Art

Tokenization of the music industry with music NFTs

Published

5 months agoon

By

admin

Disclosure: The views and opinions expressed here belong solely to the author and do not represent the views and opinions of crypto.news’ editorial.

“Party Like It’s 1999,” sang Prince Rogers Nelson, because on June 1, 1999, a new computer software service would forever change how music was distributed, consumed, and even written. Napster was a peer-to-peer file-sharing service that quickly gained popularity among music fans—since its launch in May 1999, it had gathered over 20 million users by March 2000—looking for a way to share and download music online for free. The cataloging software, created by Shawn Fanning and Sean Parker, searched your computer’s hard drive, listed all the MP3 music files contained in it, and allowed anyone else using the service to share and play those files.

Napster’s popularity was short-lived as its ultimate demise resulted from its legal troubles stemming from cybercrime: file sharing and piracy. According to the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), the company’s computer software facilitated copyright infringement and filed a lawsuit against Napster. Napster was ultimately shut down in 2001. Nevertheless, Napster’s technology had a profound impact on the music industry by paving the way for other P2P file-sharing services, which helped to popularize the idea of downloading music online, which gave rise to the concept of the first virtual currency for peer-to-peer systems: Karma. Karma was introduced in 2003 as a way to pay for P2P file-sharing services.

The co-founder of the first internet money—way ahead of Bitcoin (BTC)—was a virtual currency called Karma, designed by Dr. Emin Gun Sirer, who is also the founder and CEO of Ava Labs. Dr. Sirer explained that the emergence of the internet and, subsequently, the World Wide Web marked a pivotal shift from isolated, local computing to global-scale computing:

“Architecturally, we transitioned from standalone computers to a ‘client-server architecture,’ which enabled us to connect to remote services operated by others to leverage their programs and capabilities. This new paradigm gave rise to digital services that catered to the entire world, created millions of jobs, and solidified the U.S.’s position as a global economic leader.”

Dr. Sirer added, “I built a system called Karma for ensuring that people who participate in peer-to-peer file sharing networks don’t just leech. They don’t just take resources from the network, but they also donate resources. So everybody was downloading files, nobody was putting up files for upload. And so my solution to this was, what if there was some magic Internet money that nobody controlled that you needed to use to download files? And if you ran out of it, then that would put an end to your leeching ways and you would now put up some files to get your Karma back.”

Ava Labs is a software company founded in 2018 that is headquartered in Brooklyn, New York, whose mission is to tokenize the world’s assets on the Avalanche public blockchain and other blockchain ecosystems. This includes tokenizing the music industry with music NFTs.

Dr. Sirer explains that blockchains represent the next phase in the evolution of networked computer systems by facilitating many-to-many communication over a shared ledger. This allows multiple computers to collaborate, achieve consensus, act in unison, and build shared services in the network. In turn, this enables the development of unique, secure tokenized assets, such as music NFTs, among many other innovative applications.

By harnessing the power of blockchain technology, which records the copyrights to ownership of the music that cannot be changed, the Avaissance program music NFTs give musicians a new universe of creative and financial options. They expand the range of music they can make by allowing them to sell music NFTs directly to fans via an NFT marketplace. Dr. Sirer points out that there are different types of tokens.

A real-world asset

A token can be the direct or indirect representation of a traditional asset. For example, numerous musicians are currently publishing complete songs and albums as music NFTs or selling their fans NFT concert tickets. While music NFTs offer exciting opportunities for artists, they raise copyright and intellectual property concerns. When artists tokenize their music, they must ensure they have the right to do so. Smart contracts, a key component of music NFTs, automate the payment of royalties to creators each time their tokenized music is resold. This feature is a game-changer in an industry where musicians often lose out on resale profits. Smart contracts simplify the process of compensating musicians, but it also raises questions about how different types of music royalties should be calculated and distributed fairly.

A virtual item

A token can represent a piece of digital art, including a musician’s album cover, poster, and show photographs; a collectible in the form of a musician’s autograph; a gaming skin; videos of virtual concerts or tracks; virtual artist meet and greet experiences; and more. These digital assets can be tokenized into music NFTs to be traded for a profit. These can be varied in function and form as well. They can range from simple non-programmable pictures of the musician, a common use of NFTs, to complex assets, some used in virtual concerts, that can encode all sorts of functions and features of the asset directly inside the asset itself.

