medium of exchange, now and in the future. What’s more, its future as a store of value (SoV) depends on its acceptance as a medium of exchange (MoE). Some of the people pushing the (false) dichotomy between bitcoin as a SoV and a MoE are doing it for their own self-interest. Some are just hangers-on.

Luckily, these people do not control how bitcoin will continue to develop and be developed. Bitcoin’s future depends on our collective swarm intelligence, and together we’re pretty smart. Here’s the conclusion we will eventually, inevitably reach: the dichotomy of bitcoin is no dichotomy at all. Bitcoin’s durability and deflationary properties are what make it a good SoV. Its divisibility, portability, relative fungibility — along with its decentralization and censorship-resistance — are what make bitcoin a good MoE. But these qualities presuppose each other. Indeed, you can’t have a SoV without a MoE.

There Is No Value Without Exchange

Before determining how the categories of SoV and MoE fit together, we should establish what those terms mean in the first place. While there are conceptual differences between them, neither is really thinkable without the other. There is no SoV without a MoE and vice versa.

SoVs Trade Across Time

Stores of value need to be durable, and they need to retain their value. So far, so obvious. But what does it mean to “retain value”? How could you tell?

There are several ideas about how best to think about value. Marx famously reduced value to labor, so the more labor was invested in producing a thing, the more it would be worth. But this just begs the question: what’s a unit of labor worth? And is a wild strawberry worth less than a cultivated one, even if it’s more delicious?

Then there’s “intrinsic” or “objective” value. In finance, intrinsic value means something like the “true” or “objective” value of an asset as distinguished from its market price, which is supposedly distorted by all the market participants and their (mis)perceptions. A company with plenty of quality machines and a positive bank balance would seem to have value even if its shares were worthless. In strict semantics, intrinsic value would mean that the value is inherent, in the essence of the thing.

But all value is contextual. In the middle of the desert, a barrel of water is worth more than all the gold in the world. The fastest mining rig ever devised is worth nothing to a sadhu. Family heirlooms like your late grandma’s favorite earrings are worth incalculably more to members of that family than to anyone else. You won’t find their value in their objective characteristics.

That’s why many economists and mainstream bitcoiners subscribe to the subjective theory of value. The idea is that there is no value in a transactional vacuum. Value emerges from how people deal with a thing, what they’re willing to trade for it. At some point, aggregate supply will meet aggregate demand – the price – and that’s where the trades will happen.

A price is just the value of one thing expressed in a quantity of something else. A Tag Heuer Connected Calibre E4 trades for $1450 USD, which is equivalent to about 0.02 btc, which is equivalent to …

That’s the first important conceptual point about SoVs: unless they are exchanged sometime, they have no real value. They might have notional value, like the value of an imaginary pet dragon, but their real value would never have the chance to emerge.

The second point is that all SoVs imply a trade by definition; it’s just that the trade is diachronic. In other words, the trade with a SoV is in the same asset at two points in time. Trade a smaller value of thing A in the present for a larger value of thing A in the future. Same asset, two different times.

While we’re thinking about time, consider this: what does it mean for a SoV to appreciate? Its value must be measured relative to something else. In other words, appreciation simply means that its future real price will exceed its current real price; I’ll be able to exchange less of it for more stuff in the future than I can today. Without a trade — even just an unrealized future trade — there is no value.

MoEs Trade Across Assets

MoEs need to be divisible, portable, and fungible. Here the trade is synchronic (at the same time) across different assets rather across time (diachronic) with the same asset. But if MoEs are traded in the present by definition, how short is the present? What’s worth more: owning all the bitcoin that’s ever been mined, but only for one femtosecond, or ten million durable sats?

Some amount of value retention and durability is necessary for a MoE to work. For example, cigarettes are used as currency in prison. But cigarettes go stale after a few weeks, so they don’t retain value very well over time. Those who have them are looking to spend them quickly. Ditto shitcoins whose value might collapse next week. You need to take the trade or reject it now.

Indeed, durability is one of the characteristics that make gold a better MoE than, say, sodium. Gold resists almost any kind of corrosion, so our descendants will still have the same amount of gold to trade generations from now, whereas sodium can’t even get wet without exploding.

So even though conceptually MoEs are exchanged instantaneously in the present, practically speaking they exist in a temporal world of people with finite lifespans, short vacations, and long hours in waiting rooms. A MoE that retains its value is worth more than a perishable MoE, other things being equal. (Interesting wrinkle: when perishability increases scarcity, but let’s not digress.)

And MoEs reinforce the subjective theory of value. If no one wants to buy your artisanal pumpkin spice pasta for the price you’re asking, can you say that everyone is wrong? That no one recognizes its intrinsic value or the value of the hours you’ve invested in making it? Of course not. That monstrosity is worth what people are willing to exchange for it, nothing more and nothing less. Without a subjective, contextual theory of value, it’s hard to conceptualize a MoE in the first place.

