Opinion

Bitcoin Season Two Proposals Facing Early Headwinds

Published

6 days agoon

By

admin

If you haven’t been around too long, it’s hard to fully appreciate how quickly narratives can shift in this industry, especially when playing catch-up. Fads grow old, memes become tired. It’s fair to say that this year’s seasonal craze is currently feeling the pressure of Bitcoin’s fading momentum.

While it could be easy to write it off as a temporary setback caused by the usual bull market correction, strong underlying currents are working against popular scaling narratives. As this tide is going out, it’s become a little hard to ignore those out there swimming naked.

Is the airdrop meta over?

If it wasn’t clear already, the recent crop of projects proposing to “build on Bitcoin” has so far been more about opportunism than innovation. Yes, BitVM and ordinals sparked genuine interest and creativity but the follow-through leaves a lot to be desired. This has been caused, in large part, by lazy operators. In lieu of doing actual engineering work, every other third-rate entrepreneur in the industry simply took the Ethereum playbook and ran with it on Bitcoin.

I made a case in my last article for why this modular cottage industry has left Ethereum worse for wear from a scaling standpoint but recent developments have highlighted just how misaligned the economic incentives are.

Of course, the impediment to this infrastructure arms race has been the ability of its promoters to print tokens like it’s going out of style. Unfortunately for them, it does look like the trend is beginning to buckle on those schemes. You might remember how everyone eventually pivoted away from ICOs after Dentacoin raised billions of dollars. Something similar is playing out as we speak.

Just a couple of months ago, I explained how the notion of points had conquered the token airdrop meta. Alternative execution layers were popping out left and right, advertising the opportunity to collect eventual rewards in exchange for liquidity on their networks. The premise was simple enough: users would be incentivized to use applications on a given rollup or contribute assets to its trading pools. Once the chain would launch, tokens would be allocated to a semi-random set of qualified participants. The idea was that this would further align them with the protocol and its future.

It turns out the exact opposite is playing out. Over the last week, a couple of heavily anticipated token airdrops shined light on the absurdity of the method.

How do you verify the identity of a user in a pseudonymous system? You can’t. The inability to do so creates an opportunity for any capable actor to impersonate any number of users. Unsurprisingly, well-capitalized actors quickly caught on to the trick and have been very busy exploiting it to their benefit. Instead of users, airdrops have attracted mercenaries who are pillaging every new layer they can get their wallets on.

You might be wondering why I’m writing about tokens in a Bitcoin article. Consider it only a reminder that any Bitcoin scaling proposal or layer that involves a token should be avoided at all costs. Putting aside the fraudulent nature of the assets, this playbook is a telltale sign of projects that are behind the curve, even by Ethereum standards. I don’t care what technology they claim to work on nor should you care about their execution environment or zero-knowledge proof. The window is closing in on them and we can expect them to shortchange their “users” at every turn to profit from whatever liquidity this racket has left. Stay away.

Ethereum’s identity crisis

The Bitcoinlayers platform reported yesterday that more than half of current scaling proposals for Bitcoin were planning on using Ethereum’s EVM as a technology platform. I do not know what to make of this number. It’s probably generous to associate any of those with Bitcoin but the market is clearly interested in exploring this idea.

This is especially telling considering the volatile state of Ethereum at the moment. Don’t call it a civil war yet but some battle lines are being drawn and the outcome will be telling for its rollup-centric roadmap. I previously laid out the case for Ethereum’s network fragmentation. Suffice it to say that things are escalating quickly and the project is again facing serious debates and introspection.

On one hand, a cohort of developers are advocating for the enshrinement of rollup operations into the protocol to consolidate economic activity and improve user experience. Another group is raising questions about the initiative claiming it would further centralize MEV extraction and affect censorship resistance. It’s increasingly looking like Vitalik might need to pull another rabbit out of his hat.

Combined with fatigue over the commoditization of EVM execution environments, the previously celebrated modular thesis is starting to look rather tenuous. At the very least, the original playbook does not seem to hold anymore and the narratives are shifting again.

The timing of this could be better for emerging Bitcoin layers who are starting to look pretty outdated by industry standards — and they haven’t launched yet!

Memetic exhaustion

You would never catch me being bearish on memes but they do move in cycles and the latest iteration has lost some of its luster. While I’m not ready to call the top of this new meme paradigm, it’s another example of new Bitcoin layers being late to the show. Without dog and cat tokens, what market exists for all the infrastructure being built?

The ground is shifting beneath the feet of a new generation of Bitcoin builders. I suspect those who decided to take the longer road of putting in actual work will have a better shot at making it to the other end of this bull market. Doing so will require learning valuable lessons from the experiments playing out on the other sides of the pond. It would appear patience is warranted given the quickly evolving state of affairs.

Source link

You may like

Taliban jailed 8 traders for holding and using crypto

Solana Struggles to Rise Amid Bitcoin Price Uncertainty

Developing in Web 3.0 Is on the Cusp of a Breakthrough

Digital Shovel Sues RK Mission Critical for Patent Infringement on Bitcoin Mining Containers

crypto will get positive regulation ‘no matter who wins’ election

Toncoin (TON) v Cardano (ADA): On-chain Data Show Gains

Financial Surveillance

How Financial Surveillance Threatens Our Democracies: Part 2

Published

8 hours agoon

July 3, 2024By

admin

Undemonstrated Effectiveness and Efficiency

I’m not aware of any study establishing the effectiveness of KYC measures in combating money laundering. And it’s not for lack of searching.

Conversely, there are numerous studies tending to conclude the opposite. Ronald Pol, a researcher at La Trobe University in Melbourne, synthesized in a research paper published in 2020, many works: Anand 2011; Brzoska 2016; Chaikin 2009; Ferwerda 2009; Findley, Nielson, and Sharman 2014; Harvey 2008; Levi 2002, 2012; Levi and Maguire 2004; Levi and Reuter 2006, 2009; Naylor 2005; Pol 2018b; Reuter and Truman 2004; Rider 2002a, 2002b, 2004; Sharman 2011; van Duyne 2003, 2011; Verhage 2017.

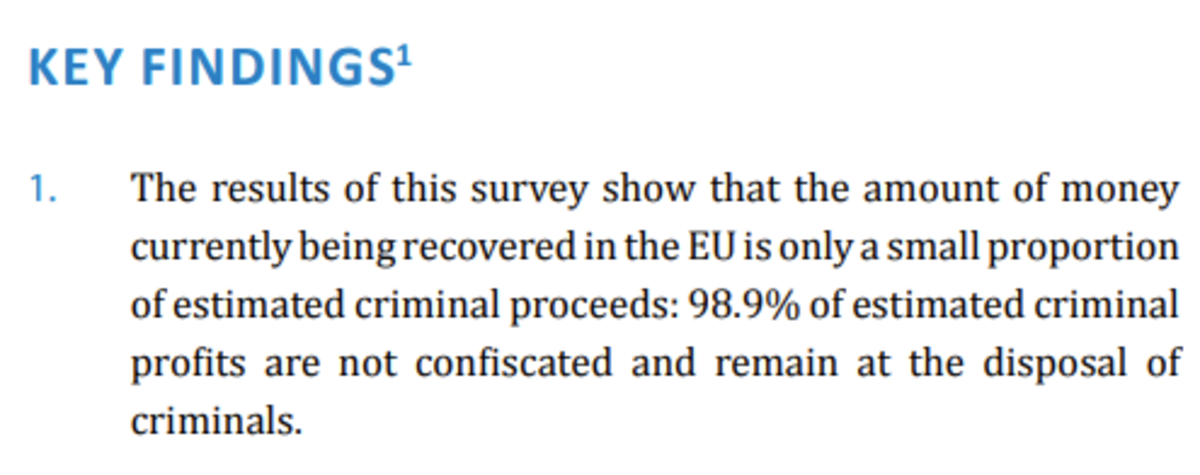

The main finding of this research paper is captured in a more than eloquent title: “Money Laundering Control: The Least Effective Public Policy in the World?”

What do we learn?

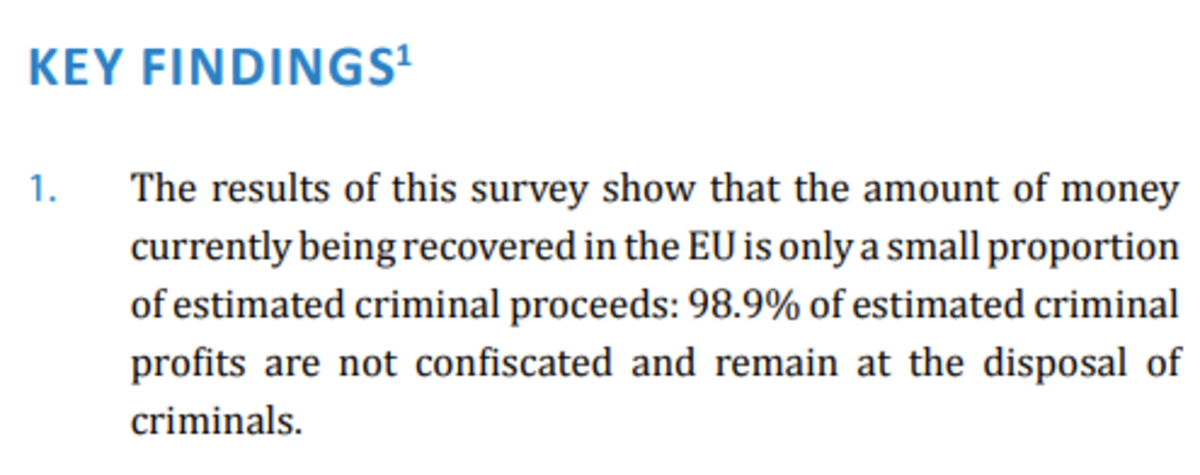

That KYC and AML procedures allow the recovery of approximately 0.05% of global criminal money, meaning $1.5 billion out of the $3 trillion in crime money circulating worldwide each year. And this is assuming that 50% of the recovered money is through these procedures, whereas an empirical study in New Zealand showed a different reality, where 80% of seizures were made through conventional means, and only 20% through KYC and AML procedures.

The author of the paper summarizes it as follows: “if the impact of three decades of money laundering controls barely registers as a rounding error in criminal accounts and “Criminals, Inc” keep up to 99.95 percent of the earnings from misery, and reasonable prospects for better outcomes remain persistently unexplored, the harsh reality is that the current policy prescription inadvertently protects, supports and enables much of the serious profit-motivated crime that it seeks to counter. In any event, the anti-money laundering experiment remains a viable candidate for the title of least effective policy initiative, ever, anywhere (Cassara 2017, 2).”

A Europol study in 201636 yields similar figures: criminals would retain nearly 99% of their profits.

That’s effectiveness covered.

What about efficiency, meaning what resources are mobilized to achieve this result?

The answer is once again confusing.

Studies vary widely in estimating the compliance costs imposed on businesses, particularly financial ones, ranging in 2018 from $304 billion annually according to LexisNexis, to $1.28 trillion according to Thomson Reuters37, without even considering the costs imposed on states and public services, as well as indirect costs (productivity losses, frictions, etc.).

