Culture

What Does Bitcoin Mean to You? An Interview with Marco Santini

Published

5 months agoon

By

admin

In a collaboration merging the worlds of art and Bitcoin, Marco Santini – an acclaimed impact artist – recently lent his creativity to Bitcoin Magazine and The Bitcoin Conference. His involvement began with creating a piece with Bitcoin Magazine’s very first issue, Illuminated: Bitcoin Magazine Issue #1 (see here), which was notably purchased by Emily Bailey at a Sotheby’s auction and now proudly resides in The Bitcoin Museum in Nashville, TN. This iconic piece features key elements that encapsulate Bitcoin’s pivotal moments in history from the magazine itself.

At the 2024 Bitcoin Conference, Santini took his engagement a step further by creating a live mural and collaborative activation. This vibrant piece, now also displayed in The Bitcoin Museum, aims to encapsulate the diverse voices of attendees who answered the profound question: “What does Bitcoin mean to you?” A notable response came from BTC Inc’s CEO, David Bailey, who reflected, “You know, so many things, cliché cheesy ones like ‘hope,’ but I’m gonna say ‘prosperity.’ Because Bitcoin, beyond hope, you need all the things that Bitcoin brings to give your life…fulfillment beyond just the financial element of it. If you’re full of hope, potential, and [are] excited about the future, you’ll prosper.”

Tony Sakich had the opportunity to interview Santini and delve deeper into his conference experience and the essence of his mural:

—

Tony: OK, so you’ve been doing this all day? What is your response to everyone that has said things to you and came up and asked you to write words? What’s been your experience at the conference?

Marco: Sure. My name is Marco Santini. I’m an impact artist. I travel around the world and I like to say that I mirror the spirit of communities through interactive collaborative art. This weekend here at the Bitcoin Conference, I was asking people, “What does Bitcoin mean to you?” No judgment, no fear, listening to everyone, all different walks of life, and really trying to understand what they think.

We got over 250 unique answers that I’ve captured here into this mural. It really has bright colors and positive messaging. I believe that surrounding yourself with bright colors and a lot of messaging can help your mental health and make you feel better and just kind of overall connect yourself to the community.

Tony: What were some of the interesting takeaways from the responses you received?

Marco: Specifically, there are a few interesting takeaways. By far, the most responded answer was “freedom.” A lot of people talked about being able to own their own money, not having an intermediary, maybe fear or distrust of the system in the banks. The second biggest idea was this idea of community, that people feel they are part of a family, their friends are here. They kind of interact with each other and look forward to seeing each other in person. It was really interesting to hear how people connect and find friends and meet people here. Even though they’re wearing Bitcoin logos head to toe, when I asked them, “What does Bitcoin mean?” they’d stop and really think about it, often leading to deep, meaningful conversations.

Tony: That sounds awesome. Can I add one more?

Marco: What is your word?

Tony: P2P, peer-to-peer. Because Bitcoin is for the people and it is a way that anyone can transact whenever they want freely. They don’t need anyone’s permission to send anything. It’s all about community and trusting the person that you are doing business with.

—

Santini’s mural is not just a collection of words but a vivid tapestry that captures the hopes, dreams, and realities of the Bitcoin community. The art piece is a reflection of the decentralized ethos of Bitcoin, emphasizing freedom, community, and peer-to-peer interactions.

David Bailey’s contribution to the mural, highlighting “prosperity,” resonates deeply within the Bitcoin community. His perspective underscores the multifaceted nature of Bitcoin as not just a financial tool but a beacon of hope and a catalyst for personal and communal growth.

Santini’s art continues to inspire and connect people, reflecting the ever-growing and evolving spirit of the Bitcoin community. The mural, now part of the Bitcoin Museum, stands as a testament to the power of collaborative art and the profound impact of Bitcoin on individuals’ lives. Visitors to the museum can witness firsthand the colorful expressions of what Bitcoin means to people from all walks of life, providing a unique and enriching experience that goes beyond traditional exhibits.

See more from Marco Santini on X: @MarcoSantiniArt and on Instagram: @_Marco_Santini

Source link

You may like

Experts say these 3 altcoins will rally 3,000% soon, and XRP isn’t one of them

Robert Kiyosaki Hints At Economic Depression Ahead, What It Means For BTC?