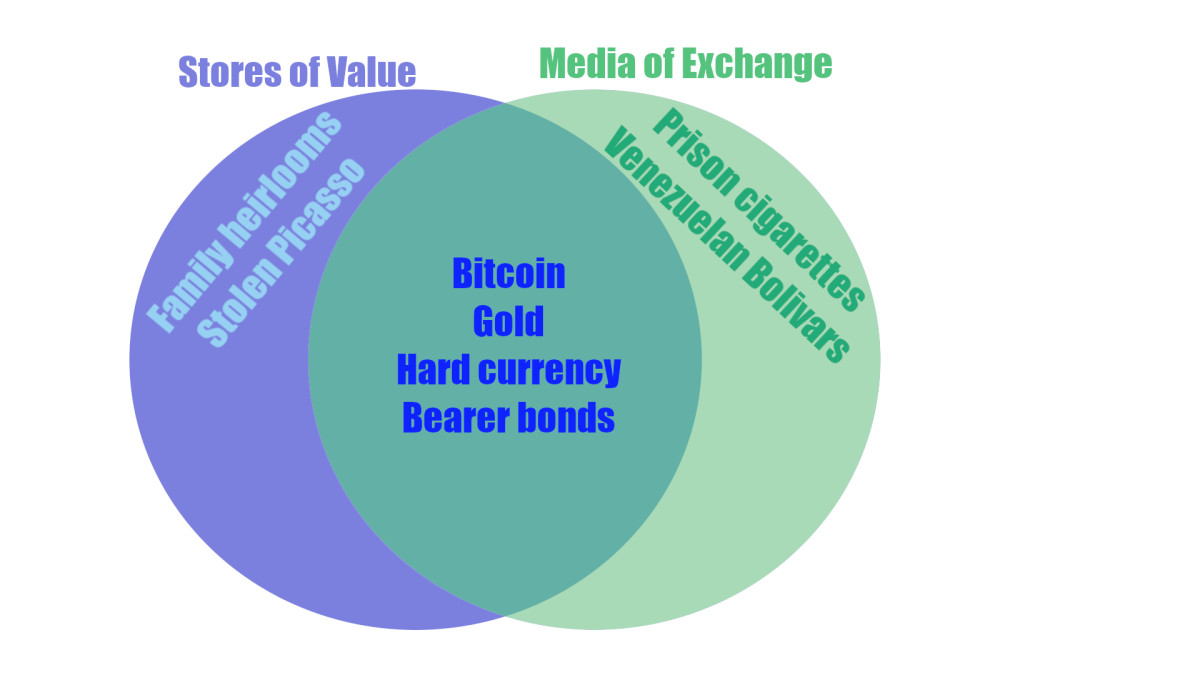

SoV-MoE Convergence

So there are a few edge cases on each side, where the properties of the asset recommend it as either a SoV or a MoE. The harder an asset is to trade, the more it would seem like a SoV. The quicker an asset degrades, the more it would seem like a MoE, up to a point. Without some tradability, a SoV is worthless and no longer a SoV. Without some durability, a MoE is worthless and no longer a MoE. But some assets fall more on one side or the other.

The middle, however, is far from empty. That’s where you’ll find the really good stuff, like gold, bearer bonds, hard currency, and bitcoin of course. What makes them great is that they share the attributes of both SoVs and MoEs. These assets are more or less fungible, portable, and divisible, just like good MoEs. And their value is durable, just like good SoVs.

If people trade them at high velocity, they look more like MoEs. If trades occur at longer intervals, then they look more like SoVs. The substance is the same; it’s the context and the activity that changes how we see them.

Contrast this happy coincidence with the claim of dichotomy. That is, what is bitcoin as a SoV exclusively, i.e. without working as a MoE? Rather than recognize and realize bitcoin’s potential, the SoV-only hypothesis absolves it from ever having to trade. But since value emerges from transactions, never in a vacuum, a SoV that never functions as a MoE has no detectable value.

The idea that bitcoin is only a SoV is not even wrong. It’s incoherent. It’s asserting that bitcoin is a store of value while removing it from the only kinds of context that could allow us to determine its value. SoV and MoE are logically and practically inseparable. A SoV is a MoE in transactional slow motion, and a MoE is a SoV with the trading velocity cranked up.

But enough theory. This is the way things have always been, or at least as far back as archaeology lets us see. We’ll return to bitcoin in a minute, but let’s look at its family tree first. The coincidence of SoVs and MoEs is an empirical reality that goes back millennia.

Storing and Trading Assets Through History

Beyond theory, history provides evidence for the convergence of SoVs and MoEs. History contains a host of assets that function as both MoEs and SoVs because if they’re in demand, you can trade them, and if you can trade them, then it’s good to have a stockpile in storage. SoV and MoE are – and always have been — two sides of the same, er, coin.

Bronze Ingots

The overlap between SoVs and MoEs is illustrated beautifully by Bronze Age oxhide ingots. These ingots were shaped like oxhides, came in roughly standardized weights (usually around 30 kg / 66 lbs.), contained relatively pure copper or tin, and were passed around all around the Mediterranean and beyond from the second millennium BCE — the Bronze Age.

Since everybody was using bronze, copper and tin – the two ingredients of bronze – held their value very well. Everybody could use them. Demand was high and stable. They were also relatively easy to store.

But they were also relatively easy to transport. A load of ingots found in a shipwreck from 1327 BCE contained metal that originated in Uzbekistan, Turkey, Sardinia and Cornwall. Chariots were still relatively new tech, but these hunks of metal were traversing the known world, farther than virtually any human would have traveled, because they were “connected to systems of international distribution, exchange and trade.”

Now let’s say that you’re a Bronze-Age fisherman who comes across a sunken cargo of ingots. Are they a SoV or a MoE? Well, if you’ve had a good season, you might be feeling flush, so you save them for a rainy day, in which case they’re a SoV. If, on the other hand, the fish haven’t been biting and you need some liquidity, then you’d probably trade them quickly, in which case they’re a MoE. But how would you know they were worth saving if they weren’t being traded somewhere to reveal their value? And who could you trade with if there weren’t counterparties out there convinced that owning some ingots around would be a wise financial decision?

The oxhide ingots’ durable, high-demand materials made them good SoVs, and their standardized sizes and portability made them good MoEs. The ingots were both simultaneously because each use implies the other.

Gold

Humans started collecting gold a few millennia before they were into bronze. But at first, gold was principally used for decorative and sacred purposes, like statues and ceremonial jewelry. Since such objects aren’t fungible, they were poor MoEs, and trades were very infrequent. The low trading velocity was due to the impossibility of finding a price: ceremonial objects’ owners would always value them more highly than any counterparty.

Standardized gold coins only started showing up around the 7th century BCE, about 1000 years after the ingots. Interestingly, they appeared in China and Anatolia around the same time. As coins, gold had finally become fungible, which increased the trading velocity and brought the SoV and MoE uses closer together. Coins also offered some advantages over oxhide ingots: a coin doesn’t weigh 30 kg, gold doesn’t corrode, and it didn’t have a lot of other uses, so the supply didn’t have to compete with demand for useful stuff like ploughs and swords made of bronze.

Gold coins were so effective as both a SoV and a MoE that basically everyone started using them, like the Roman aureus, the Almoravid dinar, the Spanish doubloon, the Tokugawa Koban, etc. Even now, 2600 years later, countries from Armenia to Tuvalu are minting and circulating gold coins for people to keep and trade, to store and exchange.

Again, the use of gold coins as a MoE made gold a more obvious and widespread SoV, and their widespread recognition as a SoV made them a more liquid MoE.