Even by a low estimate, for every euro extracted from crime, 200€ were spent. The situation is so absurd in Europe that compliance costs (€144 billion) exceed the total money (€110 billion) generated by crime each year!

Faced with such poor results and the magnitude of their costs, any sensible person or company would take some time to reflect on the sustainability of such a system. But we are dealing with a religion here, and asking for evidence and reasoning can make one suspect of complicity with money laundering and terrorism.

This industry has also become extremely lucrative for a range of actors who have developed a wide range of services: compliance-specialized lawyers, consulting firms, as well as startups offering dedicated tools, even named RegTech. Interestingly enough, with nearly $4.3 billion in penalties imposed on financial institutions in 2018, and $8.1 billion in 2019, the business also proves lucrative for states, which earn more in fines than they recover from criminals…

Totalitarian regimes dreamed of it, liberal democracies did it: financial surveillance and its consequences

With the imposition of these procedures on the financial system, new or existing risks take on major proportions.

The first is censorship, linked to the drastic reduction of online anonymity. The second is arbitrariness in the application of decisions and sanctions. The third is the theft of sensitive information.

Financial censorship as a political weapon for democratic asphyxiation

The risk of censorship is often perceived as a distant problem in Western democracies. And yet, living in a democracy does not prevent the temptation of censorship that prevails in human beings, and examples abound.

The Democracy Index published by the British newspaper The Economist ranks Canada 13th, the United Kingdom 18th, South Korea 22nd. All are classified as “full democracies,” ahead of France (23rd). India, the world’s largest democracy, ranks 41st, not far from our Belgian (36th) or Italian (34th) neighbors.

And yet, these countries have a story to tell about censorship related to customer knowledge procedures and KYC.

In Canada, for example, as recently as 2022, as truckers’ protests intensified, the Ontario government and then the Canadian government declared a state of emergency and imposed financial coercion measures on the protest movement, bypassing the usual democratic and legal processes. It was the first time in Canadian history that such a state of emergency was imposed.

Under the pretext of wanting to know the origin of the funds financing the crowdfunding campaigns supporting the movement, the financial surveillance agency (FINTRAC) was involved. The two financial platforms GoFundMe and GiveSendGo were forced to freeze the funds. Even more worrying, the Canadian government invoked its emergency powers to freeze the individual accounts of nearly a hundred people involved in the protests. A real financial suffocation under a political pretext.

Whether one agrees or disagrees with the reasons behind the protests is besides the point. This state of emergency would later be deemed unconstitutional by the Federal Court of Canada in January 202438. But the damage is done: the protest has ceased, protesters have been financially choked, the rule of law and individual freedoms have been diminished.

In the United Kingdom, another case made headlines and caused quite a scandal: that of Nigel Farage. This Brexit supporter and leader, a client of the same bank for 43 years, announced in 2023 on Twitter39 that his accounts had been closed without explanation. Two days later, as the scandal erupted in the UK, he announced that his requests to open accounts had been rejected by 9 banks, under the pretext that he is a “politically exposed person,” a PEP, an acronym created by these customer knowledge regulations. However, other political decision-makers do not face the same problems in opening or maintaining bank accounts, raising questions about differential treatment based on political opinions.

The incident caused a stir in the UK, and the BBC confirmed that the account had been closed for political reasons40. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak had to address the issue41 and summoned the country’s major banks to ensure their respect of freedom of expression.

Even more recently in India, at the end of March 2024, the influence of the banking sector on the finances of economic actors was materialized into the country’s politics, enabling the ruling party to financially suffocate its rival, the Indian National Congress, the former party of Gandhi.

As the Human Rights Foundation recalls in its 17th Financial Freedom Report newsletter42, “The Indian government, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, froze the bank accounts of its largest political opposition party, the Indian National Congress (INC), citing allegations of tax evasion, just weeks before the upcoming election. According to INC statements on X43, ‘all our bank accounts have been frozen. We cannot carry out our campaign work. We cannot support our workers and candidates. Our leaders cannot travel across the country.’ A few days later, the Indian agency for fighting financial crime also arrested opposition leader Arvind Kejriwal44 in what is seen as a broader move to eliminate competition in the upcoming elections. These events highlight the growing need for a neutral and apolitical currency as a tool of democratic activism and for political campaigns.”

It is tempting to think that such things “do not happen here.” But the examples I have deliberately cited are democracies, most of which are better ranked in this regard than France.

And France has already shifted on similar issues.

An unfair system : selective enforcement of measures

Identity collection and counter-terrorism efforts in areas outside of finance have also shown that they can be widely diverted from their original purpose. One notable example is South Korea, the first country to attempt to combat anonymity on the internet, enacting a law in 2008 requiring identity collection by social networks to combat hate speech and misinformation.

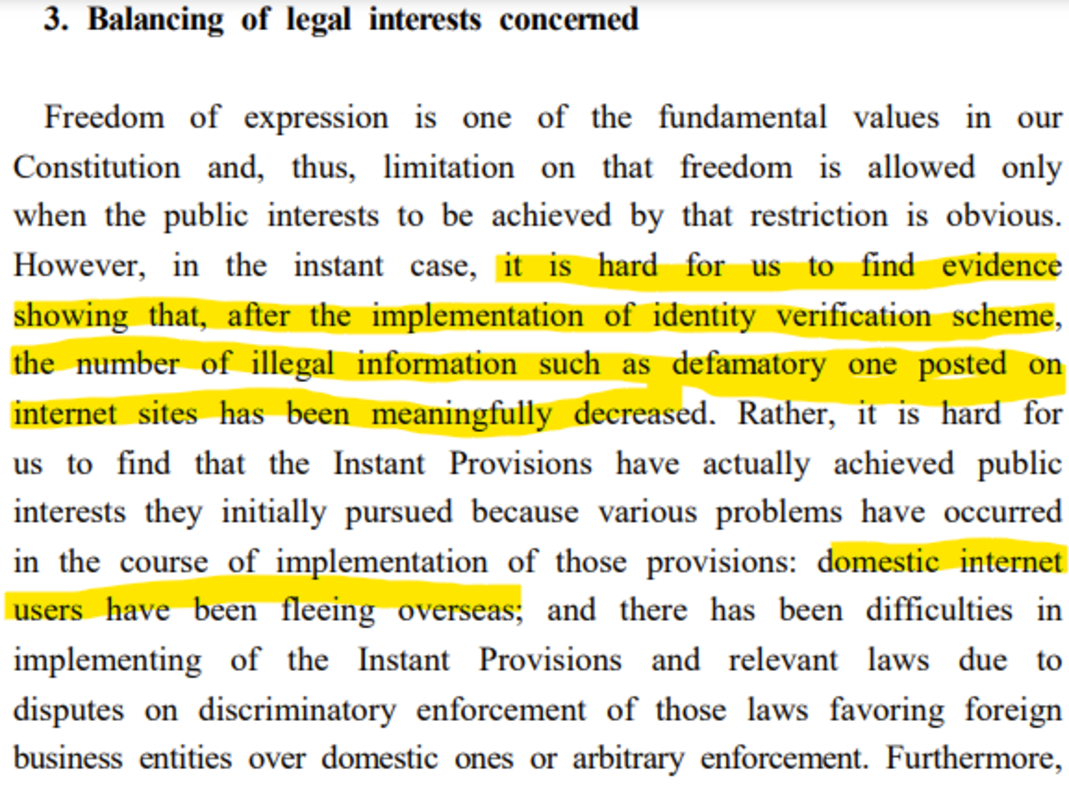

In 2012, the Constitutional Court of South Korea abolished the law45, deeming it unconstitutional. It regretfully noted numerous pitfalls: the selective and arbitrary application of this law due to its overly vague criteria, the lack of evidence showing that the law’s enforcement had reduced the quantity of illegal content posted online, and the stifling of local economic actors, who had to comply with costly standards, to the benefit of foreign actors who continued to operate in the country, attracting South Korean internet users concerned with their ability to express themselves freely.

The Court concluded by affirming that identity collection had “a chilling effect on people’s expression of opinion itself,” which constitutes “an obstacle to the free formation of public opinions — a basis for democratic society.”

One doesn’t need to go to Asia to see the danger posed by this censorship and laws aimed at combating terrorism.

In France, certain political groups, especially on the left, had a rude awakening when, after supporting various laws aimed at limiting hate speech and the glorification of terrorism, they are now targeted for “eco-terrorism” or “promotion of terrorism.” The fight against terrorism often serves as a convenient pretext to restrict the expression of legitimate political opposition, which is serious and damaging in a democracy, in which the ability to disagree with the majority opinion must absolutely be preserved.

In this regard, the parallel with the identity collection by financial institutions is striking: no evidence of their effectiveness, drastic economic standards leading to sector concentration and benefiting foreign actors, and selective enforcement by authorities of the prosecutions to be initiated, among other things.

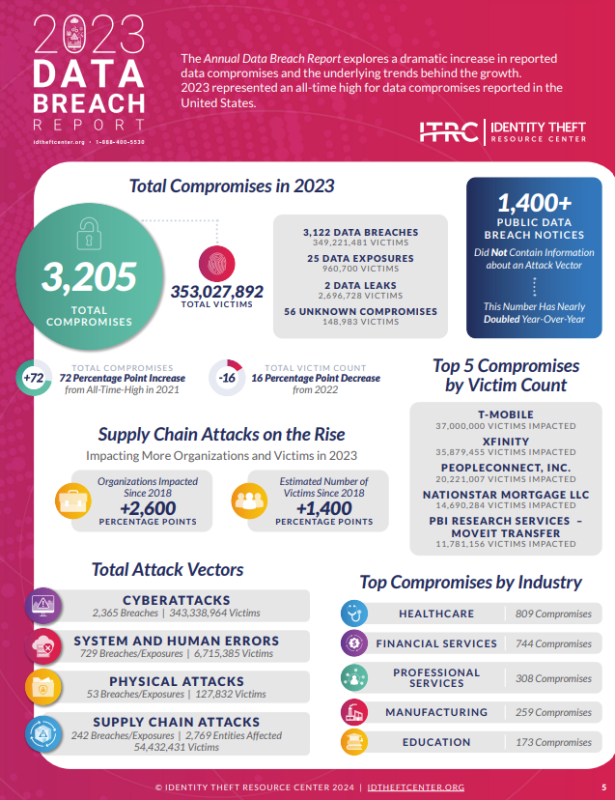

How else can we explain, as we saw in the introduction, that developers of a Bitcoin wallet are already in pretrial detention and face up to 25 years’ imprisonment for wrongdoings attributed to them in a fallacious manner, while certain financial institutions, crypto or otherwise, regularly avoid prison sentences for much more significant and serious offenses, sometimes committed consciously?

In 2012, HSBC was accused by the US government of money laundering for Mexican drug cartels and violating sanctions against countries like Iran. The laundered amounts would approach a billion dollars46. HSBC agreed to pay a record fine of $1.9 billion to US authorities.