BNB Steadies Above Support: Will Bullish Momentum Return?

Metaplanet makes largest Bitcoin bet, acquires nearly 620 BTC

Tron’s Justin Sun Offloads 50% ETH Holdings, Ethereum Price Crash Imminent?

Investors bet on this $0.0013 token destined to leave Cardano and Shiba Inu behind

The Islamic conceptualisation of finance is built around a set of core principles which give primacy to honesty, fairness and accountability in trade and transactions. As such, Islamic finance seeks uphold justice, transparency, and shared prosperity in economic systems. Arguably, fiat currency achieves the exact opposite of these principles, since it introduces uncertainty, speculation and inequities that punish the poor, who earn and spend fiat, and favours the rich who invest in assets that benefit from inflation. In this backdrop, Bitcoin emerges as a solution that aligns remarkably well with Islamic finance principles. This article explores why Bitcoin, with its decentralization, transparency, and scarcity, represents the most Islamic form of money, offering transformative potential for the Muslim world.

The foundational principles of Islamic finance include:

1. Prohibition of Riba (Usury):

Interest-based lending, where money generates money without productive activity, is strictly forbidden in Islam. Riba fosters exploitation, concentrates wealth, and undermines social equity.

2. Prohibition of Gharar (Uncertainty):

Transactions should be free from undue speculation or ambiguity. Clear terms and honest practices are paramount.

3. Asset-Backed Economy

Trade and transactions should involve tangible assets or productive activities. Wealth must be earned through legitimate means, not through gambling or speculative bubbles.

4. Risk Sharing

Islamic finance emphasizes equity-based partnerships where profit and loss are shared, ensuring mutual benefit and fairness in all financial dealings.

5. Justice and Equity:

Wealth distribution should serve societal needs, promoting fairness and reducing economic disparities.

One could very credibly argue that the current fiat-based monetary system flagrantly violates these tenets. Central banks set interest rates that underpin the entire fiat system, institutionalizing usury. Money created out of debt inherently generates unearned profits for lenders while indebting others, fostering exploitation and inequality. The fiat system disproportionately benefits those closest to the source of money creation (e.g., banks, governments) at the expense of ordinary people. This “Cantillon Effect” exacerbates wealth inequality, violating Islamic values of equity and justice.

Fiat currencies are prone to inflation and devaluation due to their unlimited supply. This creates uncertainty and speculative behaviour, further destabilizing economies and harming the most vulnerable. Unlike gold or tangible assets, fiat money is not backed by any physical commodity. It is merely a promise of value, eroding trust and violating Islam’s emphasis on tangible, asset-backed wealth. Centralized control of money by a few institutions undermines accountability, fosters corruption, and allows governments to manipulate currencies to serve political agendas, often to the detriment of their citizens. These systemic flaws have led to financial crises, inequality, and the erosion of societal trust.

Bitcoin, the world’s first decentralized digital currency, aligns closely with the ethical and economic teachings of Islam. Bitcoin operates without interest-based mechanisms. Its decentralized nature ensures that no central authority can create money out of thin air or profit unjustly through usury. Every Bitcoin transaction is recorded on an immutable public ledger, the blockchain. This ensures honesty and accountability, eliminating the uncertainty associated with opaque fiat systems.

Bitcoin’s supply is capped at 21 million coins, making it a deflationary asset. Its scarcity mirrors the attributes of gold, historically accepted as sound money in Islamic societies. Unlike fiat money, Bitcoin is not controlled by any government or institution. Its decentralized network empowers individuals and fosters equity, aligning with Islam’s emphasis on justice and fairness.

Bitcoin is not a speculative promise; it is earned through “proof-of-work,” which requires significant energy and computational effort. This tangible cost of production imbues it with intrinsic value, resonating with Islamic financial principles. Bitcoin allows anyone with an internet connection to participate in the global economy. This inclusivity aligns with Islam’s vision of reducing economic barriers and promoting universal access to financial resources. Through its adherence to these principles, Bitcoin offers a viable alternative to the exploitative fiat system, paving the way for a more just and equitable financial future.