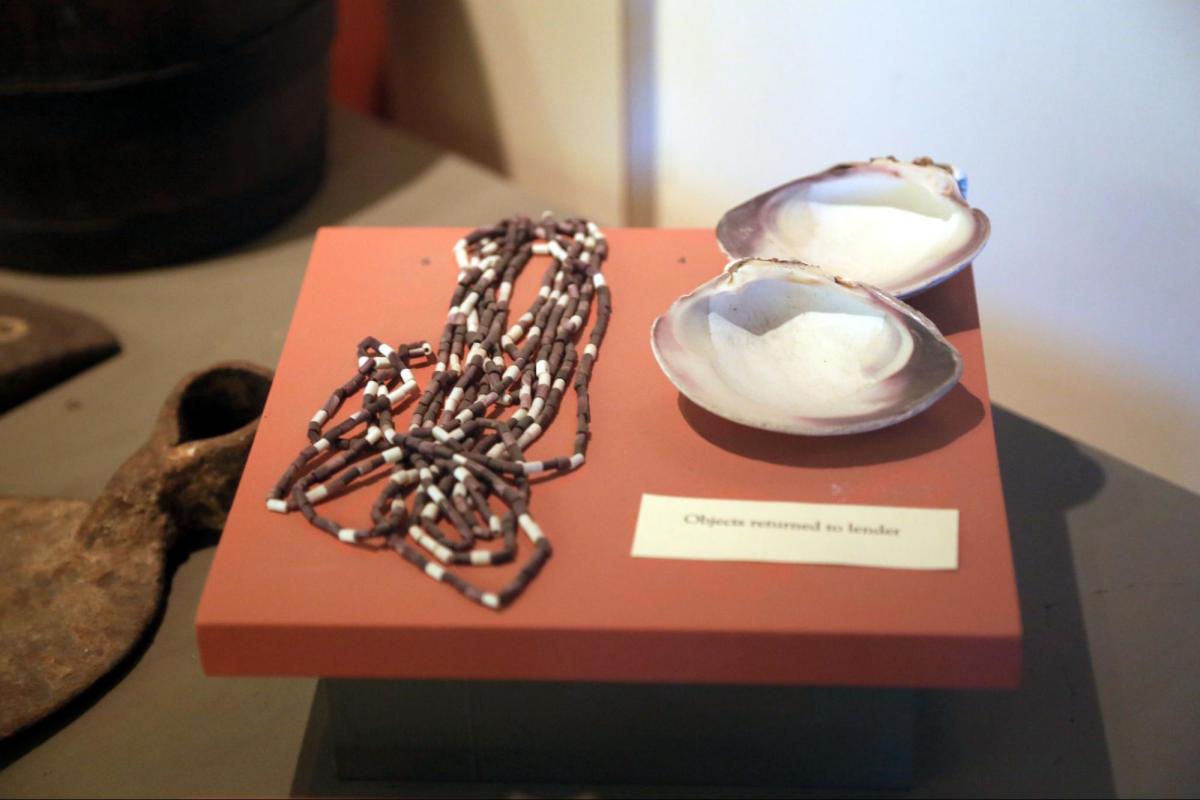

Wampum

In the 17th century, early European settlers on the Atlantic coast of North America and the indigenous peoples of the continent were getting to know each other. The worlds they knew were radically different. No common language, no common religion, no common history, radically different technology, radically different cosmologies. But as humans do, they started to trade pretty quickly. Without commonly recognized SoV-MoEs, though, trading is hard.

At first, fur pelts had a certain value, but they’re bulky, their value was not standardized, they can degrade, etc. They were better than nothing as a SoV and MoE, but not ideal as either. Venetian glass beads also worked, but getting beads from Venice to the European colonies in the “New World” could take months, maybe years.

Then in 1622 a Dutch trader named Jacques Elekens took a Pequot sachem (like a chieftain) hostage and demanded ransom. The sachem’s people brought Elekens 280 yards (~256 m) of white and purple beads made from clam shells – wampum. Apparently, they hadn’t really used wampum as cash before, and even in this instance the ransom had primarily symbolic value, like ransoming a prince by sending a fancy ceremonial scepter.

But Elekens was a trader, and though he missed the transcendent symbolic value of wampum, he saw its profane cash value immediately. If you can buy a chief’s freedom with wampum, what couldn’t you buy? Soon the Europeans were forcing a couple of tribes to produce wampum, and it was traded in units of length, like so-and-so many pelts for so-and-so many fathoms (1 fathom ~ 1.8 m / 6 ft.) of wampum beads.

Wampum quickly became an official MoE. Several colonies adopted wampum beads in standardized values as legal tender, a practice that continued for about a century. And wampum was naturally attractive as a SoV: “the European colonists quickly began trying to amass large quantities of this currency, and shifting control of this currency determined which power would have control of the European-Indigenous trade.” They weren’t just trading with it; they were building currency reserves. They were storing the MoE for its future value, and its future value made it an effective asset to trade today.

The words “gold” and “wampum” still mean money in certain contexts. Speaking of money…

The USD

The power to create money is enshrined in the US Constitution, and the Coinage Act of 1792 pegged the value of the new dollar to the Spanish silver dollar and a fixed quantity of 416 grains of silver. “Eagles” were effectively $10 coins that were to contain 270 grains of gold.

The architects of the dollar were leveraging the historical context that everyone already understood: precious metals work as both MoEs and SoVs. After three and a half millennia, word had got around.

As tends to happen with specie, the coins were debased over time, which means that the minters kept gradually lowering the amount of precious metals contained in the coins. That’s how inflation works with a MoE that’s pegged to keep its value as a SoV. You can still mint the same amount at less cost by manipulating the peg.

The Gold Standard Act of 1900 hardened the peg by making each dollar redeemable for a fixed amount of 25.8 grains of 90% pure gold. So if dollar notes were redeemable for gold, would that make them a MoE or a SoV? The notes circulated, but the US government was committed to storing an equivalent amount of gold to maintain their value. The gold might look like a SoV, and the notes might look like a MoE, but they were equivalent, so it’s only the use that differs, not any deeper nature.

When the Great Depression struck, there was a run on the Federal Reserve. People were concerned about the dollar’s continued viability as a MoE, so they started to redeem their dollars for gold. When the Federal Reserve became concerned about its own ability to continue converting dollars for gold, President Roosevelt suspended the gold standard.

But, of course, bank deposits didn’t fall to zero, so the dollar continued to function as a SoV and MoE. And people were hoarding gold so they could trade it just in case the dollar did lose its utility as a SoV and MoE. But both dollars and gold retained both functions.

The gold standard returned with the Bretton Woods system after the Second World War, but this time the USD was pegged at $35 per ounce of gold, and central banks around the world could exchange their dollars for gold at that rate. This effectively made the USD the hardest currency, and through fixed exchange rates it was supposed to bolster other currencies too. As before, the equivalence through redemption virtually erases any practical distinction between the SoV and the MoE.

For a range of complicated reasons that can be reductively simplified down to “inflationary pressure” (i.e. fiat’s own perverse version of “numbers go up”), the USA had to abandon the international gold standard of Bretton Woods in 1971.

While this was an important turning point for economic historians, the USD remains both a SoV and a MoE. According to the IMF, about 60% of global foreign exchange reserves are held in USD, about 3x as much as the nearest competitor. Other countries store USD just in case they need to exchange it for their own currency to prop up their own currency’s value or to buy necessities in a pinch.