Pay-for-use

Public blockchains constitute shared computing resources that must be allocated efficiently. A token is the perfect mechanism to meter resource consumption and prioritize important activities. Such tokens are sometimes known as “gas tokens.” For example, BTC is the gas token of the Bitcoin blockchain, ETH for Ethereum, AVAX for Avalanche, and so on. Without gas or transaction costs, a single user or small group of users could potentially overwhelm the blockchain, similar to a denial of service attack, making the blockchain unusable.

Sebastien Borget, COO and co-founder of The Sandbox, a culture and entertainment platform based on the Ethereum network, explained that he established a new web3 arena for musical entertainment in the metaverse called ShowCity that is home to The Voice and other TV shows. ShowCity is also home to music industry heavyweights such as Snoop Dog, Steve Aoki, Chainsmokers, and Warner Music Group—the first major music firm to enter into the metaverse with its top recording artists like Bruno Mars, Twenty-One Pilots, Ed Sheeran, Madonna, Metallica to hold virtual concerts and other musical experiences.

ShowCity offers musicians exclusive digital and physical perks—such as tickets to live tapings of The Voice—if they purchase a LAND in ShowCity in exchange for The Sandbox (SAND), which was deemed a security by the US Securities and Exchange Commission last year.

Musicians create avatars, digital versions of themselves, to hold virtual concerts, selling millions of dollars in tickets and NFT merchandise. All items acquired in The Sandbox are 100% owned by the musicians themselves, creating revenue opportunities.

Sebastien Borget indicated that ShowCity brings the open metaverse one step forward in the direction of sustainable fan-owned and community-driven musical entertainment initiatives with its partnerships with non-profit foundations supporting social, environmental, and climate causes.

As musicians are turning to tokenization of their music, holding metaverse concerts, issuing collectible NFTs, and collectors are investing in music NFTs, they should bear in mind that the tokenization of the music industry comes with potential legal challenges and financial quagmires. These include issues concerning copyright, taxation, security classification of gas tokens, AML concerns for metaverse land sales, sanctions compliance, artist royalty, environmental footprint challenges to music NFT and metaverse platforms, and other matters that could complicate the music NFT landscape.

Jonathan Cutler, senior manager at Washington National Tax, Deloitte Tax LLP, said that,

“The final digital asset reporting regulations, published at the end of June, keep NFTs in scope for Form 1099-DA reporting. The rules include a reporting threshold of $600 for sales of ‘specified’ NFTs—NFTs that are indivisible, unique, and do not reference certain excluded property. Where sales exceed $600, a digital asset broker may report the NFT sales on a single Form 1099-DA for the year rather than separate forms for each sale. These regulations make no comment on treatment of certain NFTs as collectibles for tax purposes. The April draft Form 1099-DA, which is pending redraft for the final rules, also included no reference to collectibles.”

Source link

You may like

BNB Steadies Above Support: Will Bullish Momentum Return?

Metaplanet makes largest Bitcoin bet, acquires nearly 620 BTC

Tron’s Justin Sun Offloads 50% ETH Holdings, Ethereum Price Crash Imminent?

Investors bet on this $0.0013 token destined to leave Cardano and Shiba Inu behind

End of Altcoin Season? Glassnode Co-Founders Warn Alts in Danger of Lagging Behind After Last Week’s Correction

Can Pi Network Price Triple Before 2024 Ends?

Art

Crypto Entrepreneur Justin Sun Ate a $6.2M Banana Artwork at an Event in Hong Kong

Published

3 weeks agoon

November 30, 2024By

adminJustin Sun walked into the room flanked by his usual entourage of bodyguards and advisers and made his way to the stage. Behind him, a banana was duct taped in position on a white wall. On either side, two blank-faced men in white shirts and black aprons stared into the sea of cameras and smartphones. I wondered what they were thinking.

As for what I was thinking, it was something along the lines of how ridiculous this all was. To give some background, on Nov. 21 Tron founder Justin Sun paid a whopping $6.2 million — including $1 million in commission — at an auction at Sotheby’s in New York for an artwork called Comedian. The work, created by modern artist Maurizio Cattelan in 2019, is the aforementioned banana duct taped to the wall.

The reaction among many observers was the typical one seen whenever anyone spends a large sum of money on modern art: bewilderment, a bit of disgust, an eye roll. I think people who don’t like art can still appreciate the skill that goes into paintings or sculptures. If works like Comedian or Unmade Bed have any artistic merit, I cannot comprehend it. Tron’s public relations team assured me art is subjective.

But it’s memecoin season and things with absolutely no intrinsic value are very in right now. So it was hardly surprising that shortly after buying the banana-and-duct-tape combo, Sun said he planned to eat it.