Adopting Bitcoin on a wide scale could revolutionize the Muslim world, unlocking unprecedented economic opportunities. Many Muslim-majority countries suffer from chronic inflation, eroding the value of their fiat currencies and impoverishing their citizens. Bitcoin’s deflationary nature provides a hedge against inflation, preserving wealth over time. Millions of Muslims remain unbanked due to lack of access to traditional financial services. Bitcoin’s decentralized system allows individuals to store and transfer wealth securely without relying on banks, fostering economic empowerment. Muslim-majority countries are among the largest recipients of remittances. Bitcoin enables faster, cheaper, and more secure cross-border transactions, reducing reliance on costly intermediaries.

By decentralizing money creation and eliminating the privileges of central banks, Bitcoin ensures a fairer distribution of wealth, addressing economic disparities that plague many Islamic societies. Bitcoin’s transparent system facilitates the development of Shariah-compliant financial products and services, promoting ethical investment opportunities in line with Islamic values. Bitcoin enables nations to reduce their dependence on the US dollar and other foreign currencies, strengthening their economic sovereignty and resilience. By enabling trustless, borderless transactions, Bitcoin fosters trade within the global Muslim community, encouraging innovation and economic integration across nations.

Bitcoin is more than just a technological innovation; it is a financial system rooted in justice, transparency, and equity—values deeply embedded in Islamic teachings. As the Muslim world grapples with the challenges of fiat-based economies, Bitcoin offers a path toward economic independence, financial inclusion, and societal prosperity. By embracing Bitcoin, the Muslim world can align its financial systems with the timeless principles of Islam, paving the way for a fairer and more sustainable future.

This is a guest post by Ghaffar Hussain. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.

Source link

2024 Election

Bitcoin is Neither Racist, Xenophobic, nor Misogynistic: A Response to Ideological Stereotyping

Published

4 weeks agoon

November 27, 2024By

admin

Just hours after the U.S. election results were announced, I received messages from friends filled with striking assumptions. Some congratulated me, mockingly saying, “Congrats, your side won for Bitcoin.” Others expressed disapproval with remarks like, “It’s pathetic!” and “I’m shocked that Americans just voted for Hitler.” One friend said, “You were lucky to find safety in the U.S. as a refugee under Biden’s administration. Refugees and asylum seekers will now face a harder time here, but, hey, it’s still good for your Bitcoin.” Many of these friends work in high-level corporate jobs or are university students.

As a Green Card holder, I was not eligible to vote, but I recognize their huge disappointment in seeing their preferred candidate lose. Their frustrations were directed at me because they know I support Bitcoin and work in the space. I understand that making me a scapegoat says less about me and more about their limited understanding of what Bitcoin’s value represents.

I’m aware that in this highly polarized political landscape, ideological stereotyping becomes evident—not only during election season but also in spaces where innovative thinking should be encouraged. A prime example of this ideological bias occurred during the Ohio State University commencement, where Chris Pan’s speech on Bitcoin was largely booed by students attending their graduation ceremony. I admire the courage it took to stand firm in front of over 60,000 people and continue his speech. My guess is that most of these graduating students have never experienced hyperinflation or grown up under authoritarian regimes, which likely triggered an “auto-reject”’ response to concepts beyond their personal experience.

I’ve encountered similar resistance in my own unfinished academic journey; during my time at Georgetown, I had several unproductive conversations with professors and students who viewed Bitcoin as a far-right tool. Once a professor told me, “Win, just because cryptocurrency (he didn’t use the term Bitcoin) helped you and your people in your home country doesn’t make it a great tool—most people end up getting scammed in America and many parts of the world. I urge you to learn more about it.” The power dynamics in academic settings often discourage open-minded discourse, which is why I eventually refrained from discussing Bitcoin with my professors.

I’ve learned to understand that freedom of expression is a core American value. Yet, I’ve observed that certain demographics or communities label anyone they disagree with as ‘racist.’ In more extreme cases, this reaction can escalate to using influence to have people fired, expelled from school, or subjected to coordinated cyberbullying. I’m not claiming that racism doesn’t exist in American society or elsewhere; I strongly believe both overt and subtle forms of racism still persist and are well alive today.