But no prison sentences were imposed.

Again in 2012, UBS was convicted by US authorities for assisting US citizens in evading taxes by hiding undeclared assets abroad, totaling $20 billion47. UBS paid a fine of $780 million and had to provide the names of thousands of American clients.

But no prison sentences were imposed.

Better-known in France, in 2014, BNP Paribas pleaded guilty to violating US sanctions against countries such as Sudan and Iran, as well as charges of money laundering, totaling $30 billion48. The bank agreed to pay a record fine of $8.9 billion and was temporarily banned from certain dollar transactions.

But no prison sentences were imposed.

In 2019, Danske Bank was fined €150 million by Danish authorities for facilitating large-scale money laundering, involving $227 billion49 mainly from Russia.

But no prison sentences were imposed.

In 2012, Standard Chartered was accused by US authorities of money laundering for Iranian clients, bypassing US sanctions, totaling $250 billion50. The bank agreed to pay a fine of $667 million.

But no prison sentences were imposed.

$250 billion is more than the total market capitalization of Bitcoin in 2020. That’s the magnitude we’re talking about.

The largest bank in the United States, JP Morgan, has been convicted 27751 times by the courts since 2000, for a total of nearly $40 billion in fines. That’s roughly a conviction of nearly $150 million every month for 24 years, for offenses ranging from consumer protection violations to mortgage abuses, obviously including deficiencies in anti-money laundering efforts. The latter represents $2 billion out of the $40 billion in fines.

I couldn’t find a single person in traditional finance, since the 2008 crisis, who has gone to prison on charges related to anti-money laundering or terrorism financing.

In contrast, between Pertsev, the developer of Tornado Cash, who spent nine months in prison without trial and has just been sentenced to 5 years, and the developers of Samouraï Wallet, who spent some time in prison, again without trial, and one of whom was released on bail, it seems that we are right in the midst of what the Constitutional Court of Korea called “selective enforcement by authorities of the prosecutions to be initiated.”

Not So Personal Data

The third extremely dangerous point raised by these practices of collecting customer data and combating money laundering and terrorism financing is, obviously, the theft of this data.

You don’t have to go too far back in time to find examples of data breaches exploited by cybercriminals. In France, if you’ve been unemployed even once in the past 20 years, your data is no longer personal, after a hack occurred at the National Agency for unemployment, France Travail. Your name, surname, date of birth, social security number (and therefore gender, county, and city of birth), email address, postal address, and phone number: all of this is now in the wild, in the hands of cybercriminals, who have already started using it for their deeds.

Of course, what happened to France Travail also happens in the world of finance.

Among the biggest data breaches in recent years, we can mention Equifax in 2017, an American credit rating agency, affecting the personal data of over 150 million people 52 53, or JP Morgan in 2014, with 76 million households and 7 million businesses54, or Capital One in 2019, with over 100 million affected customers, among the largest in recent years. Europe is not spared either: HSBC has experienced multiple data breaches over the past ten years55 56, but fintech companies like Revolut57 are also not immune.

In short, once your personal data is collected, the question is no longer “if” but “when” it will be accessible to hackers.

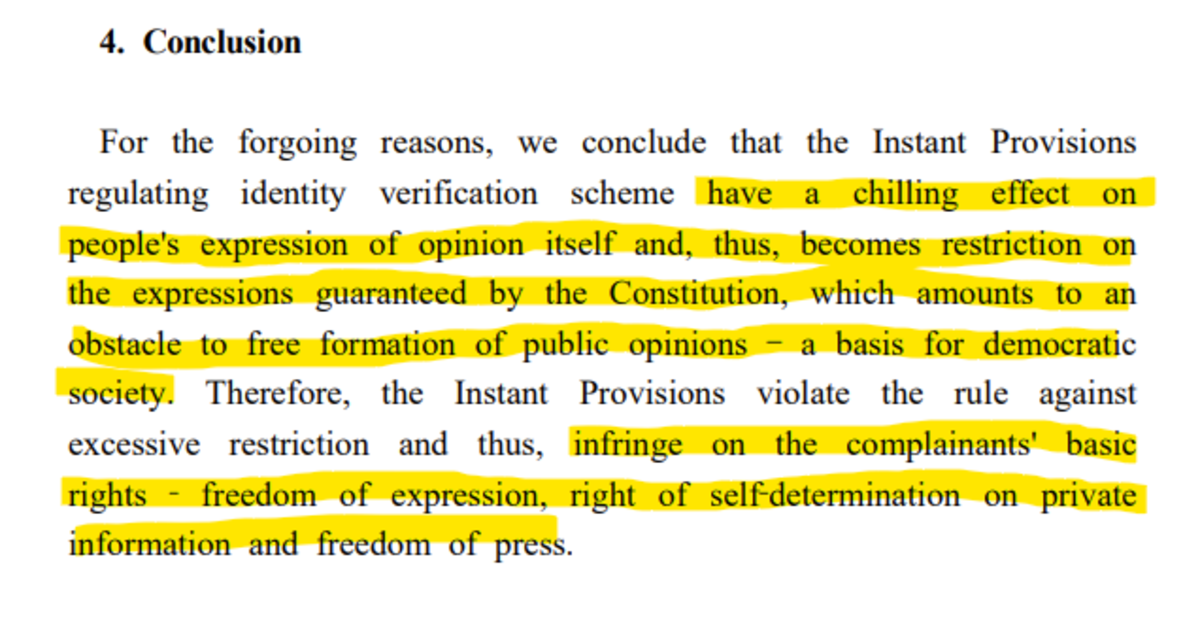

According to the Identity Theft Resource Center (ITRC), an American NGO dedicated since 1999 to evaluating identity theft crimes in the United States, there were over 3,200 data breaches or hacking events in 2023 in the United States, affecting over 350 million victims. That’s more than the entire population of the country. The financial industry emerges as the main victim, just behind the medical industry and its valuable health data58.

According to the US Federal Trade Commission, credit card frauds between 2019 and 2023 increased by over 50%, from about 280,000 consumer complaints to over 425,00059. Among these frauds, about 90% resulted from identity theft that allowed the opening of a new account in the name of a person who had their personal information stolen, and only 10% resulted from fraud on an existing card.

According to Transunion, a company that collects, monitors, and protects banking data, the use of personal data to forge new false identities reached new records in 2023, resulting in a loss of $3 billion in the United States60.

Especially with the development of AI, which reaches frightening levels of sophistication in terms of identity theft (voice, video, etc.), it becomes necessary for this “free-for-all” personal data to stop as soon as possible. Protecting personal data is therefore also a moral duty towards others because protecting oneself is protecting others from scams and breaches of trust.

It is therefore a matter of physical and digital safety for everyone. This is particularly the fight that has been launched in Switzerland, where the canton of Geneva has already voted 94% in favor of amending the constitution in favor of creating a right to digital integrity61.

Conclusion: An excessive, Unjustified, and Counterproductive Lockdown that Tramples Fundamental Rights

The practices and instruments of financial regulation impose extreme limitations on the exercise of several fundamental rights and freedoms. In particular, they disproportionately reduce both monetary confidentiality and the freedom to dispose of one’s own funds, while leading to the prohibition, legal or practical, of technologies and tools regardless of their use, as well as differences in treatment, for a given behavior, depending on the actor involved. By extension, this deals a fatal blow to innovation in Europe.

However, these practices and regulations have not been justified, as their effectiveness in combating money laundering and terrorism financing has not been “convincingly demonstrated”62, which is an obligation for the State in any endeavor to limit freedoms.

Conversely, they pose greater risks, for individuals and society, than those they claim to combat, particularly in terms of the protection of personal data (the fact that individuals cannot escape a major risk concerning very sensitive data also constitutes an infringement of their dignity).

Finally, their cost to the economy – and thus the freedom of enterprise – alone surpasses the proceeds of the crimes they claim to target.

In these circumstances, the infringements on the aforementioned fundamental rights are arbitrary and unacceptable in a democratic society.

More specifically, firstly, the rights to dignity, self-determination, and resistance to oppression are trampled upon. A substantial part of the right to property is nothing more than a chimera in a Europe where individuals must seek permission before spending their own money, without being certain that it will not be blocked the next day for a reason that has no legal basis and against which there is no effective remedy. The freedom of trade and industry is curtailed by the inability to develop innovative tools.

The right to privacy, more generally, is also violated to the point of annihilating its very essence: when anonymous cryptos are banned, and transfers without KYC are blocked, before any suspicion of wrongdoing and therefore regardless of their illicit use or not, it is privacy itself that is targeted, even though it constitutes the normal exercise of privacy.

Yet, the right to privacy protection is a pillar of democracy: described as “fundamentally fundamental” in that it “preconditions the enjoyment of most other rights and freedoms”63, it is intended “to ensure the development, without external interference, of the personality of each individual in relations with others,” to use the terms of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR)64. This capacity for personal development, associated with the freedom to make choices in complete confidentiality, guarantees the “democratic functioning of society”65.

To impose limitations on any of these fundamental freedoms, a clear and precise legal basis, motivated by a demonstrated necessity, strictly proportionate, with guarantees to attest to it is rightly expected.

But none of this is complied with as it stands. It is the advent of a presumption of guilt that paves the way for the selective application of disproportionate laws, by governments, but also by financial actors. The hypertrophy of the banking sector is indeed largely the child of these regulations, imposing staggering costs and consequently concentration, protected by giant entry barriers, leading de facto to recurring abuses of dominant position.

Preventive control of everyone, all the time, before the slightest suspicion of committing an offense, becomes the norm. Even though the European Court of Human Rights and the Court of Justice of the European Union prohibit it. For companies subject to these regulations, the absence of control becomes an offense, in violation of primary law.

This situation should frighten any citizen desiring to live in a liberal democracy.

Thanks to Estelle De Marco, Doctor of Private Law and Criminal Sciences, expert with the Council of Europe specializing in the protection of fundamental rights, for her contribution on legal developments.

[36] World Bank Group, What Does Digital Money Mean for Emerging Market and Developing Economies?, 2022, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099736004212241389/pdf/P17300602cf6160aa094db0c3b4f5b072fc.pdf

[37] Anti-Money Laundering Regulation EU, 2024, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2024-0365_EN.pdf

[38] Cour EDH, Podchasov v. Russia, https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/?i=001-230854.

[39] Does crime still pay? Criminal Asset Recovery in the EU, Survey of Statistical Information 2010–2014, 2016, https://www.europol.europa.eu/cms/sites/default/files/documents/criminal_asset_recovery_in_the_eu_web_version.pdf

[40] Voir les références dans le papier de Ronald Pol.