Even without gold backing, demand for USD is astounding. Foreign countries hold $8.8 trillion of American debt — IOUs to be paid in dollars at some point in the future, which looks like a classic SoV. And most international trade is billed and settled in USD. Even in Europe, a continent with its own common currency, over 20% of trade is settled in dollars.

The remarkably resilient demand for greenbacks gives the USA as their minter a privileged position. The phenomenon of “petrodollars” illustrates just how the USD has remained dominant since the collapse of the gold standard. Petroleum exporters sell oil for USD, and they rapidly accumulate large reserves of dollars. They need to spend these dollars, and it just so happens that the US is always eager to sell T-Bills (American I.O.U.s) for dollars to finance its $35 trillion in debt.

As long as other countries hold that debt, they have an interest in preserving the value of the dollar. As long as the dollar can retain its value, it remains useful for trade. As long as it remains useful for trade, other countries will accumulate dollars and dollar-denominated debt. Sound like a Ponzi scheme? Well, it’s not not a Ponzi scheme.

In short, other countries’ foreign reserves of USD let the US trade on a multiple. Hold that thought.

Yes, Bitcoin Is a SoV Is a MoE

Bitcoin is the latest descendant in this lineage of readily tradable SoVs, i.e. of MoEs that people like to hoard because they hold their value. However, there is a widespread, often repeated claim that bitcoin is just a SoV. Indeed, that’s why I’m writing this, and that’s why I feel the burden of proof is on me to demonstrate bitcoin’s viability as a MoE. So far I’ve laid out some theoretical ideas about how SoVs and MoEs are conceptually inseparable and covered several historical examples to demonstrate that this mutual presupposition is how things have worked as far back as history can go. So now let’s turn to bitcoin, which is just new tech following established patterns: MoE and SoV go together because they must.

Transactions in the Trillions

We know bitcoin works as a MoE because people move bitcoin – A LOT. Adjusting for change addresses, River estimates that $14.9T of payments were settled with bitcoin in 2022. So even if 74% of bitcoins don’t move within six months, bitcoin equivalent to the combined GDPs of Germany, Japan, India, and Canada can change hands in just a year.

Trading Bitcoin

There are about 2.35 million btc in exchange accounts (about $150B). This should be puzzling because autonomy and self-custody are two of bitcoin’s major selling points. If bitcoin is just a SoV, why would anyone entrust it to another party rather than keeping it in cold storage themselves? If it’s a store of value, why wouldn’t you store it as safely as possible, especially considering that decently safe storage can cost as little as a piece of paper?

The reason more than one in ten of all bitcoins in existence are held in exchange accounts is to facilitate trading. Exchanges are just that: where people go to trade one asset for another. Bitcoin works beautifully as a MoE for such trades because no other cryptocurrency even comes close to the demand for bitcoin. Whether you go by market cap or unit price, bitcoin is in a league of its own. The only other coin that can compete on any interesting metric is USDT, whose trading volume is roughly double bitcoin’s impressive $26 billion/day. And that is probably because Tether profits from the waning dominance of the legacy global MoE – the USD.

If bitcoin were only a SoV, nobody would leave their hoard on an exchange, and the trading velocity would be miniscule. But they do. And it isn’t.

Merchants Accept Bitcoin

Some might object that, while bitcoin might be a MoE among the tech boys of the financial cognoscenti, it hasn’t penetrated the “real economy” the way a “real” MoE should. But examples of bitcoin circulating in the real economy would be enough to refute this claim. We’re in luck.

Retailers are using bitcoin as a MoE because it already offers concrete benefits. Take one brilliant example from the recent River report: Atoms, a Brooklyn shoe company. In 2021, Atoms started accepting bitcoin as payment and launched a bitcoin-themed sneaker. Atoms accepts bitcoin as a MoE (consumers pay for shoes with bitcoins), and then Atoms hold it as a SoV until the need arises. And when it does, their SoV bitcoin is automatically tradable MoE bitcoin because it’s the same bitcoin.

Atoms proves that the dichotomy is strictly conceptual and misguided. Actual bitcoin is both a SoV and a MoE; it just depends on how its owner happens to be using it at the moment.

And Atoms is not alone, not by a long shot. Balenciaga accepts bitcoin. Tag Heuer accepts bitcoin. AMC Theatres, PayPal, twitch, Ferrari, and Proton all accept bitcoin. Is anybody going to claim that AMC or PayPal are niche vendors known only to nerds with obscure financial hobbies?

Are these famous, global brands hodling bitcoin as a SoV or trading it as a MoE? There’s that dichotomous thinking again. Bitcoin is a divisible, fungible, durable asset, so they can hold it as long as they want and trade it at any time. They can accept it, spend it, lend it, whatever. Bitcoin has no fundamental essence. It is whatever they/we use it for.

All MoEs and SoVs Are Just Betas

Another major lesson from the examples above is that SoVs and MoEs never stop evolving. Bronze Age fintech was about standardizing ingots and purifying the metals they contained (or, for the ruling class, maybe debasing them). How SoV-MoEs are designed affects how we use them, which influences their design, which affects how we use them, and so on. But evolution is always about local optimization, never perfection, so there will always be room for further improvement.

Good money has always served as both a SoV and a MoE, and bitcoin still has room to grow. Let’s consider the areas where bitcoin could use further optimization.

Fiat’s First-Mover Advantage

If asked, virtually every friend of bitcoin would prefer to receive their income in btc while paying their expenses in fiat. But this doesn’t mean that bitcoin is defective as a MoE; it means that fiat is defective as a SoV. People prefer to hold bitcoin because bitcoin holds its value better than fiat, so it makes sense to save the bitcoin for tomorrow when it will be worth more and spend the fiat today before it’s worth less.

So fiat’s edge is just that it has built up 13 centuries of network effects to compensate for its obvious defects. People know fiat. The world’s payroll systems, tax codes, and banking systems are built around fiat. The world has considerable sunk costs in the fiat project. That’s why it’s so important for bitcoin to exceed fiat in any metric: value retention, autonomy, censorship resistance, and of course…

The UX. Always the UX.

Bitcoin’s UX is improving. Many innovations are unequivocally ameliorations. The Lightning Network, for example, increases bitcoin’s maximum trading velocity by multiple orders of magnitude.

Other aspects of using bitcoin, however, can be features and bugs simultaneously. The most obvious is self-custody. Holding your own bitcoin is really the only way to fully enjoy the autonomy and freedom bitcoin affords, whether as a SoV or a MoE or both. But with great power comes great responsibility, and assessing and implementing different ways to store and use bitcoin can be a bit much for many no-coiners.

And even for all its benefits, Lightning has limitations that we’re still trying to overcome. Lightning adds complexity to liquidity management, although LSPs are helping to transform liquidity from a difficult technical problem into a largely automated financial consideration. But friction is friction.