This has happened twice before: Once in 2019, when a performance artist took it from the Art Basel in Miami shortly after it was sold for $120,000. Then again by a South Korean art student at the Leeum Museum of Art in Seoul in 2023.

It doesn’t affect the artwork. The banana and duct tape are replaced regularly anyway.

The consumption took place at the 5-star Peninsula Hotel in the Tsim Sha Tsui area of Hong Kong on Friday, a stone’s throw from some of the city’s most notorious doss houses.

The crowd consisted of a mix of journalists and people from the art and crypto industries, Tron and Sotheby’s employees and so-called key opinion leaders (KOLs). I mean the sort of people who wear clothes that look like they came from the local market, but probably cost thousands of dollars — U.S. dollars, not Hong Kong. One fellow journalist had flown all the way from Shanghai just for the event. Around us in the foyer, servers in white suit jackets served wine and other refreshments.

An information board near the entrance said Sun sought to immerse himself in the performance art of Cattelan, with Comedian as his muse. “He envisions this iconic piece as a catalyst for sparking dialogues and exchanges,” the text read.

Other people I spoke to in attendance were more skeptical, characterizing the event as little more than a marketing gimmick.

It’s not the first time Sun has courted the limelight. In 2019, he paid $4.57 million at a charity auction to have lunch with Warren Buffett. In April this year, he commissioned a theme song for Tron written by legendary movie composer Hans Zimmer.

He also served as Grenada’s permanent representative to the World Trade Organization and, more recently, became prime minister of the libertarian micronation Liberland, which is located in a floodplain on the Croatian side of the Danube.

Sun has also made the headlines in far less whimsical ways. Last year the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission charged him with fraud and other securities law violations, including “fraudulently manipulating the secondary market for TRX through extensive wash trading.” Sun responded on X that the suit was without merit.

Meanwhile, his lawyers have threatened media outlets with legal action when they report on Tron’s use by terrorist groups.

Perhaps the hope was that the banana would bring everyone together and let them forget about this. Indeed, Sun seems to believe the banana is the start of some sort of mass movement. “Is it simply a banana or something belonging to all of us?” he asked at one point.

He compared the process of replacing the banana every few days to the changing Chinese dynasties over the millennia. He praised the banana for how much traffic and attention it had brought himself and Tron. He noted that the banana’s value went beyond the limits of money.

Then he ate it.

November in Hong Kong seems to just be the prime season for odd crypto events. Fortunately, unlike ApeFest last November, this time nobody was hospitalized. Instead, upon leaving attendees received a replica of Comedian along with a roll of duct tape and a spare banana.

At least that’s my breakfast tomorrow sorted.

Source link

Art

How To Paint a Sandwich: A Solo Presentation On Memes And Digital Culture By Nardo At Bitcoin MENA

Published

1 month agoon

November 18, 2024By

admin

In anticipation of a solo exhibition by artist Nardo at Bitcoin Mena, in collaboration with AOTM Gallery, I sat down with him to explore the intersections of memes, mythologies, and digital culture. Nardo’s work navigates the intriguing space between the tangible form of traditional painting and the fleeting nature of meme culture—two seemingly contrasting mediums that are evolving in tandem with Bitcoin.

The title of your exhibition, Fresh Impact, and the centerpiece painting, Sandwich Artist, both reference Subway-related memes. Notably, Subway became the first fast-food chain to accept bitcoin in 2013—a moment documented by Andrew Torba, who famously used bitcoin to buy a $5 sub in Allentown, Pennsylvania (an ironic detail, given that Torba is now CEO of the social network Gab). This early mix of Bitcoin and meme culture sparked humorous reflections on “spending generational wealth” on footlongs and highlighted themes of currency value over time, as the dollar’s purchasing power wanes while bitcoin’s grows. How does this Subway meme resonate with you, and how does it shape your approach to painting in an increasingly digital age?

I think there is something to be said about quick consumption in contemporary culture—whether it’s fast food footlong subs or internet memes. The attention span of human senses has diminished to bursts of repeated dopamine, where selecting your type of bread, meats, and toppings becomes the most exciting part of your afternoon. Then comes the tireless effort of finishing 12 inches of processed food matter. You repeat this over and over because it’s convenient, and maybe next time, you’ll excite yourself by swapping cheddar for provolone.