Although bias and inequality remain widespread, Bitcoin operates on entirely different principles. Bitcoin is borderless, leaderless, and accepting of any nationality or skin color all while without requiring any form of ID to participate. People in war-torn countries convert their savings into Bitcoin to cross borders safely, human rights defenders receive donations in Bitcoin, and women living under the Taliban get paid through the Bitcoin network.

Bitcoin is not racist because it is a tool of empowerment for anyone who is willing to participate. Bitcoin is not Xenophobic because it gives those forced to flee their homes the power to carry their hard-earned economic energy across borders and participate in another economy when every other option is closed. For activists, often branded as ‘criminals’ by authoritarian regimes, it supports them through frozen bank accounts and blocked resources. For women, enduring life under misogynistic rule, Bitcoin offers a rare chance for financial independence.

Going back to the U.S. election context, Bitcoin not only levels the playing field for people in the world’s most forgotten places and darkest corners, but it also opens new avenues for U.S. presidential candidates to engage with this growing community. President-elect Donald Trump has made bold promises regarding Bitcoin, signaling a favorable policy. In contrast, Democratic candidate Vice President Kamala Harris’s campaign reportedly declined to support the Bitcoin community. Grant McCarty, co-founder of the Bitcoin Policy Institute, stated, “Can confirm that the Harris campaign was offered MILLIONS of dollars from companies, PACs, and individuals who were looking for her to simply take meetings with key crypto stakeholders and put together a defined crypto policy plan. The campaign never took the industry seriously.” I believe this is something most people may be unaware of, and confirmation bias often leads to the assumption that all Bitcoin supporters back every policy of the other side, including potential drastic changes to America’s humanitarian commitments such as refugee resettlement and asylum programs, anti-trafficking and protection of vulnerable populations, and foreign aid and disaster relief.

Most people around the world lack a stable economic infrastructure or access to long-term mortgages; they live and earn with currencies more volatile than crypto gambling and, in some cases, holding their own fiat currency is as dangerous as casino chips, or worse.

The Fiat experiment has failed the global majority. I believe that Bitcoin and Bitcoin advocates deserve to be evaluated on their merits and work on global impact, rather than through the binary lens of political bias, misappropriated terms, or factually flawed yet socially accepted diminutive categorizing, which allows them to opt out of learning and evaluating assumptions.

This is a guest post by Win Ko Ko Aung. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.

Source link

Today’s modern Bitcoin exchanges have drastically improved access to Bitcoin ownership in 2024. Gone are the days of janky peer-to-peer (P2P) trade forums and questionably secure early exchanges like Mt Gox. Instead, a legion of Bitcoin on-ramps focused on superior security and user experience (UX) has made purchasing your first Bitcoin a breeze. Many of these services have even embarked on education-focused initiatives to encourage greater adoption during Bitcoin’s most recent bear market. In November 2023 Swan launched Welcome to Bitcoin, their free introductory 1 hour course about Bitcoin. In December 2023, Cash App released BREAD, a free, limited-edition magazine that uses design to tell stories and educate readers about Bitcoin in a relatable and accessible way.