[41] Paul Vieira, Canada’s Use of Emergency Powers to End Trucker Protests Was Unconstitutional, Judge Rules, 2024, https://www.wsj.com/world/americas/canadas-use-of-emergency-powers-to-end-trucker-protests-was-unconstitutional-judge-rules-6a537434

[42] https://twitter.com/Nigel_Farage/status/1674357026921623552

[43] Ben Quinn, Jim Waterson, BBC writes to Farage to apologise over Coutts bank account report, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2023/jul/24/bbc-writes-to-farage-to-apologise-over-coutts-bank-account-report

[44] https://twitter.com/DavidDavisMP/status/1681656257600532481

[45] Human Rights Foundation, The Financial Freedom Report #17, 2024, https://mailchi.mp/hrf.org/hrfs-weekly-financial-freedom-report-290691

[46] https://twitter.com/incindia/status/1770707793730838967?mc_eid=332f07f5f9

[47] Main Modi opponent Kejriwal challenges arrest ahead of India election, 2024, https://www.france24.com/en/asia-pacific/20240322-modi-s-main-opponent-kejriwal-held-in-graft-probe-ahead-of-indian-elections

[48] https://english.ccourt.go.kr/ “Identity Verification System on Internet”, 23 Août 2012

[49] Marc L. Ross, HSBC’s Money Laundering Scandal, 2023, https://www.investopedia.com/stock-analysis/2013/investing-news-for-jan-29-hsbcs-money-laundering-scandal-hbc-scbff-ing-cs-rbs0129.aspx#:~:text=HSBC%20Bank%20USA%20laundered%20%24881,to%20result%20from%20systematic%20failures.

[50] Trial Begins for Ex-UBS Banker Accused of Hiding $20 Billion in US Assets, 2014, https://www.occrp.org/en/daily/2675-trial-begins-for-ex-ubs-banker-accused-of-hiding-20-billion-in-us-assets

[51] BNP Paribas accepte de payer une amende record aux Etats-Unis, 2014, https://www.leparisien.fr/economie/bnp-paribas-le-montant-de-l-amende-fixe-ce-lundi-soir-30-06-2014-3964657.php

[52] Teis Jensen, Danske Bank’s 200 billion euro money laundering scandal, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKCN1NO10D/

[53] Dominic Rushe, Jill Treanor, Standard Chartered bank accused of scheming with Iran to hide transactions, 2012, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2012/aug/06/standard-chartered-iran-transactions#:~:text=Standard%20Chartered%20bank%20ran%20a,of%20the%20UK%2Dbased%20bank.

[54] Violation Tracker, Parent Company JP Morgan Chase https://violationtracker.goodjobsfirst.org/?parent=jpmorgan-chase

[55] Todd Haselton, Credit reporting firm Equifax says data breach could potentially affect 143 million US consumers, 2017, https://www.cnbc.com/2017/09/07/credit-reporting-firm-equifax-says-cybersecurity-incident-could-potentially-affect-143-million-us-consumers.html

[56] FCA, Final Notice to Equifax Unlimited, 2023, https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/final-notices/equifax-limited-2023.pdf

[57] Tara Siegel Bernard, Ways to Protect Yourself After the JPMorgan Hacking, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/04/your-money/jpmorgan-chase-hack-ways-to-protect-yourself.html

[58] Scott Ferguson, HSBC Data Breach Shows Failure to Protect Passwords & Access Controls, 2018, https://www.darkreading.com/cyber-risk/hsbc-data-breach-shows-failure-to-protect-passwords-access-controls

[59] Elise Viebeck, HSBC Finance alerts customers to data breach, 2015, https://thehill.com/policy/cybersecurity/239408-hsbc-finance-alerts-customers-to-data-breach/

[60] Carly Page, Revolut confirms cyberattack exposed personal data of tens of thousands of users, 2022 https://techcrunch.com/2022/09/20/revolut-cyb erattack-thousands-exposed/

[61] 2023 Data Breach Report, Identity Theft Resource Center, 2024, https://www.idtheftcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/ITRC_2023-Annual-Data-Breach-Report.pdf

[62] Federal Trade Commission, Identity Theft Reports, 25 avril 2024 (données du 31 mars 2024), https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/federal.trade.commission/viz/IdentityTheftReports/TheftTypesOverTime

[63] TransUnion, TransUnion Analysis Finds Synthetic Identity Fraud Growing to Record Levels, 24 août 2023, https://newsroom.transunion.com/transunion-analysis-finds-synthetic-identity-fraud-growing-to-record-levels/

[64] Yannick Chavanne, Genève fait figure de pionnier en introduisant l’intégrité numérique dans sa Constitution, 2023, https://www.ictjournal.ch/news/2023-06-19/geneve-fait-figure-de-pionnier-en-introduisant-lintegrite-numerique-dans-sa

[65] Cour EDH, ch., 25 février 1993, Crémieux c. France, req. n°11471/85, § 38, https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/fre?i=001-62362.

[66] Antoinette Rouvroy et Yves Poullet, ‘The right to Informational Self-Determination and the Value of Self-Development: Reassessing the Importance of Privacy for Democracy’, in Serge Gutwirth et al., Reinventing Data Protection?, janvier 2009, p. 45–76, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/225248944_The_Right_to_Informational_Self-Determination_and_the_Value_of_Self-Development_Reassessing_the_Importance_of_Privacy_for_Democracy , p. 16. See also Fabrice Rochelandet, ‘II. Quelles justifications à la vie privée ?’, in Économie des données personnelles et de la vie privée (2010), p. 21–37, https://www.cairn.info/Economie-des-donnees-personnelles-et-de-la-vie-pri–9782707157652-page-21.htm?contenu=resume. Voir aussi Antoine Buyse, ‘The Role of Human Dignity in ECHR Case-Law’, 21 octobre 2016, https://www.echrblog.com/2016/10/the-role-of-human-dignity-in-echr-case.html .

[67] CEDH, Botta v. Italie, 1998, §32, https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-62701.

[68] Antoinette Rouvroy et Yves Poullet, précités, p. 13.

This is a guest post by Alexandre Stachtchenko. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.

Source link

Opinion

Accelerating Bitcoin Programmability With The Solana Virtual Machine

Published

16 hours agoon

July 2, 2024By

admin

Bitcoin & Beyond is an educational series by the team at The Rollup focused on a new and emerging class of builders in the Bitcoin ecosystem. Through spaces, panels, and interactive presentations, the objective is to provide deep technical insights into innovative scaling projects.

In an interview with Chase from Molecule, we dive into the growing appetite for next-generation virtual machines (VMs) aimed at enhancing Bitcoin’s programmability and scalability. Molecule is one company at the forefront of this experiment. Their attempt to implement Solana’s Virtual Machine (SVM) with Bitcoin is a strong signal that builders are also considering alternatives to the popular Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM).

High-Performance VMs for Bitcoin

Chase emphasized that Molecule’s goal is to leverage the most performant execution environment to benefit Bitcoin users. He believes the Solana Virtual Machine (SVM) offers unparalleled throughput and cost efficiency. “SVM provides the highest throughput with a super battle-tested execution environment,” Chase noted, highlighting the VM’s ability to achieve 1000 transactions per second at a fraction of a penny per transaction.

The SVM’s architecture, designed for parallel transaction processing, significantly enhances scalability and efficiency. At a very basic level, it enables the concurrent execution of multiple smart contracts, setting SVM apart from other VMs that rely on sequential processing models, like the EVM. This results in higher throughput and lower latency, crucial for applications requiring high performance and minimal transaction costs

A Thriving Developer Ecosystem

A key reason for Molecule’s decision to adopt the Solana Virtual Machine (SVM) lies in its thriving developer ecosystem and the wide adoption of Rust as a programming language. Solana boasts over 3,300 active developers as of late 2023, according to Electric Capital. This robust community is supported by extensive tooling and educational resources which have significantly improved developer retention.

Chase also brought up Rust, Solana’s development language, as playing a crucial role in the SVM’s success. With over 3 million Rust developers globally, the transition to using SVM is seamless for many, given their familiarity with the language. This extensive developer base and the language’s strong integration within Web3 ecosystems ensure that SVM is not only technically superior but also advantageous for broader adoption and innovation.

By focusing on a VM that aligns well with developer preferences and offers a robust, scalable environment, Molecule ensures they are building on a foundation that encourages rapid development and deployment of new applications on Bitcoin.

Monolithic vs. Modular Vision

Another emphasis was on the inherent limitations of Bitcoin’s Layer 1, which necessitate a modular approach to enhance programmability and scalability. Traditional monolithic blockchains integrate all core functions—execution, data availability, consensus, and settlement—into a single layer. While this design enhances security and decentralization, it also creates significant bottlenecks that limit transaction throughput and flexibility. Bitcoin’s Layer 1 can process only a limited number of transactions per second, restricting its ability to support complex smart contracts and higher transaction volumes

To address these constraints, Molecule adopts a modular approach, decoupling these functions into distinct layers. This architecture allows for the specialization and optimization of each layer, significantly improving scalability and efficiency. By leveraging modular stacks, Molecule aims to integrate Solana’s execution layer (SVM) with ZK (zero-knowledge) verification for transactions on Bitcoin.

Molecule’s innovative SVM rollup stack focuses on enabling ZK verification of transactions through a ZKVM (Zero-Knowledge Virtual Machine) and posting ZK snarks (Succinct Non-Interactive Arguments of Knowledge) to Bitcoin using a challenge-reward mechanism. This method ensures secure and efficient transaction finalization on Bitcoin.

Molecule is considering different options for this challenge mechanism, potentially using BitVM or a variant based on a future OP_CAT soft fork. BitVM utilizes a challenge-prover system where any verifier can contest transactions during a predefined challenge period, ensuring the integrity and accuracy of asset transfers. Chase explained, “you can verify any asset transfers from molecule back to Bitcoin. There’s a challenge period where you can, any verifier can come in and say that, hey, there’s some issues, then they can go through this challenge mechanism.” This approach blends off-chain computation with on-chain verification, providing a robust and cost-effective solution for maintaining transaction finality and security.

A new Bitcoin L2 narrative

When asked about the Bitcoin community’s stance on Layer 2 (L2) solutions, Chase observed a notable shift in attitude towards embracing programmability. Traditionally, many Bitcoin purists have been wary of L2 solutions, fearing they might compromise the network’s security and decentralization. However, recent advancements and the increasing demand for more scalable applications have started to change this perspective.

“I think the Bitcoin community definitely demands programmability for Bitcoin. SVM is the best solution to that in terms of throughput and cost,” Chase stated, underscoring the community’s evolving openness to L2 innovations.

Molecule’s innovative approach and commitment to integrating high-performance virtual machines (VMs) with Bitcoin mark a transformative step towards enhancing Bitcoin’s utility and scalability.

This is a guest post by The Rollup. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.

Source link

democracy

How Financial Surveillance Threatens Our Democracies: Part 1

Published

2 days agoon

July 1, 2024By

admin

When they descended into coal mines, miners would take a caged canary with them. The toxic gasses, notably carbon monoxide, that accumulate in these places and pose a deadly risk to miners, would kill the canaries before the miners. This information made them aware of the danger, enabling them to evacuate before it was too late.

On May 14, 2024, Alexey Pertsev, a software developer who built an open-source tool to preserve online privacy, was found guilty of money laundering and sentenced to more than 5 years in prison by a Dutch court.