Similarly, Lightning can only take on new users so fast because each new user requires at least one on-chain transaction and additional liquidity. New technology, like Breez’s nodeless SDK implementation, can improve Lightning’s throughput and mitigate its liquidity constraints just like Lightning surpasses on-chain bitcoin for some use cases.

And if this trend of innovation → UX tweaking → innovation continues as it has for fiat, we’re in good shape. Consider the credit card. Nobody used credit cards for small purchases for the first three decades or so of their existence. It was a big story when Burger King started accepting credit cards in 1993. People even got all judgmental about it. “I think it’s pretty bad if you have to use a credit card when you go to a fast food restaurant.” Credit cards were for big purchases, like airfare, jewelry, hotel stays, and car repairs. In 2024, about a third of payments are made by credit card, and nobody – not a single living soul — cares if you pay for an order of fries or bus fare with a credit card.

People in 1993 react to #creditcards being accepted at a #burgerking

As credit cards became easier to use (it used to be hard work), people used them more and for smaller purchases. The lesson here is that people will use an asset as a MoE selectively if the UX is rocky, using it more frequently and for smaller purchases as the UX improves.

Legal/Regulatory Treatment

We’ve all heard the outdated FUD that bitcoin is basically just for criminals. Proton is a great company that accepts bitcoin and is advised by Sir Tim Berners Lee — not exactly your typical moustache-twirling supervillain. But people fear what they don’t understand, and legislators and regulators love pandering to popular fears.

Some jurisdictions are open and progressive. In the EU, for example, bitcoin is considered a currency and is treated accordingly in most laws. Exchanging bitcoin for another currency incurs no VAT, but buying a product or service with bitcoin does incur VAT, just as it would with any other currency.

In the US, while some regulators and courts have acknowledged that bitcoin is “a medium of exchange and a means of payment,” the IRS treats it as a property subject to capital gains tax, which makes trading it more expensive and, consequently, slows its trading velocity. So it’s natural that bitcoin might look more like a SoV than a MoE to Americans subject to that tax regime.

Some countries like Morocco and China have banned bitcoin outright. Whatever. King Canute tried to stop the tides until his feet got wet, at which point he declared that no king could gainsay eternal laws. That’s a good lesson for the SoV crowd and the staunch bitcoin opponents alike. People want to be free, and they want their money to be free. If you don’t give it to them, they’ll take it eventually.

Volatility

Many people might be averse to using bitcoin as a MoE because of its characteristics as a SoV. First, its price is relatively volatile. In the last few years, we’ve seen the value of bitcoin relative to the USD swing up and down by a factor of 4x. This makes it hard for consumers to spend and hard for retailers to accept because the exchange rate of bitcoin relative to a given good — i.e. its price — can be too uncertain.

The more disposable income and wealth someone has, the less sensitive they are to volatility. If you still have plenty of income left over every month after taxes, groceries, and mortgage payments along with healthy savings, it won’t matter much if one tranche of your portfolio drops a bit for a few months. You use your assets on a different timescale than price volatility. Long-term gains more than outweigh short-term drops, so let it swing.

Many others are not so privileged. Their income is their wealth; they have no savings or surplus to buffer price swings. For them, a sudden drop in the value of their income could mean hungry days at the end of the month. If they obtain bitcoin (and many do), they’re likely to exchange it for a more stable asset as soon as they can.

Bitcoin’s volatility is a boon to some, a curse to others, and irrelevant to many. We can, however, see a natural path forward for it to appeal to all user groups. One way to think about bitcoin’s volatility is as a woefully incomplete index. The value of fiat is usually measured by exchange rates to other currencies, by official “baskets” of goods to determine its official purchasing power parity/consumer price index, and by millions of people just transacting in their everyday lives. Each source of information provides a check on the others, triangulating something like a “true market value.” The more people transact and the more goods are priced in bitcoin, the more precise the triangulation, and the less need for price swings.

In other words, the more people use bitcoin as a MoE, the more its price curve will stabilize relative to other assets. Even as a speculative asset, it would look more like T-Bills than, say, oil. And vibrant use as a MoE will maintain expectations of its future demand, which, along with its deflationary design, preserves bitcoin’s status as an unprecedented SoV. Greater usage just smoothes the upward curve.

Preaching Benefits the Preacher

There’s a bizarre, schoolmarmy undertone in the rants of the SoV proponents. Like, what do they care what we all do with our bitcoin? If SoVs and MoEs necessarily overlap, why lecture everyone that bitcoin is ackchyually a SoV exclusively? Nobody’s hindering their preferred use, so what gives?

Remember the US dollar? The USA convinced the world to go long on the USD. If you convince the world to hoard what you’ve already started hoarding, then you’re in a very good position. You’re stoking demand for what you can supply.

But you don’t even have to supply it. Convincing others to covet your hoard lets you borrow against it, giving you access to leverage. If your hoard grants you these benefits, it can trade at a multiple. If you have n bitcoins in your hoard, you might be able to sell shares of your hoard at a 3n valuation. You’ve just figured out how to push the inflation rate of a deflationary asset up to 300%. Dastardly, but clever.

The beauty of freedom money, though, is that no one can tell you how to use it. Sure, I’m telling you it’s underestimated as a MoE, and I have a vested interest in its use as a MoE, but I’m not telling anyone what to do. I’m describing what I see and debunking some bad, possibly disingenuous claims.

Store your bitcoin where and how you want, spend it where and how you want, and its value depends on what we all do collectively, no what some suits do in their exclusionary conclave. Nor does it depend on what some talking head on twitter said is best. Of course, when the majority of the world’s freedom money is held by a select few, then it won’t be very free.

Bitcoin is flexible enough for all our diverse needs, and we all have a say in what it is and what it will yet become. Let our diversity be our strength.

This is a guest post by Roy Sheinfeld. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.

Source link

You may like

Experts say these 3 altcoins will rally 3,000% soon, and XRP isn’t one of them

Robert Kiyosaki Hints At Economic Depression Ahead, What It Means For BTC?

BNB Steadies Above Support: Will Bullish Momentum Return?

Metaplanet makes largest Bitcoin bet, acquires nearly 620 BTC

Tron’s Justin Sun Offloads 50% ETH Holdings, Ethereum Price Crash Imminent?

Investors bet on this $0.0013 token destined to leave Cardano and Shiba Inu behind

The Islamic conceptualisation of finance is built around a set of core principles which give primacy to honesty, fairness and accountability in trade and transactions. As such, Islamic finance seeks uphold justice, transparency, and shared prosperity in economic systems. Arguably, fiat currency achieves the exact opposite of these principles, since it introduces uncertainty, speculation and inequities that punish the poor, who earn and spend fiat, and favours the rich who invest in assets that benefit from inflation. In this backdrop, Bitcoin emerges as a solution that aligns remarkably well with Islamic finance principles. This article explores why Bitcoin, with its decentralization, transparency, and scarcity, represents the most Islamic form of money, offering transformative potential for the Muslim world.