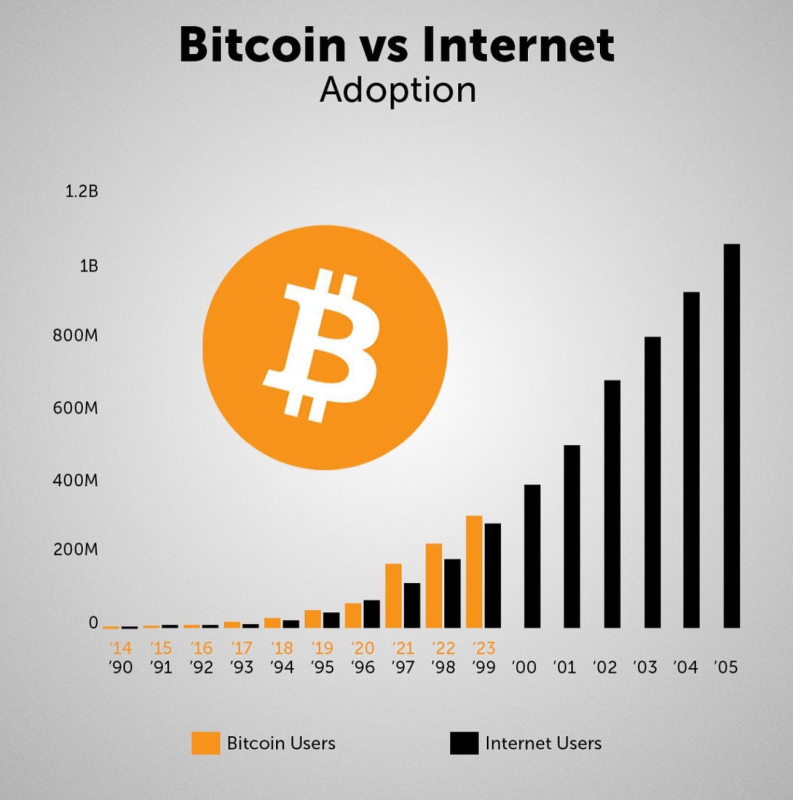

What these initiatives show is that Bitcoin adoption is approaching a turning point. These two major Bitcoin exchanges, along with the industry as a whole, are discovering that easy access to a smash buy button does not guarantee purchase. Numerous barriers to entry still exist for nocoiners, which provide significant constraints to understanding Bitcoin, and thus throttle Bitcoin’s growth and adoption. As we approach a steeper incline in Bitcoin’s bell curve, throwing novices into exchange apps without sufficient education and cultivation is no longer a strategy for success.

What once was a far simpler task of energizing early adopters and cypherpunks around Bitcoin’s clear value proposition, is evolving into a more complex and convoluted process of orange-pilling the early majority of future Bitcoin holders. This, we hope, will then lead to widespread Bitcoin mass adoption as society en masse chooses to store its time and energy in the best money ever created. For this hyperbitcoinization to occur, more people need to understand the intricacies of Bitcoin. This is easier said than done because Bitcoin still has an education problem:

- An Economist Intelligence Unit study reported that 51% of people said a lack of knowledge is the main barrier to Bitcoin ownership.

- A YouGov survey found that 98% of novices don’t understand basic Bitcoin concepts.

- A nationwide survey from the Yale Center discovered that 69% of young people find learning boring.

This research outlines the struggle of onboarding and educating the next generation of Bitcoiners, most notably younger generations who have been shown to possess a limited attention span of 8 seconds. For inspiration to help solve this problem, we can look at one of the most popular mobile games of all time… Pokémon GO.

Pokémon GO was and remains to be, a global phenomenon. This beloved app caught the attention of Gen-Z, millennials, and Gen-X alike, boasting record-breaking engagement stats:

- In 2016, the game peaked at 232 million active players.

- Pokémon GO has grossed over $6 billion in revenue.

- In 2024, 24% of 18–34-year-olds in the US are playing Pokémon GO, while 49% of 35–54 year-olds are playing.

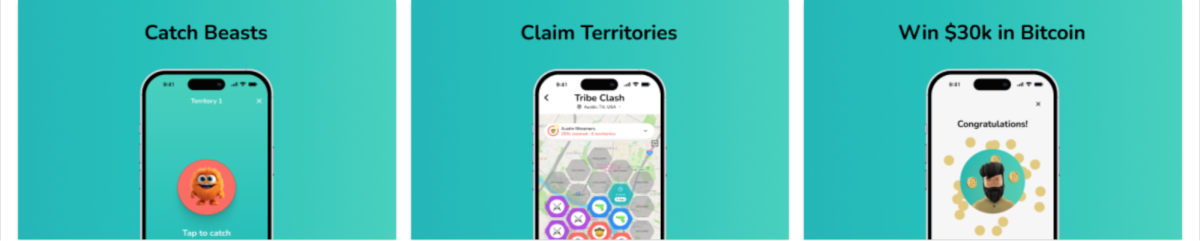

We at Jippi believe that the success of this award-winning game can illuminate the path forward for Bitcoin adoption. So we have set upon the electrifying task of building Tribe Clash–the world’s first Pokémon GO-inspired Bitcoin education game. The rules are simple, create or join a Tribe and battle for dominance over a city with your friends by catching a Bitcoin-themed Beast in every Territory.