However, Subway has developed a systematic experience that feels eternal. Memes and internet behavior function in a similar way. The ephemeral consumption of entertaining or humorous memes acts as the dopamine hit—we share them with friends, they spread at rapid speeds, and then they often die off, leading us to move on to the next. Yet, the success of memes also lies in their systems: cultural iconography, bold fonts superimposed onto captivating imagery, hyper-sharpened visuals, deep-fried aesthetics, or low effort applications. Memes rely on visual and cultural layers—bread, meat, and toppings.

I think, as it relates to Bitcoin, we should really confront its experiential nature in the exact moment of exchange. To have purchased a footlong for $5 worth of Bitcoin in 2013, only to view it today in 2024 as ~$4,300, is both absurd and somewhat painful—but the experience is eternal. The very act of using digital internet money in exchange for physical, consumable goods feels almost alchemical.

Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins coined the term “memes” to describe units of cultural transmission, likening their spread to gene replication. Memes also resemble viruses in how they propagate through social networks, blurring the lines between genes and viruses as both can integrate into DNA and influence evolution. You and I have joked that memes—and memecoins—are akin to the fast food of digital culture, serving as cybernetic junk food or street drugs. Do you consider memes to be a low art form? Is the buildup of studio trash made famous by painter Francis Bacon or the outlandish waste and detritus of Dash Snow’s 2007 “hamster nest” installation somehow related? What are your thoughts on contemporary artists like Christine Wang, who replicates notable memes in her recent painting exhibition, “Cryptofire Degen,” at The Hole in New York? What happens when a digital meme becomes a physical painting?

This all ties back to what I discussed earlier—I am interested in slowing down the process of consumption. To meticulously hand-paint a meme in oil and present it as such can be a little jarring. Similarly, considering trash as form or content, rather than something to be discarded, fascinates me.

After the user has consumed their lunch and doom-scrolled through countless memes on Twitter, what remains as the detritus of all that? The whole experience can feel like nullifying brain rot—a diminishing of structure and existence within passive chaos. Perhaps, though, that is the liminal mindset necessary to birth the most viral ideas.

My introduction to cybernetics came from Japanese animation series like Ghost in the Shell (1995-2014), which explore cyberpunk themes such as internet-connected minds, hackers, and cyber viruses, echoing Dawkins’ ideas about memes and cultural transmission. The series highlights concepts like “ghost-hacking” and “thought viruses,” which replicate across networks and influence societal behavior, aligning with Dawkins’ notion of self-replicating cultural units. Given your recent exploration of the “skibidi toilet” meme phenomenon, what insights have you gained about how this meme has propagated across social networks and shaped the collective consciousness of younger audiences?

The Ghost in the Shell connection isn’t far removed from the world as we know it now. Much like the premise of that “fiction,” our fleshy brains are nestled within a cybernetic façade of digital personas and communications. We practically live vicariously through a digitized shadow-self—a projection of what we think we could become. This aligns with why I often say, “You become what you meme.”

I am deeply intrigued by the phenomenon of American youth becoming obsessed with new memes that older generations are unable to compute, such as Skibidi Toilet. I think it is in this fracturing of sensibility that new languages are born, while old mythologies are repackaged in contemporary ways. Skibidi Toilet is the Iliad of the Internet.

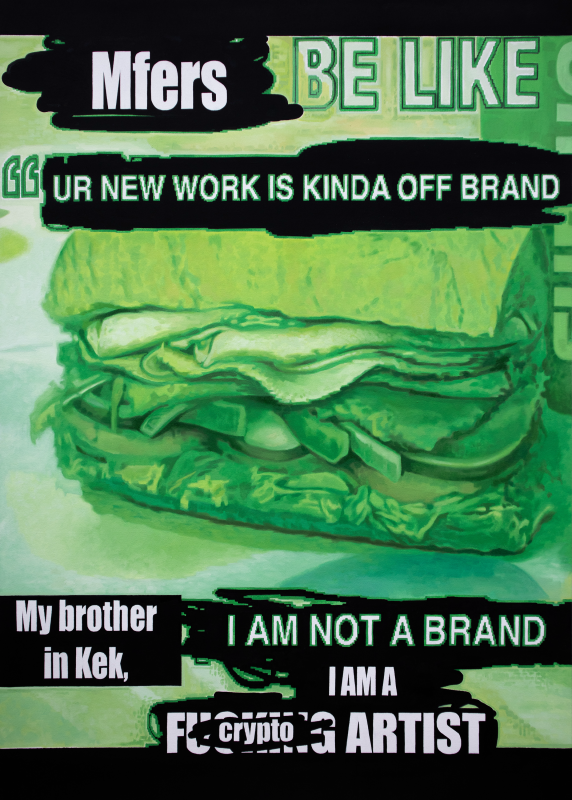

Beyond Ghost in the Shell’s exploration of cybernetics, the seminal anime series Neon Genesis Evangelion intersects with the Age of Aquarius concept through its themes of interconnectedness and collective consciousness. The series delves into the merging of individual identities, echoing how “hive mind” behaviors in contemporary internet culture reflect the rapid influence of shared information and memes. In your artwork Sandwich Artist, you highlight the tension between individual artistry and the pressures of representing a faceless brand. How have you observed this shift over time, and how can artists engage with collective ideas while preserving their individuality in today’s digital culture?