The foundational principles of Islamic finance include:

1. Prohibition of Riba (Usury):

Interest-based lending, where money generates money without productive activity, is strictly forbidden in Islam. Riba fosters exploitation, concentrates wealth, and undermines social equity.

2. Prohibition of Gharar (Uncertainty):

Transactions should be free from undue speculation or ambiguity. Clear terms and honest practices are paramount.

3. Asset-Backed Economy

Trade and transactions should involve tangible assets or productive activities. Wealth must be earned through legitimate means, not through gambling or speculative bubbles.

4. Risk Sharing

Islamic finance emphasizes equity-based partnerships where profit and loss are shared, ensuring mutual benefit and fairness in all financial dealings.

5. Justice and Equity:

Wealth distribution should serve societal needs, promoting fairness and reducing economic disparities.

One could very credibly argue that the current fiat-based monetary system flagrantly violates these tenets. Central banks set interest rates that underpin the entire fiat system, institutionalizing usury. Money created out of debt inherently generates unearned profits for lenders while indebting others, fostering exploitation and inequality. The fiat system disproportionately benefits those closest to the source of money creation (e.g., banks, governments) at the expense of ordinary people. This “Cantillon Effect” exacerbates wealth inequality, violating Islamic values of equity and justice.

Fiat currencies are prone to inflation and devaluation due to their unlimited supply. This creates uncertainty and speculative behaviour, further destabilizing economies and harming the most vulnerable. Unlike gold or tangible assets, fiat money is not backed by any physical commodity. It is merely a promise of value, eroding trust and violating Islam’s emphasis on tangible, asset-backed wealth. Centralized control of money by a few institutions undermines accountability, fosters corruption, and allows governments to manipulate currencies to serve political agendas, often to the detriment of their citizens. These systemic flaws have led to financial crises, inequality, and the erosion of societal trust.

Bitcoin, the world’s first decentralized digital currency, aligns closely with the ethical and economic teachings of Islam. Bitcoin operates without interest-based mechanisms. Its decentralized nature ensures that no central authority can create money out of thin air or profit unjustly through usury. Every Bitcoin transaction is recorded on an immutable public ledger, the blockchain. This ensures honesty and accountability, eliminating the uncertainty associated with opaque fiat systems.

Bitcoin’s supply is capped at 21 million coins, making it a deflationary asset. Its scarcity mirrors the attributes of gold, historically accepted as sound money in Islamic societies. Unlike fiat money, Bitcoin is not controlled by any government or institution. Its decentralized network empowers individuals and fosters equity, aligning with Islam’s emphasis on justice and fairness.

Bitcoin is not a speculative promise; it is earned through “proof-of-work,” which requires significant energy and computational effort. This tangible cost of production imbues it with intrinsic value, resonating with Islamic financial principles. Bitcoin allows anyone with an internet connection to participate in the global economy. This inclusivity aligns with Islam’s vision of reducing economic barriers and promoting universal access to financial resources. Through its adherence to these principles, Bitcoin offers a viable alternative to the exploitative fiat system, paving the way for a more just and equitable financial future.

Adopting Bitcoin on a wide scale could revolutionize the Muslim world, unlocking unprecedented economic opportunities. Many Muslim-majority countries suffer from chronic inflation, eroding the value of their fiat currencies and impoverishing their citizens. Bitcoin’s deflationary nature provides a hedge against inflation, preserving wealth over time. Millions of Muslims remain unbanked due to lack of access to traditional financial services. Bitcoin’s decentralized system allows individuals to store and transfer wealth securely without relying on banks, fostering economic empowerment. Muslim-majority countries are among the largest recipients of remittances. Bitcoin enables faster, cheaper, and more secure cross-border transactions, reducing reliance on costly intermediaries.

By decentralizing money creation and eliminating the privileges of central banks, Bitcoin ensures a fairer distribution of wealth, addressing economic disparities that plague many Islamic societies. Bitcoin’s transparent system facilitates the development of Shariah-compliant financial products and services, promoting ethical investment opportunities in line with Islamic values. Bitcoin enables nations to reduce their dependence on the US dollar and other foreign currencies, strengthening their economic sovereignty and resilience. By enabling trustless, borderless transactions, Bitcoin fosters trade within the global Muslim community, encouraging innovation and economic integration across nations.

Bitcoin is more than just a technological innovation; it is a financial system rooted in justice, transparency, and equity—values deeply embedded in Islamic teachings. As the Muslim world grapples with the challenges of fiat-based economies, Bitcoin offers a path toward economic independence, financial inclusion, and societal prosperity. By embracing Bitcoin, the Muslim world can align its financial systems with the timeless principles of Islam, paving the way for a fairer and more sustainable future.

This is a guest post by Ghaffar Hussain. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.

Source link

2024 Election

Bitcoin is Neither Racist, Xenophobic, nor Misogynistic: A Response to Ideological Stereotyping

Published

4 weeks agoon

November 27, 2024By

admin

Just hours after the U.S. election results were announced, I received messages from friends filled with striking assumptions. Some congratulated me, mockingly saying, “Congrats, your side won for Bitcoin.” Others expressed disapproval with remarks like, “It’s pathetic!” and “I’m shocked that Americans just voted for Hitler.” One friend said, “You were lucky to find safety in the U.S. as a refugee under Biden’s administration. Refugees and asylum seekers will now face a harder time here, but, hey, it’s still good for your Bitcoin.” Many of these friends work in high-level corporate jobs or are university students.

As a Green Card holder, I was not eligible to vote, but I recognize their huge disappointment in seeing their preferred candidate lose. Their frustrations were directed at me because they know I support Bitcoin and work in the space. I understand that making me a scapegoat says less about me and more about their limited understanding of what Bitcoin’s value represents.

I’m aware that in this highly polarized political landscape, ideological stereotyping becomes evident—not only during election season but also in spaces where innovative thinking should be encouraged. A prime example of this ideological bias occurred during the Ohio State University commencement, where Chris Pan’s speech on Bitcoin was largely booed by students attending their graduation ceremony. I admire the courage it took to stand firm in front of over 60,000 people and continue his speech. My guess is that most of these graduating students have never experienced hyperinflation or grown up under authoritarian regimes, which likely triggered an “auto-reject”’ response to concepts beyond their personal experience.