In the court’s decision, the following can be read: “The tool developed by the suspect and his co-authors combines maximum anonymity and optimal concealment techniques with a serious lack of identification functionalities. Therefore, the tool cannot be characterized as a legitimate tool that has been inadvertently used by criminals. By its nature and operation, the tool is specifically intended for criminals.”

Seeking to preserve one’s privacy is thus at worst proof of criminality, at best complicity in a crime. A threshold has been crossed.

Unfortunately, it is likely that this case will generate little empathy and interest, as the person involved worked in the crypto industry, and the tool developed, Tornado Cash, was intended to preserve transaction confidentiality.

However, it would be a grave mistake to consider this an isolated incident limited to a fledgling industry for which the public has little affection.

This is our canary in the coal mine.

It has stopped singing and is dying. If we do not react, all the miners will perish. Cryptos are an early and glaring revealer of an insidious phenomenon that has been eroding our liberal democracies for about thirty years and is reaching a point of no return.

Despite the lack of evidence of their effectiveness, financial surveillance measures continue to be regularly reinforced, defying all democratic rules and requirements: the primacy of secrecy, freedom as a norm, the principle of proportionality of rights limitations, technological neutrality, presumption of innocence… Preemptive control prior to any offense becomes the norm, the enforcement of law becomes selective and arbitrary, bank account closures take on the appearance of censorship and financial suffocation, and property rights are reduced to a mere shadow.

The fight against money laundering and terrorist financing has degenerated into collective hysteria worthy of authoritarian or even totalitarian regimes, to the point of criminalizing a fundamental and constitutional right: privacy. The famous American computer engineer Phil Zimmermann warned us in 1991: “if privacy is outlawed, only outlaws will have privacy.”

Far from being a “crypto” issue, this shift away from liberal democracy concerns everyone. There are numerous examples in regimes known for their democracy, spanning from India to the United Kingdom, and from Canada to France.

Note: If the crypto part does not interest you, you can proceed directly to part II.

I. Lessons from the Canary

1. The United States Involves Itself

Less than a year ago, the arrest of the Tornado Cash developers had already legitimately caused quite a stir. But the scope of the case, limited to the crypto world, perceived as a den of terrorists and money launderers, had quickly confined the indignation to a small group of insiders.

In April 2024, American and European public authorities, emboldened by this success, continued to move forward in a worrying direction.1

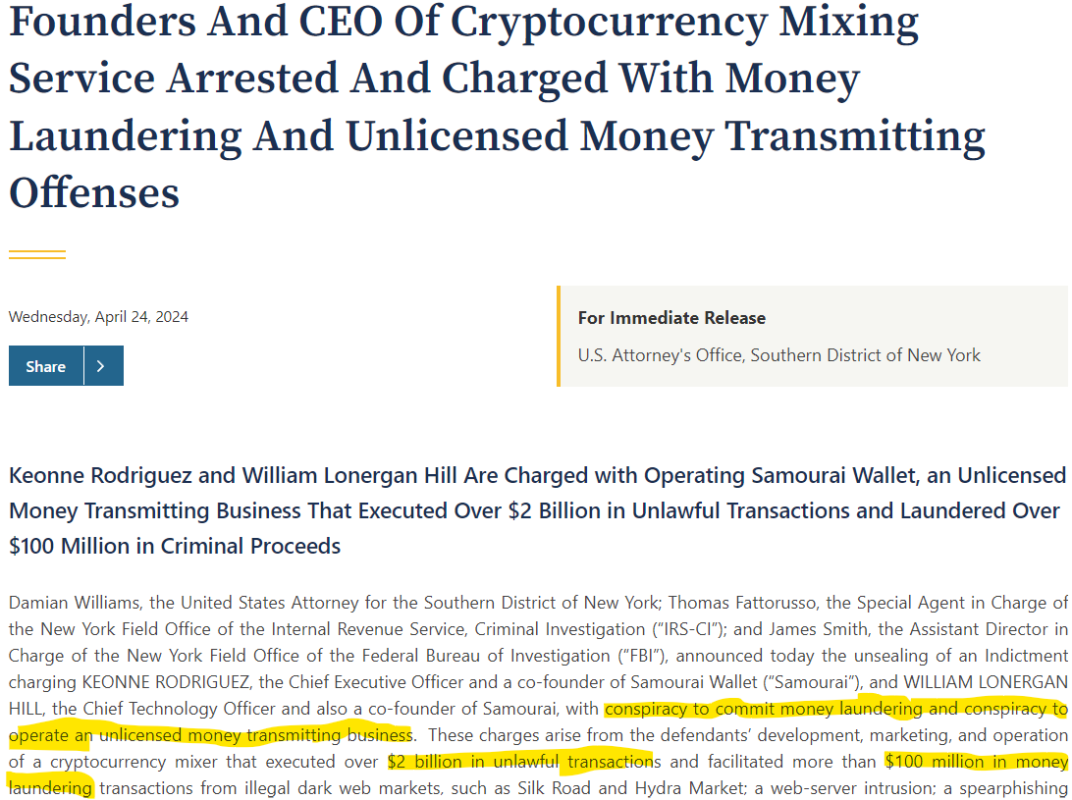

Several events occurred almost simultaneously. The arrest of the developers of the Bitcoin wallet developers of Samourai Wallet, by the FBI in cooperation with the IRS (the American tax authority), with the guilty cooperation of European authorities, kicked things off. Their crime would be to have “conspired to launder money” and to have “operated an unlicensed money transfer business”.2 They face 20 years’ imprisonment for the first charge and 5 years for the second. By comparison, the maximum irreducible life sentence in France is 30 years.

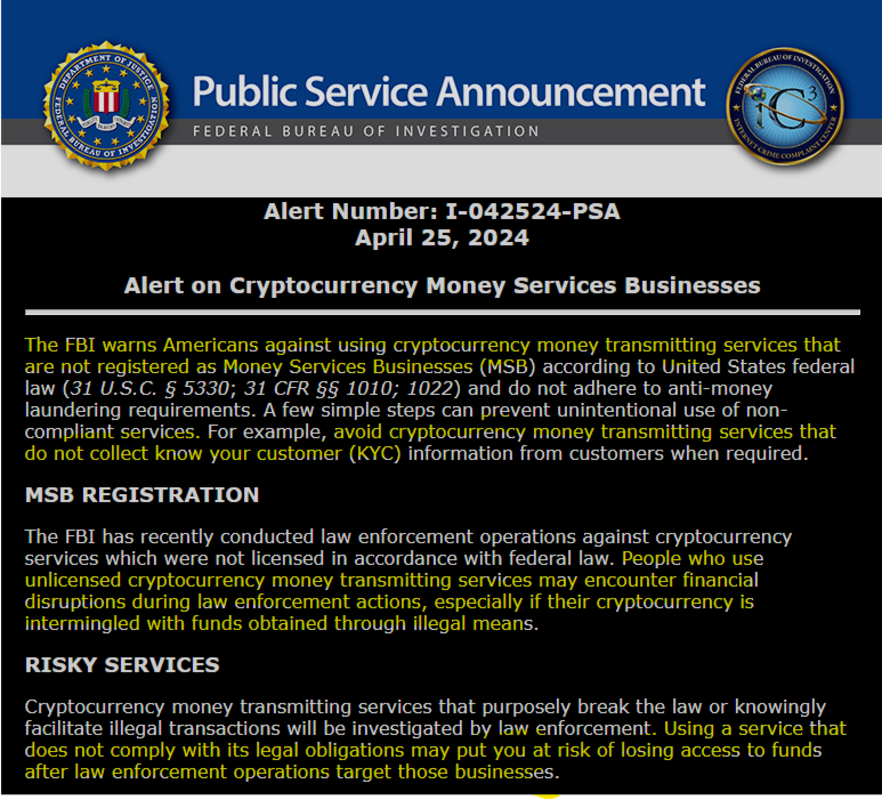

Following this was an FBI notice3 urging all Americans not to use “money transmitting businesses” that do not collect their identity and are not registered. And the Federal Bureau continued by threatening to freeze all funds that had been mixed with funds obtained through illegal means.

To better understand the absurdity of such an announcement by the FBI, let us transpose the reasoning into the physical world, and highlight two major issues.

The first concerns the accusation of operating an unlicensed money transfer business.

Samourai Wallet is a company that provides Bitcoin wallets with enhanced transaction privacy. It does not operate transactions on behalf of its clients; it provides the wallet software. In the physical world, their equivalent would be a leather craftsman who crafts leather wallets enabling their users to store cash. He facilitates cash management but has no say in how the wallet owners spend their cash.

Here, the U.S. federal services conflate and lump together a large bank that operates transactions on behalf of its clients and a leather craftsman, holding the latter responsible for how his clients use their cash.

How far can we go with this line of reasoning? To ATMs? To the people at the Central Bank who print these bills? To the lumberjacks who produce the wood used for the paper of the bills?

Similarly, should we hold a carpenter responsible for what his clients decide to put in the furniture they make? Or an architect if the house they build ends up being used for drug trafficking?

It quickly becomes apparent that this conflation is completely absurd. A wallet creator is not responsible for what the wallet owner decides to do with the money stored in it. Being part of the cash or cash storage value chain should in no way imply responsibility for its final use, as there is no limit to this reasoning.

This question was actually raised 20 years ago regarding peer-to-peer exchanges, which allow multiple people to exchange information directly in a decentralized manner. This communication protocol and the software that enable it are sometimes used to commit offenses, particularly against intellectual property rights. However, despite attempts to criminalize the tool itself4, European5 and American6 courts have ruled in favor of technological neutrality, stating that the software in question allows both legal and illegal exchanges and that their providers are not responsible for the use made by third parties. The case law then focused on the responsibility of each individual involved in a potentially illegal activity, acquitting some individuals due to lack of evidence of their criminal intent7. These judicial solutions are obviously in line with the normal exercise of fundamental rights.

The second issue lies in the threat of fund blocking.

Freezing any money mixed with funds obtained through illegal means would be equivalent to arresting anyone whose bills, whether in their leather wallet or pocket, have passed through the wrong hands.

In 2009, a university study covered by CNN showed that 90% of American dollar bills carry traces of cocaine, and up to 100% in some major cities8. This helps us better understand the absurdity of the FBI’s threat: almost all the cash in the world has already passed through the wrong hands. Should all cash holders be imprisoned? Of course not.