The Sandwich Artist piece utilizes a well-known meme template, yet through various digital alterations—specifically the literal scribbling out of pre-existing text—it takes on the feel of graffiti and eventually becomes my own. I like this piece for how it represents an individual manifesto of my work and reflects how I think about my artistry as a whole. Sure, consistent branding and aesthetics are great for sales if done right, but I’m more interested in how my work exists within a long enough historical timeline. The hive mind desires a brand to rally behind, yet history yearns for individual artistry.

We’ve discussed the term “subway” in relation to submarine sandwiches, but it also evokes the idea of underground transportation. Japan famously studied mycelial growth patterns to optimize its subway and train systems. Similar to fungi, memes propagate and connect individuals in a vast, decentralized network, evolving as they move from one “host” to another. This fungal comparision highlights how memes adapt and spread dynamically, mirroring natural systems of growth and communication. How do you think artists can consciously navigate this memetic landscape of propagation, host vessels, and network dynamics?

The lifespan of most internet memes moves so rapidly that it’s difficult to grasp them before they vanish into a shallow grave. Among the few that manage to take hold of the collective consciousness, I find it fascinating to analyze how they connect to humanity’s past on a metaphysical level. Trends and symbols have remained consistent throughout human history; they simply resurface in different forms as time passes.

Efficient memes rely on efficient systems for delivering information. As artists, we should remain conscious of history and metaphysical symbolism, as this awareness can help us uncover our own primordial self through the mirror of memes.

Source link

Art

Art Under Surveillance: Ripcache’s Radical Take at Bitcoin Amsterdam

Published

2 months agoon

October 15, 2024By

admin

Ripcache, a pseudonymous artist, explores themes of surveillance and privacy through a 1-bit pixelated aesthetic. By examining the impact of modern surveillance in centralized and decentralized systems, Ripcache’s work examines trade-offs of the advancing digital age. Their recent series, “Hyperscalers,” was featured on the main stage at Bitcoin Amsterdam, with a private sale facilitated by UTXO Management’s OTC desk to collector Brissi, marking a key milestone in their career and the greater ordinals ecosystem.

We sat down with Ripcache to discuss his art.

Ordinals on Bitcoin create new ways for audiences to engage with digital art. In a world increasingly dominated by surveillance, how does this impact your views on ownership, visibility, and control over art?

Ordinals challenge the status quo about ownership and control. In a way, they democratize access to certain forms of art. In the past, a lot of the art world has been about exclusivity. Artwork hidden away in private collections or in storage, accessible only to a select few. This exclusivity is like a centralized database with limited entry.

In contrast, inscribing art on bitcoin makes it universally accessible. Sure, you still might not own it, but at least anyone with an internet connection can look at it and verify the work without intermediaries. This accessibility and transparency challenges traditional power structures in art ownership and curation. With that said, in an era of pervasive surveillance, this openness also raises questions around privacy and the potential for art and provenance to be co-opted or misused. It’s a delicate balance between visibility and control and advocating for a future where art is both accessible and respectful of individual privacy (for the artist, collector and wider public).

As technologies like blockchain and AI continue to shape the future of digital art, how do you see the relationship between art and surveillance evolving? Could AI offer an alternative narrative to the surveillance-heavy world we inhabit, or only deepen it?

AI and blockchain are actively reshaping our perceptions of surveillance and privacy. While AI does have immense creative potential, in that it can enable new forms of creation and interaction, it also poses risks. The biggest risk is amplifying surveillance capabilities by collecting and processing vast amounts of data, predicting behaviors, and potentially stifling spontaneity.

It’s tough to say definitively, however. AI could deepen the surveillance state but it also has the potential to offer alternatives. Artists already use AI to explore themes of privacy and identity, reclaiming some control over the narrative. And maybe it’s a bit cliche, but I think crypto and bitcoin provide a counterbalance by enabling decentralized and increasingly more anon interactions. With ordinals, artists can share their work with collectors all over the world without centralized oversight, promoting a culture of openness while safeguarding individual freedoms. As this tech evolves, I think it’s crucial that we actively shape them to enhance rather than diminish our creative and personal liberties.