I’ve encountered similar resistance in my own unfinished academic journey; during my time at Georgetown, I had several unproductive conversations with professors and students who viewed Bitcoin as a far-right tool. Once a professor told me, “Win, just because cryptocurrency (he didn’t use the term Bitcoin) helped you and your people in your home country doesn’t make it a great tool—most people end up getting scammed in America and many parts of the world. I urge you to learn more about it.” The power dynamics in academic settings often discourage open-minded discourse, which is why I eventually refrained from discussing Bitcoin with my professors.

I’ve learned to understand that freedom of expression is a core American value. Yet, I’ve observed that certain demographics or communities label anyone they disagree with as ‘racist.’ In more extreme cases, this reaction can escalate to using influence to have people fired, expelled from school, or subjected to coordinated cyberbullying. I’m not claiming that racism doesn’t exist in American society or elsewhere; I strongly believe both overt and subtle forms of racism still persist and are well alive today.

Although bias and inequality remain widespread, Bitcoin operates on entirely different principles. Bitcoin is borderless, leaderless, and accepting of any nationality or skin color all while without requiring any form of ID to participate. People in war-torn countries convert their savings into Bitcoin to cross borders safely, human rights defenders receive donations in Bitcoin, and women living under the Taliban get paid through the Bitcoin network.

Bitcoin is not racist because it is a tool of empowerment for anyone who is willing to participate. Bitcoin is not Xenophobic because it gives those forced to flee their homes the power to carry their hard-earned economic energy across borders and participate in another economy when every other option is closed. For activists, often branded as ‘criminals’ by authoritarian regimes, it supports them through frozen bank accounts and blocked resources. For women, enduring life under misogynistic rule, Bitcoin offers a rare chance for financial independence.

Going back to the U.S. election context, Bitcoin not only levels the playing field for people in the world’s most forgotten places and darkest corners, but it also opens new avenues for U.S. presidential candidates to engage with this growing community. President-elect Donald Trump has made bold promises regarding Bitcoin, signaling a favorable policy. In contrast, Democratic candidate Vice President Kamala Harris’s campaign reportedly declined to support the Bitcoin community. Grant McCarty, co-founder of the Bitcoin Policy Institute, stated, “Can confirm that the Harris campaign was offered MILLIONS of dollars from companies, PACs, and individuals who were looking for her to simply take meetings with key crypto stakeholders and put together a defined crypto policy plan. The campaign never took the industry seriously.” I believe this is something most people may be unaware of, and confirmation bias often leads to the assumption that all Bitcoin supporters back every policy of the other side, including potential drastic changes to America’s humanitarian commitments such as refugee resettlement and asylum programs, anti-trafficking and protection of vulnerable populations, and foreign aid and disaster relief.

Most people around the world lack a stable economic infrastructure or access to long-term mortgages; they live and earn with currencies more volatile than crypto gambling and, in some cases, holding their own fiat currency is as dangerous as casino chips, or worse.

The Fiat experiment has failed the global majority. I believe that Bitcoin and Bitcoin advocates deserve to be evaluated on their merits and work on global impact, rather than through the binary lens of political bias, misappropriated terms, or factually flawed yet socially accepted diminutive categorizing, which allows them to opt out of learning and evaluating assumptions.

This is a guest post by Win Ko Ko Aung. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.

Source link

Today’s modern Bitcoin exchanges have drastically improved access to Bitcoin ownership in 2024. Gone are the days of janky peer-to-peer (P2P) trade forums and questionably secure early exchanges like Mt Gox. Instead, a legion of Bitcoin on-ramps focused on superior security and user experience (UX) has made purchasing your first Bitcoin a breeze. Many of these services have even embarked on education-focused initiatives to encourage greater adoption during Bitcoin’s most recent bear market. In November 2023 Swan launched Welcome to Bitcoin, their free introductory 1 hour course about Bitcoin. In December 2023, Cash App released BREAD, a free, limited-edition magazine that uses design to tell stories and educate readers about Bitcoin in a relatable and accessible way.

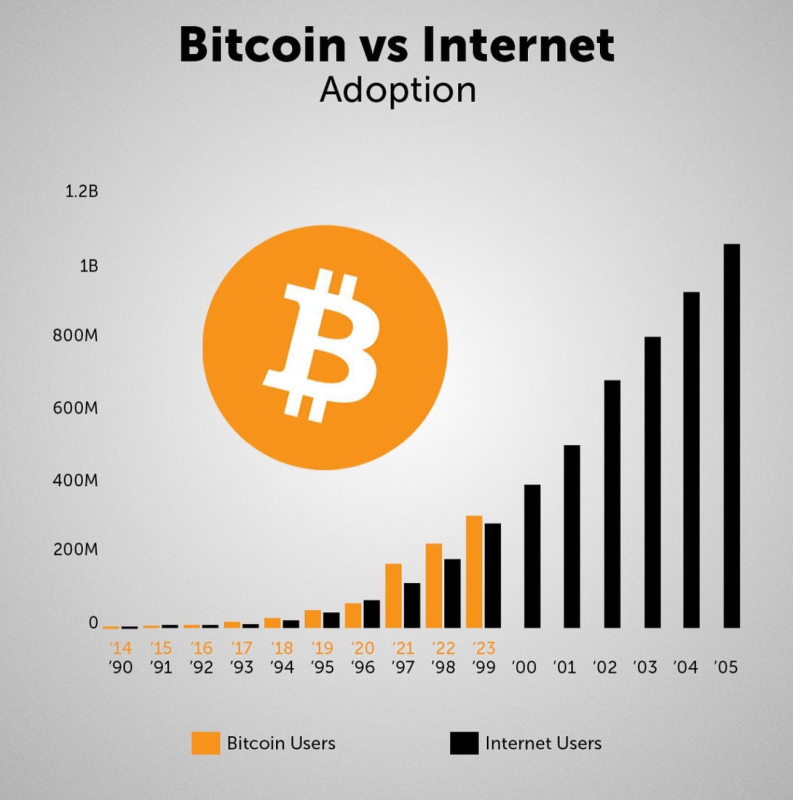

What these initiatives show is that Bitcoin adoption is approaching a turning point. These two major Bitcoin exchanges, along with the industry as a whole, are discovering that easy access to a smash buy button does not guarantee purchase. Numerous barriers to entry still exist for nocoiners, which provide significant constraints to understanding Bitcoin, and thus throttle Bitcoin’s growth and adoption. As we approach a steeper incline in Bitcoin’s bell curve, throwing novices into exchange apps without sufficient education and cultivation is no longer a strategy for success.