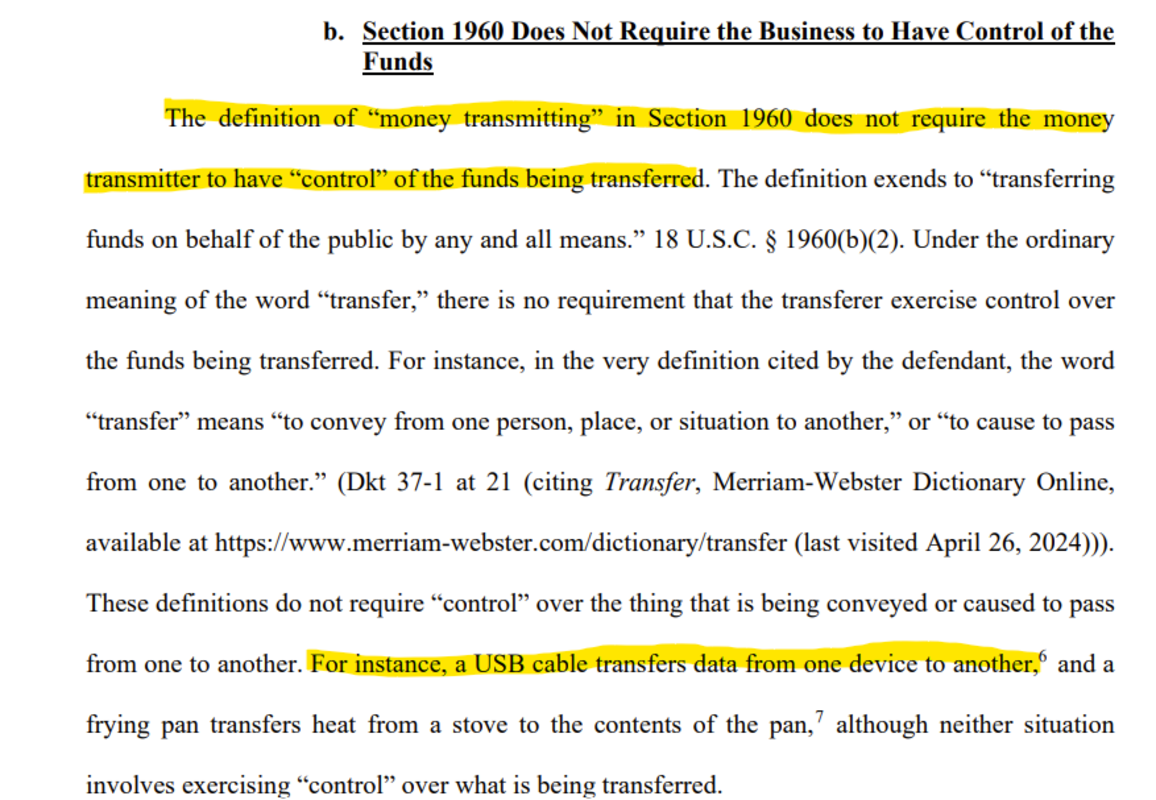

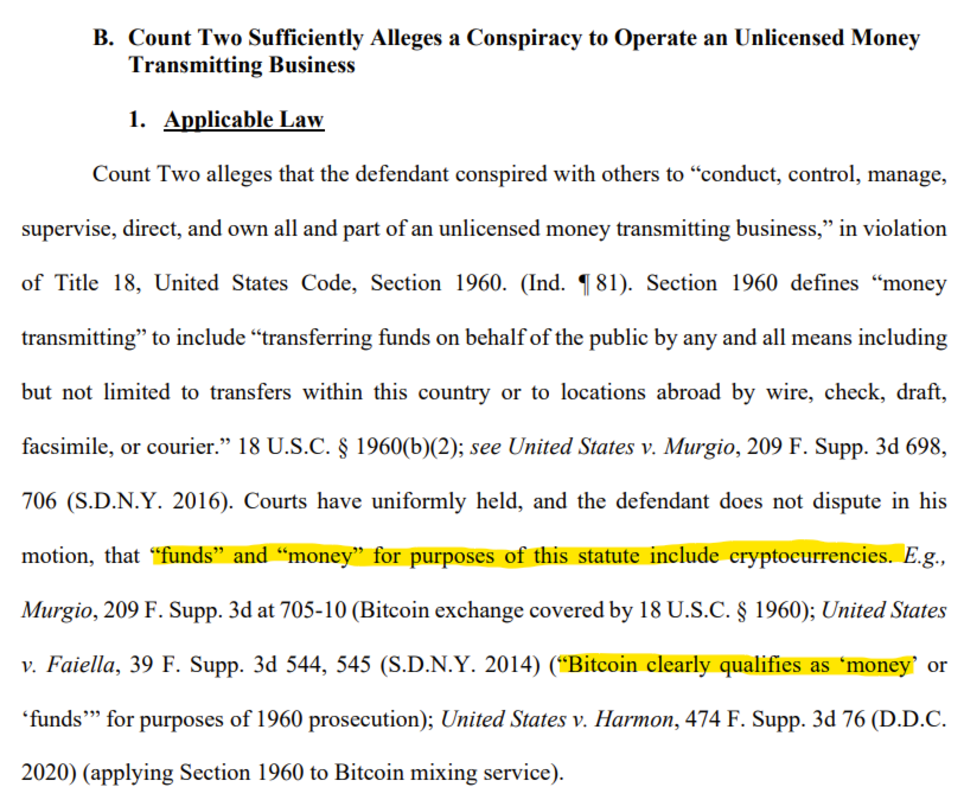

Following these absurd coercive actions, on 26 April 2024, the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York published the government’s rationale against Roman Storm9, the lead developer of the privacy software Tornado Cash. The author insists, considering Tornado Cash as a “money transmitting business.”

According to this argument, “the definition of “money transmitting” in Section 1960 does not require the money transmitter to have ‘control’ of the funds being transferred. […] For instance, a USB cable transfers data from one device to another […].”

A very broad definition of a “money transmitting business” that would even include USB cables, according to their own admission. At this rate, the question will soon become “who is not a money transmitter?”

Here, the DOJ (Department of Justice) is so ambitious that it goes against the guidelines provided by FinCen (Financial Crime Enforcement Network, a bureau of the U.S. Treasury Department). In other words, the U.S. government does not agree with itself, which indicates a certain uneasiness.

In 2013, FinCen explained that software developers were not “money transmitters” (“The production and distribution of software, in and of itself, does not constitute acceptance and transmission of value, even if the purpose of the software is to facilitate the sale of virtual currency.”10).

In 2019, following an inquiry regarding certain programmable features on Bitcoin (Time-locked and multi-signature), FinCen reiterated that the partial control that could be exercised by wallet developers was not sufficient to qualify them as “money transmitters” (“the person participating in the transaction to provide additional validation at the request of the owner does not have totally independent control over the value.”11).

2. Europe at the Forefront of an Illiberal Shift

Beyond the opportunistic qualifications of various parties and to return more simply to the way the law should be applied in a liberal democracy, let’s recall that cryptocurrency transfers are transfers of electronic communications according to the definition provided by European Union law12.

Moreover, cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin or Ethereum allow for the exchange of communications that can be qualified as correspondences (the possibilities of exchange are not limited to monetary units). Electronic communications are protected by the right to privacy and personal data protection, and a limitation such as lifting confidentiality or blocking can only be justified if it is necessary for the effective pursuit of a defined objective, in a strictly proportionate manner, particularly in the case of a proven offense and personally committed by the individual whose communication is limited.

The Court of Justice of the European Union has also ruled in this sense, considering that the systematic analysis of communications, even when possible, infringes on the fundamental right to the protection of users’ personal data, in violation of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. The Court specifies that an injunction to block communications that does not distinguish “between illegal and legal content […] could result in the blocking of communications with legal content” and thus infringe on the freedom of expression and communication13. Regarding cryptocurrency transfers, we can also invoke an infringement on the right to property.

It is therefore inconceivable, in a liberal democracy, to ask a private actor to block transactions or other types of communications without being certain of their illegality.

We can note another convenient schizophrenia on the part of the American authorities, which Lyn Alden aptly summarizes by referring to “Schrödinger’s Currency”14: Bitcoin is considered as a currency only when it allows for the prosecution of individuals. The rest of the time, it is a speculative tool to which this qualification is denied. Indeed, to apply the definition of “money transmitter,” it is necessary to consider that what is being transmitted (bitcoins) is indeed money. To the point that the government argues that “Bitcoin clearly qualifies as money” in order to prosecute Roman Storm.

Europe regularly engages in this distortion as well, as I had already shown in the justification invoked to include “crypto-assets” in the TFR regulation. Cryptos have indeed appeared in a text that previously targeted exclusively “banknotes and coins, scriptural money, and electronic money.” But to say that Bitcoin is a currency…

Moreover, in Europe, coincidentally, a new regulation was voted on April 25 imposing new financial constraints, still with the laudable objective of combating money laundering15.

Among the constraints, we can particularly note a €10,000 cash payment limit across Europe, but also the requirement for digital asset service providers (DASPs) to collect even more information about their clients, including for transactions under €1,000, and for personal wallets, known as “self-custodial,” “self-hosted,” or “un-hosted,” i.e., not managed by a financial intermediary on behalf of third parties. The leather wallets of the digital world.

A small digression into Newspeak here: by imposing the terminology “self-hosted” or “un-hosted,” regulators and legislators are trying to enforce the view that third-party custody is the norm, and self-custody is the exception. This is obviously a dangerous and insidious view, suggesting that wanting to keep one’s own money is suspicious, even though it is part of the normal exercise of freedoms. There are no “un-hosted” or “self-hosted” wallets. There are just wallets, period. And there are third parties who hold wallets on behalf of others.

Returning to the text, let’s casually note that it is particularly precise and imposes know-your-customer (KYC) requirements for transactions under €1,000 only on DASPs, exempting banks and other financial institutions, which handle far larger volumes than DASPs. The proportionality of this amount and this discrimination is not justified.

In addition, there is a ban on supporting enhanced privacy cryptocurrencies. Let us recall here that historical commodity monies (gold, silver, copper, bones, etc.) are anonymous, as is still cash today. The ban is therefore inequitable and strikes under the pretext of its electronic nature. It is again unjustified, although it unacceptably hinders the normal exercise of a freedom since we are talking about its outright extinction (such a disproportion is not admitted by the European Court of Human Rights16).

As previously mentioned, all these actions are extremely problematic in several respects.

First, because these constraints are based on no rational reasoning or relevant justification and are simply the result of paranoia related to cryptos, coupled with a KYC model (Know Your Customer, the customer identification processes imposed on financial institutions) that has been elevated to a religion despite the lack of convincing results over several decades. Second, because they disregard the requirements for the protection of fundamental freedoms on which the European Union was built and to which it is subject. Third, because they are counterproductive, meaning they create new threats, the consequences of which are increasingly severe.

3. An Unfounded Paranoia

Nearly all texts dealing with the “necessary” regulation of “crypto-assets” have abandoned scientific and legal rigor to the point of never proving the initial assertion from which their reasoning starts: “cryptos are a good means to facilitate money laundering.”

To appreciate this, one only needs to analyze all the texts on the subject issued in recent years. This is an exercise I have already done for the TFR text17. Indeed, in the “proportionality” paragraph of the proposed amendment to the regulation, there is a small phrase indicating that, according to the opinion of EU surveillance authorities, “specific” risk-increasing factors have been identified concerning cryptos.

Why is proportionality an extremely important principle in a state governed by the rule of law?

Because the adequacy of a legislative standard or instrument to the pursued objective, i.e., the balance between the infringement on a right and the general interest, is absolutely crucial to avoid authoritarian and liberty-infringing drifts. One cannot hide behind an objective, however commendable, to impose disproportionate restrictions on rights.