Each week Jippi will release a new Territory to be claimed. A Tribe member will explore that Territory with their phone, where they will discover a Bitcoin Beast to catch. If they successfully answer all Bitcoin quiz questions correctly the fastest, they will then catch that beast. The Tribe with the most Territories and Bitcoin Beasts at the end of the game will win $30k worth of Bitcoin to be dispersed equally to each Tribe member.

Our vision is for Jippi to become the largest, most popular platform for beginners to gather, educate, and accumulate Bitcoin. We see Jippi as the most accessible on-ramp into the industry, where we can educate a whole new generation of Bitcoiners from novices to experts by lowering the barrier to entry.

You can support the development of Tribe Clash by contributing to our crowdfunding campaign on Timestamp. Timestamp enables investors of all backgrounds to support Bitcoin-only companies and make an impact. Our campaign is open to both the general public and accredited investors, so we would love for you to join us on this journey.

This is a guest post by Oliver Porter. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.

Source link

Experts say these 3 altcoins will rally 3,000% soon, and XRP isn’t one of them

Robert Kiyosaki Hints At Economic Depression Ahead, What It Means For BTC?

BNB Steadies Above Support: Will Bullish Momentum Return?

Metaplanet makes largest Bitcoin bet, acquires nearly 620 BTC

Tron’s Justin Sun Offloads 50% ETH Holdings, Ethereum Price Crash Imminent?

Investors bet on this $0.0013 token destined to leave Cardano and Shiba Inu behind

End of Altcoin Season? Glassnode Co-Founders Warn Alts in Danger of Lagging Behind After Last Week’s Correction

Can Pi Network Price Triple Before 2024 Ends?

XRP’s $5, $10 goals are trending, but this altcoin with 7,400% potential takes the spotlight

CryptoQuant Hails Binance Reserve Amid High Leverage Trading

Trump Picks Bo Hines to Lead Presidential Crypto Council

The introduction of Hydra could see Cardano surpass Ethereum with 100,000 TPS

Top 4 Altcoins to Hold Before 2025 Alt Season

DeFi Protocol Usual’s Surge Catapults Hashnote’s Tokenized Treasury Over BlackRock’s BUIDL

DOGE & SHIB holders embrace Lightchain AI for its growth and unique sports-crypto vision

182267361726451435

Why Did Trump Change His Mind on Bitcoin?

Top Crypto News Headlines of The Week

New U.S. president must bring clarity to crypto regulation, analyst says

Will XRP Price Defend $0.5 Support If SEC Decides to Appeal?

Bitcoin Open-Source Development Takes The Stage In Nashville

Ethereum, Solana touch key levels as Bitcoin spikes

Bitcoin 20% Surge In 3 Weeks Teases Record-Breaking Potential

Ethereum Crash A Buying Opportunity? This Whale Thinks So

Shiba Inu Price Slips 4% as 3500% Burn Rate Surge Fails to Halt Correction

Washington financial watchdog warns of scam involving fake crypto ‘professors’

‘Hamster Kombat’ Airdrop Delayed as Pre-Market Trading for Telegram Game Expands

Citigroup Executive Steps Down To Explore Crypto

Mostbet Güvenilir Mi – Casino Bonus 2024

NoOnes Bitcoin Philosophy: Everyone Eats

Trending

3 months ago

3 months ago182267361726451435

Donald Trump5 months ago

Donald Trump5 months agoWhy Did Trump Change His Mind on Bitcoin?

24/7 Cryptocurrency News4 months ago

24/7 Cryptocurrency News4 months agoTop Crypto News Headlines of The Week

News4 months ago

News4 months agoNew U.S. president must bring clarity to crypto regulation, analyst says

Price analysis4 months ago

Price analysis4 months agoWill XRP Price Defend $0.5 Support If SEC Decides to Appeal?

Opinion5 months ago

Opinion5 months agoBitcoin Open-Source Development Takes The Stage In Nashville

Bitcoin5 months ago

Bitcoin5 months agoEthereum, Solana touch key levels as Bitcoin spikes

Bitcoin5 months ago

Bitcoin5 months agoBitcoin 20% Surge In 3 Weeks Teases Record-Breaking Potential