What once was a far simpler task of energizing early adopters and cypherpunks around Bitcoin’s clear value proposition, is evolving into a more complex and convoluted process of orange-pilling the early majority of future Bitcoin holders. This, we hope, will then lead to widespread Bitcoin mass adoption as society en masse chooses to store its time and energy in the best money ever created. For this hyperbitcoinization to occur, more people need to understand the intricacies of Bitcoin. This is easier said than done because Bitcoin still has an education problem:

- An Economist Intelligence Unit study reported that 51% of people said a lack of knowledge is the main barrier to Bitcoin ownership.

- A YouGov survey found that 98% of novices don’t understand basic Bitcoin concepts.

- A nationwide survey from the Yale Center discovered that 69% of young people find learning boring.

This research outlines the struggle of onboarding and educating the next generation of Bitcoiners, most notably younger generations who have been shown to possess a limited attention span of 8 seconds. For inspiration to help solve this problem, we can look at one of the most popular mobile games of all time… Pokémon GO.

Pokémon GO was and remains to be, a global phenomenon. This beloved app caught the attention of Gen-Z, millennials, and Gen-X alike, boasting record-breaking engagement stats:

- In 2016, the game peaked at 232 million active players.

- Pokémon GO has grossed over $6 billion in revenue.

- In 2024, 24% of 18–34-year-olds in the US are playing Pokémon GO, while 49% of 35–54 year-olds are playing.

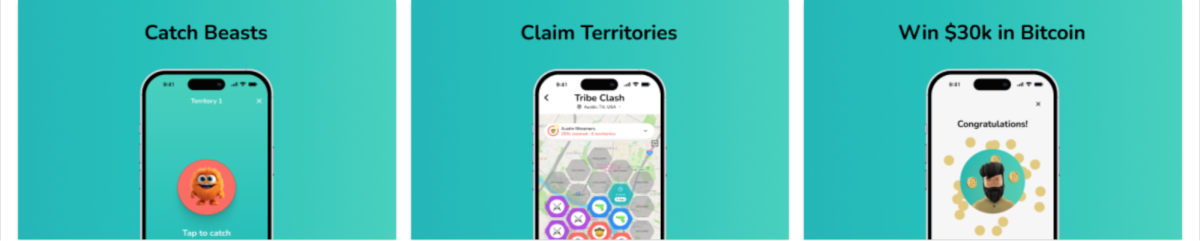

We at Jippi believe that the success of this award-winning game can illuminate the path forward for Bitcoin adoption. So we have set upon the electrifying task of building Tribe Clash–the world’s first Pokémon GO-inspired Bitcoin education game. The rules are simple, create or join a Tribe and battle for dominance over a city with your friends by catching a Bitcoin-themed Beast in every Territory.

Each week Jippi will release a new Territory to be claimed. A Tribe member will explore that Territory with their phone, where they will discover a Bitcoin Beast to catch. If they successfully answer all Bitcoin quiz questions correctly the fastest, they will then catch that beast. The Tribe with the most Territories and Bitcoin Beasts at the end of the game will win $30k worth of Bitcoin to be dispersed equally to each Tribe member.

Our vision is for Jippi to become the largest, most popular platform for beginners to gather, educate, and accumulate Bitcoin. We see Jippi as the most accessible on-ramp into the industry, where we can educate a whole new generation of Bitcoiners from novices to experts by lowering the barrier to entry.

You can support the development of Tribe Clash by contributing to our crowdfunding campaign on Timestamp. Timestamp enables investors of all backgrounds to support Bitcoin-only companies and make an impact. Our campaign is open to both the general public and accredited investors, so we would love for you to join us on this journey.

This is a guest post by Oliver Porter. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.

Source link

Experts say these 3 altcoins will rally 3,000% soon, and XRP isn’t one of them

Robert Kiyosaki Hints At Economic Depression Ahead, What It Means For BTC?

BNB Steadies Above Support: Will Bullish Momentum Return?

Metaplanet makes largest Bitcoin bet, acquires nearly 620 BTC

Tron’s Justin Sun Offloads 50% ETH Holdings, Ethereum Price Crash Imminent?

Investors bet on this $0.0013 token destined to leave Cardano and Shiba Inu behind

End of Altcoin Season? Glassnode Co-Founders Warn Alts in Danger of Lagging Behind After Last Week’s Correction

Can Pi Network Price Triple Before 2024 Ends?

XRP’s $5, $10 goals are trending, but this altcoin with 7,400% potential takes the spotlight

CryptoQuant Hails Binance Reserve Amid High Leverage Trading

Trump Picks Bo Hines to Lead Presidential Crypto Council

The introduction of Hydra could see Cardano surpass Ethereum with 100,000 TPS

Top 4 Altcoins to Hold Before 2025 Alt Season

DeFi Protocol Usual’s Surge Catapults Hashnote’s Tokenized Treasury Over BlackRock’s BUIDL

DOGE & SHIB holders embrace Lightchain AI for its growth and unique sports-crypto vision

182267361726451435

Why Did Trump Change His Mind on Bitcoin?

Top Crypto News Headlines of The Week

New U.S. president must bring clarity to crypto regulation, analyst says

Will XRP Price Defend $0.5 Support If SEC Decides to Appeal?

Bitcoin Open-Source Development Takes The Stage In Nashville

Ethereum, Solana touch key levels as Bitcoin spikes

Bitcoin 20% Surge In 3 Weeks Teases Record-Breaking Potential

Ethereum Crash A Buying Opportunity? This Whale Thinks So

Shiba Inu Price Slips 4% as 3500% Burn Rate Surge Fails to Halt Correction

Washington financial watchdog warns of scam involving fake crypto ‘professors’

‘Hamster Kombat’ Airdrop Delayed as Pre-Market Trading for Telegram Game Expands

Citigroup Executive Steps Down To Explore Crypto

Mostbet Güvenilir Mi – Casino Bonus 2024

NoOnes Bitcoin Philosophy: Everyone Eats

Trending

3 months ago

3 months ago182267361726451435

Donald Trump5 months ago

Donald Trump5 months agoWhy Did Trump Change His Mind on Bitcoin?

24/7 Cryptocurrency News4 months ago

24/7 Cryptocurrency News4 months agoTop Crypto News Headlines of The Week

News4 months ago

News4 months agoNew U.S. president must bring clarity to crypto regulation, analyst says

Price analysis4 months ago

Price analysis4 months agoWill XRP Price Defend $0.5 Support If SEC Decides to Appeal?

Opinion5 months ago

Opinion5 months agoBitcoin Open-Source Development Takes The Stage In Nashville

Bitcoin5 months ago

Bitcoin5 months agoEthereum, Solana touch key levels as Bitcoin spikes

Bitcoin5 months ago

Bitcoin5 months agoBitcoin 20% Surge In 3 Weeks Teases Record-Breaking Potential