For example, one might think that by installing a policeman in everyone’s home, crime would be reduced. The objective may be considered laudable, but the individual rights that would be compromised in the process represent an unacceptable reduction in freedoms. Thus, society decides to tolerate potentially higher crime rates (subject to the risks to freedoms generated by surveillance itself) in order to preserve the rule of law and fundamental freedoms, without which democracy cannot exist.

Conversely, the prohibition of alcohol while driving is a restriction that can be considered proportionate: alcohol consumption is not prohibited, but it is prohibited in situations where its consumption is systematically dangerous for oneself and others. The impacts of such legislation can be monitored by observing the number of accidents, for example. A right has been restricted, certainly, but the general interest prevails since the effectiveness of the measure in relation to an important objective (the preservation of life) can be demonstrated, and the infringement on rights is minimized by limiting the restrictions as much as possible.

In a liberal democracy, freedom is the norm and constraints the exception. It is up to the state, when it wishes to restrict a freedom, to demonstrate that it does not go further than necessary to achieve its objective and that this objective is effectively achieved18. Furthermore, the state is obliged to adopt norms to ensure that all persons and institutions, both public and private, respect this rule19.

In the case at hand (money laundering and terrorist financing), and despite the assertion that “supervisory authorities have identified specific risk factors,” when one plays the detective wishing to trace back to the source, one realizes that the opinion in question, dating from 2019, itself admits that the so-called “competent authorities” do not have the “knowledge and understanding of these products and assets, which prevents them from carrying out a proper impact assessment.”20

It also deflects by referring to another opinion (sic) from the European Banking Authority, which dates back to… 2014. In this “original” opinion, we find a rather laconic analysis: “the phenomenon of Virtual Currencies being assessed has not existed for a sufficient amount of time for there to be quantitative evidence available of the existing risks, nor is this of the quality required for a robust ranking.”21

In other words, the TFR regulation, imposing monitoring of all crypto transfers from one provider to another, was built on the basis of two reports. One report stated that there was no evidence to qualify or quantify the risks, while the other admitted that competent authorities lacked the knowledge and understanding to conduct an analysis.

Therefore, concluding the paragraph on the “proportionality” of the TFR regulation by stating that “In accordance with the principle of Proportionality as set out in Article 5 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU), this regulation does not exceed what is necessary to achieve its objectives” is questionable at best. Since the risks are not assessed, it seems difficult to characterize the restriction of rights as “proportionate.”

In his fight against FINMA, Alexis Roussel made the same observation for Switzerland. The Swiss National Risk Assessment (NRA) of 201822 regarding money laundering risks in crypto indicates, from its very first sentence, that no cases of terrorism financing related to crypto have been identified, and only rare cases of money laundering. However, the subsequent statement recommends classifying these assets as “high-risk” by their very nature. Specifically, this means that a crypto transaction, even of €10, carries the same level of risk as a €100,000 transfer to an account in Russia. This equivalence is established without democratic processes in Switzerland and without any evidence.

The 2024 NRA23 does not seem to have made much progress and still admits to lacking data to assess risks.

We can clearly see a pattern emerge: anti-money laundering regulations and increasingly stringent data collection requirements are imposed without legitimate basis or factual data to justify their implementation.

A more comprehensive overview has been provided by L0la L33tz in Bitcoin Magazine24, allowing us to supplement this inventory of breaches of the most basic rigor in Europe, as well as by sister institutions of Bretton-Woods, the IMF, and the World Bank, which are true compasses for global decision-makers.

For example, in 2023, the annual report for 2021 from the European Union’s FSRB (the European branch of the Financial Action Task Force, FATF)25, an intergovernmental group established in 1989 to combat money laundering and terrorism financing, was released.

The report begins with the following quote: “It is well known that money launderers have abused cryptocurrencies, initially to transfer and conceal profits generated from drug trafficking. Nowadays, their methods are becoming increasingly sophisticated and on a larger scale.”

Unfortunately, starting an argument with “it is well known” reads the same as an essay that begins with “Throughout history, mankind”: it does not exude the rigor of thorough research.

The report itself admits that a study will be dedicated in 2022 to analyzing money laundering trends in cryptocurrencies, suggesting that it did not exist at the time of writing the report, asserting as an obvious truth what had never been studied.

This report dedicated to the study of money laundering trends in cryptocurrencies has indeed been published26, but it focuses not on the phenomenon itself but rather on the analysis of the implementation of regulations. Regulations that, it is worth noting, are based on unproven money laundering.

Regarding the study of facts and the field, the report interestingly notes that the risk assessment “lacks depth.” It also observes that the majority of regulators lack the tools and expertise necessary to effectively analyze and investigate cases of money laundering and terrorism financing related to “virtual assets.”

The study also takes the same shortcut as the aforementioned Swiss analysis: finding very few cases of money laundering involving virtual assets, it prefers to conclude that it is because more regulation is needed, rather than considering that money laundering is not overrepresented in these assets.

As for the IMF, it’s no better: the latest report on public policies related to crypto-assets (September 2023)27 points out the lack of data on money laundering and terrorism financing risks, stating that “such impacts have not been specifically studied in relation to crypto-assets.”

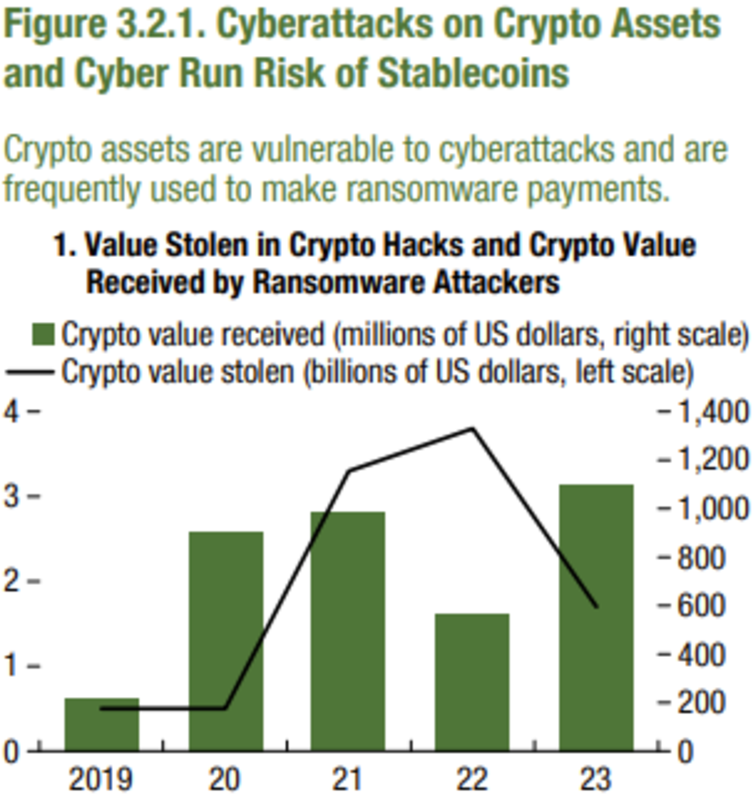

The IMF’s Global Financial Stability Report for 202428 relies on Chainalysis figures and proposes the figure of $1.1 billion received in cryptocurrencies for ransomware globally, which is less than 0.07% of the crypto market capitalization.

The IMF’s twin institution, the World Bank, does not significantly differ from the aforementioned views. In a 2023 report the institution indicates that the issue of “Virtual Assets” was not addressed in the Risk Assessment and calls on public authorities and companies to provide more data regarding these assets.

In its money laundering-related publications for 202030 and 202231 the World Bank simply makes no mention of cryptocurrencies. In its articles32 33 on crypto adoption, the World Bank merely sidesteps the issue by redirecting to FATF papers.

We have come full circle: reports cite each other, asking for more clarity on the figures, but nobody ever conducts the study itself. We rely on FATF, an unelected body, not subject to the rules of a respectable democracy, especially regarding proportionality, as I mentioned earlier.

The objective is no longer to allow a proportionate fight against money laundering but to raise the standards of controls every year, forgetting the reason why these controls were implemented in the first place.

Moreover, financial institutions use the term “compliance” to emphasize the fact that they comply with the expected control standards. The objectives of efficiency and proportionality are no longer at stake. There is no doubt that if FATF recommended putting a policeman behind every computer, legislators would rush to transpose this “best practice” into law…

It’s not even hidden. In the regulation voted on April 24 by the European Union34, the justification for imposing new standards on crypto companies is absolutely not focused on combating money laundering and its effectiveness. Indeed, since MiCA has not even entered into force yet, and the adaptation of the TFR text to cryptos is very recent, how could we conduct a posteriori analysis of the effectiveness of measures that have not yet had an effect and possibly judge that they need to be strengthened?

The reasoning behind the strengthening of controls is in fact much simpler: “Due to rapid technological developments and the advancement in FATF standards, it is necessary to review that approach.”

It is not the evolution of the threat, its assessment, the means used by criminals, or the results of a study, etc., but rather the advancement in FATF standards that leads Europe to align itself.

And the next steps are already laid out: “At the same time, advances in innovation, such as the development of the metaverse, provide new avenues for the perpetration of crimes and for the laundering of their proceeds.”

While the most popular metaverses are still in the experimental stage and barely see a few hundred people connecting simultaneously, and as the hype subsides, they are already being talked about as nothing less than “avenues” for money laundering.

If you’re looking for numbers and analyses, look elsewhere. The imposition of additional surveillance standards relies more on beliefs and perceptions than on facts because no one dares to oppose as a policymaker, risking being equated with a supporter of terrorism or money laundering. It’s therefore a genuine religion, one that becomes almost impossible to question at its core.

The digital transition has been greatly beneficial for states: with the need to be banked to take advantage of financial globalization, leading to the omnipresence of banks, the number of potential targets to monitor has drastically diminished, until it ended up concerning only a handful of banks. The transition from a world in which everyone held their cash at home to one where, at least in the OECD, banking is the norm, entails an inevitable financial intermediation.

In this regard, Bitcoin was a huge wake-up call because it signifies that the entire financial regulation of the past 30 years is obsolete, as it is based on an assumption that is no longer valid, namely the need for a financial intermediary to conduct transactions in the digital world.

In tomorrow’s world where companies will make wallet-to-wallet payments, who will perform KYC? Will we only realize the absurdity of the model when half the planet is working to monitor the other half?

Bitcoin shakes the very foundations of anti-money laundering efforts. And rather than questioning the regulation and its relevance, both in terms of effectiveness and in terms of respect for fundamental freedoms, we prefer the path of blindness, which leads to restricting the use of a technologically neutral tool by arbitrarily impeding innovation, the right to property, and the protection of exchange confidentiality, the importance of which for democracy, notably through encryption of exchanges, has recently been reaffirmed by the European Court of Human Rights35.

Bitcoin is a canary in the mine. A signal that something is slipping away from us, not concerning cryptocurrencies, but concerning the fundamental freedoms of all citizens, threatened by financial surveillance.