Incorporating motifs like CCTV and drones into your work raises questions about the tension between the peer-to-peer aspect of Bitcoin and the omnipresence of surveillance. Are you concerned that systems meant to decentralize power may still be co-opted by regulatory forces or contribute to an increasingly digital panopticon?

The risk of decentralized systems being co-opted is a real concern. My use of motifs like closed-circuit TV cameras and drones is an attempt to highlight this tension. These symbols represent the watchful eyes of surveillance, prompting viewers to consider how technologies intended for empowerment can be repurposed for control.

Financial transparency on bitcoin is empowering. It has the potential to hold institutions accountable, but it can also expose personal data if not carefully managed. There’s a paradox where increased openness can lead to decreased individual privacy. To prevent decentralization from contributing to a digital panopticon, it’s important to advocate for technologies that prioritize user privacy, like zero-knowledge proofs, and to stay vigilant about regulatory developments.

Art can play a role in this discourse by bringing these issues to the cultural forefront and by encouraging proactive engagement with the cypherpunk ethos as well as the second and third order implications of technology.

Source link

BNB Steadies Above Support: Will Bullish Momentum Return?

Metaplanet makes largest Bitcoin bet, acquires nearly 620 BTC

Tron’s Justin Sun Offloads 50% ETH Holdings, Ethereum Price Crash Imminent?

Investors bet on this $0.0013 token destined to leave Cardano and Shiba Inu behind

End of Altcoin Season? Glassnode Co-Founders Warn Alts in Danger of Lagging Behind After Last Week’s Correction

Can Pi Network Price Triple Before 2024 Ends?

XRP’s $5, $10 goals are trending, but this altcoin with 7,400% potential takes the spotlight

CryptoQuant Hails Binance Reserve Amid High Leverage Trading

Trump Picks Bo Hines to Lead Presidential Crypto Council

The introduction of Hydra could see Cardano surpass Ethereum with 100,000 TPS

Top 4 Altcoins to Hold Before 2025 Alt Season

DeFi Protocol Usual’s Surge Catapults Hashnote’s Tokenized Treasury Over BlackRock’s BUIDL

DOGE & SHIB holders embrace Lightchain AI for its growth and unique sports-crypto vision

Will Shiba Inu Price Hold Critical Support Amid Market Volatility?

Chainlink price double bottoms as whales accumulate

182267361726451435

Why Did Trump Change His Mind on Bitcoin?

Top Crypto News Headlines of The Week

New U.S. president must bring clarity to crypto regulation, analyst says

Will XRP Price Defend $0.5 Support If SEC Decides to Appeal?

Bitcoin Open-Source Development Takes The Stage In Nashville

Ethereum, Solana touch key levels as Bitcoin spikes

Bitcoin 20% Surge In 3 Weeks Teases Record-Breaking Potential

Ethereum Crash A Buying Opportunity? This Whale Thinks So

Shiba Inu Price Slips 4% as 3500% Burn Rate Surge Fails to Halt Correction

Washington financial watchdog warns of scam involving fake crypto ‘professors’

‘Hamster Kombat’ Airdrop Delayed as Pre-Market Trading for Telegram Game Expands

Citigroup Executive Steps Down To Explore Crypto

Mostbet Güvenilir Mi – Casino Bonus 2024

NoOnes Bitcoin Philosophy: Everyone Eats

Trending

3 months ago

3 months ago182267361726451435

Donald Trump5 months ago

Donald Trump5 months agoWhy Did Trump Change His Mind on Bitcoin?

24/7 Cryptocurrency News4 months ago

24/7 Cryptocurrency News4 months agoTop Crypto News Headlines of The Week

News4 months ago

News4 months agoNew U.S. president must bring clarity to crypto regulation, analyst says

Price analysis4 months ago

Price analysis4 months agoWill XRP Price Defend $0.5 Support If SEC Decides to Appeal?

Opinion5 months ago

Opinion5 months agoBitcoin Open-Source Development Takes The Stage In Nashville

Bitcoin5 months ago

Bitcoin5 months agoEthereum, Solana touch key levels as Bitcoin spikes

Bitcoin5 months ago

Bitcoin5 months agoBitcoin 20% Surge In 3 Weeks Teases Record-Breaking Potential