[1] https://uitspraken.rechtspraak.nl/details?id=ECLI:NL:RBOBR:2024:2069

[2] Phil Zimmermann, Why I Wrote PGP, https://www.philzimmermann.com/EN/essays/WhyIWrotePGP.html

[3] François Sureau also alerted us in this regard: “This adds nothing to the fight against terrorism. On the contrary, it gives him a victory without a fight, by showing how fragile our principles were. François Sureau, Pour la liberté — Répondre au terrorisme sans perdre la raison, Tallandier, Essais, 2017, p.11.

[4] This tends to prove Satoshi Nakamoto right, who wrote on bitcointalk on December 11, 2010, “WikiLeaks has kicked the hornet’s nest, and the swarm is headed towards us.”. He discusses the sudden attention Bitcoin is receiving following Wikileaks’ announcement that they would accept bitcoin donations. For Satoshi, this attention became a danger, and this message will be one of his last before disappearing and preserving his anonymity.

[5] US Attorney’s Office Southern District of New York, Founders And CEO Of Cryptocurrency Mixing Service Arrested And Charged With Money Laundering And Unlicensed Money Transmitting Offenses, 2024 https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdny/pr/founders-and-ceo-cryptocurrency-mixing-service-arrested-and-charged-money-laundering

[6] FBI, Alert on Cryptocurrency Money Services Businesses, 2024, https://www.ic3.gov/Media/Y2024/PSA240425

[7] Voir par ex. Florent Latrive, Téléchargement : les logiciels P2P menacés d’interdiction, 3 mai 2006, https://www.liberation.fr/futurs/2006/05/03/telechargement-les-logiciels-p2p-menaces-d-interdiction_37994/ ; Estelle Dumout, Vers une interdiction des logiciels peer-to-peer n’intégrant pas de DRM ?, 1 novembre 2005, https://www.zdnet.fr/actualites/vers-une-interdiction-des-logiciels-peer-to-peer-n-integrant-pas-de-drm-39286440.htm.

[8] Voir par ex. The Kazaa Ruling: What It Means, 2 avril 2002, https://www.wired.com/2002/04/the-kazaa-ruling-what-it-means/ ; Christophe Guillemin, La Cour de cassation néerlandaise confirme la légalité de Kazaa, 22 déc. 2003, https://www.zdnet.fr/actualites/la-cour-de-cassation-neerlandaise-confirme-la-legalite-de-kazaa-39134304.htm.

[9] Gérard Glaise, La responsabilité des distributeurs de logiciels de peer-to-peer : l’exemple du canari dans la mine?, 14 oct. 2004, https://www.droit-technologie.org/actualites/la-responsabilite-des-distributeurs-de-logiciels-de-peer-to-peer-lexemple-du-canari-dans-la-mine/.

[10] Lionel Thoumyre, Peer-to-peer : un « audiopathe » partageur relaxé pour bonne foi, 17 juillet 2006, https://www.juriscom.net/wp-content/documents/da20060717.pdf.

[11] Madison Park, 90 percent of U.S. bills carry traces of cocaine, https://edition.cnn.com/2009/HEALTH/08/14/cocaine.traces.money/

[12] Damian Williams, The Government’s Opposition To Defendant Roman Storm’s Pretrial Motions, 2024, https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.nysd.604938/gov.uscourts.nysd.604938.53.0.pdf

[13] FinCen, Application of FinCEN’s Regulations to Virtual Currency Software Development and Certain Investment Activity, 2014, https://www.fincen.gov/resources/statutes-regulations/administrative-rulings/application-fincens-regulations-virtual

[14] FinCen, Application of FinCEN’s Regulations to Certain Business Models Involving Convertible Virtual Currencies, 2019, https://www.fincen.gov/sites/default/files/2019-05/FinCEN%20Guidance%20CVC%20FINAL%20508.pdf

[15] Directive 2018/1972 établissant le Code des communications électroniques européen, art. 2.

[16] Cour de Justice de l’Union européenne, Communiqué de presse n° 126/11, 24 nov. 2011, à propos de l’affaire Scarlet Extended SA, https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2011-11/cp110126fr.pdf.

[17] https://twitter.com/LynAldenContact/status/1784304037430456383

[18] Anti-Money Laundering Regulation EU, 2024, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2024-0365_EN.pdf

[19] Jeremy McBride, , « Proportionality and the European Convention on Human Rights », in The principle of Proportionality in the Laws of Europe, éd. Evelyn Ellis, Hart Publishing, 1999, p. 25 ; Cour EDH. Hertel c. Suisse, 25 août1998, §50, https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/?i=001-62778.

[20] https://twitter.com/StachAlex/status/1776914160355303883

[21] Groupe de travail « Article 29 », avis 01/2014, n°3.26 (et jurisprudence citée).

[22] Cour EDH, X. et Y v. Pays Bas, 26 mars 1985, https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/?i=001-62162.

[23] Joint Opinion of the European Supervisory Authorities on the risks of money laundering and terrorist financing affecting the European Union’s financial sector, 2019, https://register.eiopa.europa.eu/Publications/Joint%20Opinion%20on%20the%20risks%20on%20ML%20and%20TF%20affecting%20the%20EUs%20financial%20sector.pdf

[24] EBA Opinion on ‘virtual currencies’, 2014, https://extranet.eba.europa.eu/sites/default/documents/files/documents/10180/657547/81409b94-4222-45d7-ba3b-7deb5863ab57/EBA-Op-2014-08%20Opinion%20on%20Virtual%20Currencies.pdf?retry=1

[25] Federal Department of Justice and Police of Switzerland, National Risk Assessment (NRA):Risk of money laundering and terrorist financing posed by crypto assets and crowdfunding, 2018, https://www.sif.admin.ch/dam/sif/en/dokumente/Integrit%C3%A4t%20des%20Finanzplatzes/nra-bericht-krypto-assets-und-crowdfunding.pdf.download.pdf/BC-BEKGGT-d.pdf

[26] Federal Department of Justice and Police of Switzerland, National Risk Assessment (NRA) Risk of money laundering and the financing of terrorism through crypto assets, 2024, https://www.newsd.admin.ch/newsd/message/attachments/86329.pdf

[27] Lola Leetz, EU Parliament Adopts AML Laws Regulating Bitcoin Based on Questionable Assumptions, 2024 https://bitcoinmagazine.com/legal/eu-parliament-adopts-aml-laws-regulating-bitcoin-based-on-questionable-assumptions

[28] Council of Europe, Annual Report 2021 MoneyVal, https://rm.coe.int/0900001680aad1fc

[29] Council of Europe, Money Laundering And Terrorist Financing Risks In The World of Virtual Assets, 2023, https://rm.coe.int/0900001680abdec4

[30] Financial Stability Board, MF-FSB Synthesis Paper: Policies for Crypto-Assets, 2023 https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/R070923-1.pdf

[31] FMI, Global Financial Stability Report, The Last Mile : Financial Vulnerabilities and Risks, 2024, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/GFSR/Issues/2024/04/16/global-financial-stability-report-april-2024

[32] World Bank Group, Lessons Learned from the First Generation of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Risk Assessments, 2023, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/2e1f3f32-57ad-43cb-bb8e-d1aab5636be4/content

[33] World Bank Group, Matthew Collin, Illicit Financial Flows: Concepts, Measurement, and Evidence, 2019, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/d2f7fa07-a285-5c5b-880e-25002a4951fb/content

[34] World Bank Group, National Assessments of Money Laundering Risks: Learning from Eight Advanced Countries’ NRAs, 2022, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/b860c956-659e-5005-93c9-4f06993c37ab/content

[35] World Bank Group, Crypto-Assets Activity around the World Evolution and Macro-Financial Drivers, 2022, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/738261646750320554/pdf/Crypto-Assets-Activity-around-the-World-Evolution-and-Macro-Financial-Drivers.pdf

Source link

Taliban jailed 8 traders for holding and using crypto

Solana Struggles to Rise Amid Bitcoin Price Uncertainty

Developing in Web 3.0 Is on the Cusp of a Breakthrough

Digital Shovel Sues RK Mission Critical for Patent Infringement on Bitcoin Mining Containers

crypto will get positive regulation ‘no matter who wins’ election

Toncoin (TON) v Cardano (ADA): On-chain Data Show Gains

Crypto Markets Like Their Odds With Kamala Harris

How Financial Surveillance Threatens Our Democracies: Part 2

CleanSpark’s amped hashrate mined 445 Bitcoin in June

Ripple and Coinbase Use Binance Win to Contest SEC Claims

DCG, Top Executives Renew Push to Get New York AG’s Civil Fraud Suit Dropped

Introducing Satoshi Summer Camp: A Bitcoin Adventure for Families

US judge approves expedited schedule for Consensys suit against SEC

2 Cryptocurrencies To Buy Boosting Into Top 10

Bitcoin Miners Slow Down Selling In July, What This Could Mean For Price

Bitcoin Dropped Below 2017 All-Time-High but Could Sellers be Getting Exhausted? – Blockchain News, Opinion, TV and Jobs

What does the Coinbase Premium Gap Tell us about Investor Activity? – Blockchain News, Opinion, TV and Jobs

BNM DAO Token Airdrop

NFT Sector Keeps Developing – Number of Unique Ethereum NFT Traders Surged 276% in 2022 – Blockchain News, Opinion, TV and Jobs

A String of 200 ‘Sleeping Bitcoins’ From 2010 Worth $4.27 Million Moved on Friday

New Minting Services

Block News Media Live Stream

SEC’s Chairman Gensler Takes Aggressive Stance on Tokens – Blockchain News, Opinion, TV and Jobs

Friends or Enemies? – Blockchain News, Opinion, TV and Jobs

Enjoy frictionless crypto purchases with Apple Pay and Google Pay | by Jim | @blockchain | Jun, 2022

How Web3 can prevent Hollywood strikes

Block News Media Live Stream

Block News Media Live Stream

XRP Explodes With 1,300% Surge In Trading Volume As crypto Exchanges Jump On Board

Block News Media Live Stream

Trending

Altcoins2 years ago

Altcoins2 years agoBitcoin Dropped Below 2017 All-Time-High but Could Sellers be Getting Exhausted? – Blockchain News, Opinion, TV and Jobs

Binance2 years ago

Binance2 years agoWhat does the Coinbase Premium Gap Tell us about Investor Activity? – Blockchain News, Opinion, TV and Jobs

- Uncategorized3 years ago

BNM DAO Token Airdrop

BTC1 year ago

BTC1 year agoNFT Sector Keeps Developing – Number of Unique Ethereum NFT Traders Surged 276% in 2022 – Blockchain News, Opinion, TV and Jobs

Bitcoin miners2 years ago

Bitcoin miners2 years agoA String of 200 ‘Sleeping Bitcoins’ From 2010 Worth $4.27 Million Moved on Friday

- Uncategorized3 years ago

New Minting Services

Video2 years ago

Video2 years agoBlock News Media Live Stream

Bitcoin1 year ago

Bitcoin1 year agoSEC’s Chairman Gensler Takes Aggressive Stance on Tokens – Blockchain News, Opinion, TV and Jobs